Going into the election most commentators expected Labour to lose ground. However, the party’s strong performance saw it picking up 30 seats and increasing its majorities across a raft of previously marginal constituencies.

When looking at the reasons for this better-than-expected performance, many have pointed to Jeremy Corbyn’s ability to motivate young people to turn out and vote for his party. But how far does the perception that it was the young that swung things tally with the reality?

Our post-election survey of more than 52,000 people found that turnout among 18-24 year-olds was 58 per cent—11 points lower than the overall rate. But older people are still much more likely to vote than younger people, with turnout among those aged 70+ hitting 84 per cent. However, while the youth is being comprehensively out-gunned by the baby boomers, there are a couple of important points to make.

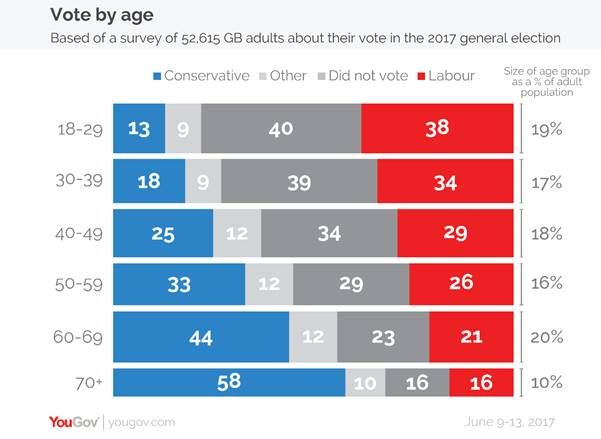

The first is that age is an important indicator as to how someone will vote as well as whether they will vote. The chart below combines these two issues. The youngest parts of the British electorate, 18-24 year olds, are three times as likely to vote Labour as they are Conservative. However, despite this advantage, more under-25s chose not to vote than voted for Labour (something that is actually true for the party among all age ranges).

The second is about the concentration of votes. In certain seats—most noticeably university constituencies such as Canterbury, Sheffield Hallam, and Cambridge—it seems as though the votes of 18-24 year-olds were highly concentrated and highly effective at either delivering the seats to Labour or dramatically boosting its vote share (the party’s majority in Cambridge went from 599 in 2015 to 12,661 last week).

However, given Labour increased its national vote share by nine points, it would be wrong to say that it was young people alone that helped it improve its position. Because there are more older people and they are also more likely to turn out, Labour was in fact more reliant on voters over the age of 40 than under it. More than half (54 per cent) of those who voted for the party at the election were aged 40 or older, compared to 46 per cent who were 39 or younger (including the 26 per cent who were under 30).

But beyond age, there was another clear factor at play in Labour’s support: education. Our research found that the higher the educational qualification a person attained, the more likely they were to vote Labour. Almost half (49 per cent) of people with degree-level qualifications or above opted for Labour compared to 33 per cent of those with no higher qualification than GCSEs.

While this is to a certain extent a factor of age—young people are more likely to have a degree—even accounting for this the Conservatives still seem to have a “graduate problem.” This is also important because turnout is higher amongst more educated groups (eg 79 per cent amongst those with a degree or above) than amongst less educated groups (eg 60 per cent amongst those with GCSEs or lower).

So although people are right to think that Labour has benefitted handsomely from the votes of younger people, the party may be reaching the limits of what it can achieve on the back of Britain’s youth. This is especially true given Labour’s young voters are flakier—less likely to stick with the party and less likely to vote in general—than Conservative voters are. In order to push the party into majority territory it will have to start tapping into the richer seam of older voters.