As the polls closed on 5 May 2005, the then little-known MP for Islington North must have felt certain of success. Not only did Jeremy Corbyn enjoy a plump majority, but he also held the honour of being the Labour Party’s most disloyal MP, having defied Tony Blair’s increasingly unpopular leadership on issues ranging from the Iraq War to university tuition fees.

His constituents, however, had different ideas. That year, Corbyn’s share of the vote fell 10.7 percentage points; a far worse showing than in London as a whole, where the Labour vote fell by only 7.9 percentage points.

However much it might bruise parliamentary egos to admit it, the simple truth of British general elections is that voters have never cared a great deal about the voting records of their MPs. A raft of statistical studies on the subject has repeatedly produced results showing that—even on issues as divisive as the Iraq War—MPs’ voting records have a negligible influence on their electoral fortunes.

But MP’s fantasies die hard, and dreams of constituents throwing admiring glances across the dinner table at the family portrait of their elected parliamentarian have generally proved more appealing than the tale of indifference told by the statisticians.

For those of us with a favourite Excel command, therefore, Theresa May’s snap election was a cause for jubilation. Here was an election that not only came immediately after the EU Referendum—an event that allowed voters across the country to discover whether their MP agreed with them on a binary and highly divisive issue—but which the Prime Minister explicitly framed as a vote on the issue of Brexit. Surely, if voters had even the slightest inclination to see MPs as anything more than a helpful spot to display rosettes, this was going to be the time to show it.

In Westminster, meanwhile, the idea that MPs would be punished at the ballot box for campaigning on a different side of the Referendum to their constituents seemed so obvious that few stopped to even question it. Lib Dems promptly poured resources into Remain supporting Vauxhall with the hope of ousting Brexiteer Kate Hoey, while Open Britain compiled an ‘attack list’ of Remain supporting seats with Leave supporting MPs.

So, who called it right, the spads or the stats nerds? The first thing to say is that this most certainly was a Brexit election, and while the Tory campaign may have gone down in flames, its belief that Leave supporting areas offered fertile ground for the Conservative message were not unjustified.

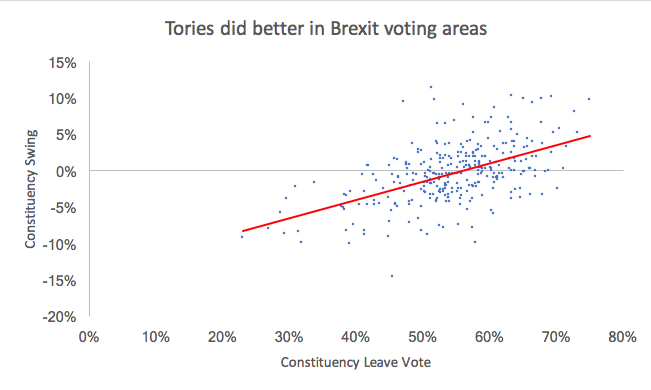

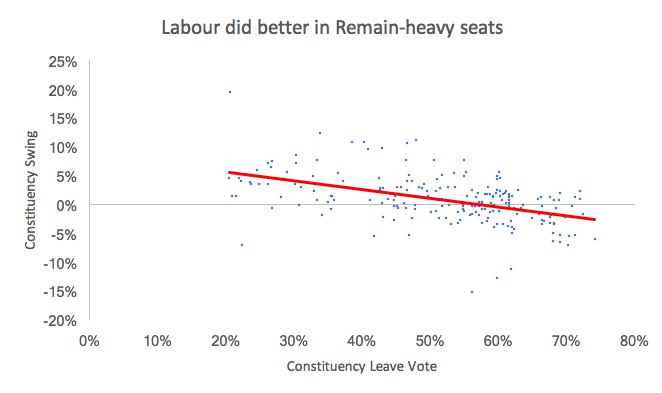

Showing this is pretty straightforward and on the graph below (yes, I know, I’m sorry) I’ve plotted constituency swing[1] against the percentage of voters in the constituency who voted Leave in 2016.

While the data is fairly noisy, the trend is pretty clear in showing that Tory MPs faired substantially better in Brexit supporting areas. In fact, a simple regression shows that for every 4 percentage-points more Leave voting an area was, Conservative MPs could expect to benefit from a 1 percentage-point bounce. As you might expect, the Labour vote shows the opposite trend, with MPs performing better in Remain-heavy constituencies; although for Labour the trend was less pronounced with candidates enjoying a 1 point bump only for every 6.5 percentage-point increase in remain voters.

So far so predictable, but just because voters were paying attention to Theresa May smack-talking Jean-Claude Juncker doesn’t mean they cared, or noticed, whether their MP was a Brexiteer.

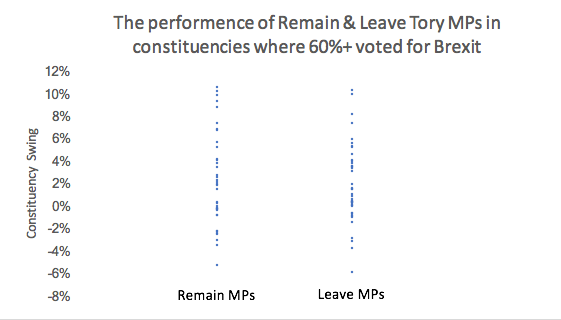

Getting to the bottom of this is a slightly trickier process because MPs’ decisions to back Remain or Leave are not independent from how Remain-or Leave-supporting their constituency is. In fact, after quickly crunching the numbers, I found that the more Leave supporting a Tory MP’s constituency was, the more likely they were to back Leave themselves (too few Labour MPs backed Leave for the same analysis to be done with Labour).

This poses a bit of a problem as it makes it hard to distinguish whether Tory MPs who backed the Referendum position favoured by their constituents did better because it gave them a personal vote, or because they tended to be in Brexit-voting areas where the Tories performed better anyway. The way to get around this is to break seats up into three chunks: those where less than 50 per cent of constituents voted leave, those where 50-60 per cent voted leave and those where more than 60 per cent voted leave. When you run the figures for these three groups separately the results are pretty clear: 2017 saw no discernible correlation between an MP’s performance at the ballot box and the campaign they supported at the Referendum.[2]

This might all seem a bit abstract, but it has real implications that professional campaigners still don’t seem to have learned.

In the case of the Lib Dems in Vauxhall, for instance, real money was spent on the basis that voters would suddenly start making up their minds based on factors that had never influenced them in the past; not generally a great strategy for allocating your resources. As the unlikely march of the soft-Brexiteers picks up pace following the election, meanwhile, Europhilic MPs should feel emboldened by how little their constituents seem to care about their voting records.

To a lot of people this result may seem very unintuitive. As I mentioned at the start of this article, however, it shouldn’t really be a surprise. Not only has there been plenty of evidence in the past that personal votes are pretty negligible in British politics, but it’s also worth remembering that only about 22 per cent of people can actually name their MP, let alone tell you whether they were a Brexiteer.To be absolutely clear, this doesn’t mean that there weren’t Remain MPs in Leave voting constituencies that severely underperformed. There most certainly were. What it means is that there were just as many Leave MPs that underperformed just as much.

The truth, of course, is that, like any object of extraordinary size, Westminster’s collective ego is likely to go on pulling unwitting columnists and campaigners into its orbit on this issue for the foreseeable future. However, it’s nice to know that at least one outcome of Brexit, however trivial, can be chalked up as a win for the experts.

Many thanks to the folks at Britain Elects for putting up the results data so quickly, and to Chris Hanretty for his excellent estimates of constituency-level Referendum results. ***

[1] Actually, what I’ve technically used is not swing, but something I call ‘adjusted gains’. This is basically how well a party have done in a particular constituency relative to how the party did in that county (the idea being that this adjusts for the fact that, for instance, a Tory maintaining their 2015 vote share would be a good result in London, but an underperformance in South Yorkshire, where the party made big gains).

[2] For those of you interested in the details of how I did this, all I did was run a simple linear regression for the three groups of seats using the ‘adjusted gains’ score as my dependent variable and a dummy variable denoting which side of the referendum an MP supported as my independent variable. The p-values for the constituency groups where Leave voters made up 50 per cent -, 50-60 per cent, and 60 per cent+ of constituents were 0.29, 0.19, and 0.63 respectively.