Ellen Halliday, deputy editor: Immigration is one of the biggest political issues of our time—and one policy that’s been proposed as a potential solution is the introduction of national identity cards. Under the proposal being put forward by the thinktank Labour Together, these cards would be mandatory, free of charge and digital, largely downloaded onto people’s smartphones. This isn’t the first time that we’ve had a discussion in the UK about ID cards—David, could you put forward the best argument you can about why ID cards might now be a good idea for Britain?

David Blunkett, Labour peer and former home secretary: Well, firstly, could I unravel or unpack the immigration issue from the wider issue? I always believed, when we started this debate over 20 years ago, that owning your identity—being able to verify and present your identity—was really crucial. That was right at the beginning of the development of smartphones and the kind of technology and data drawdown that we have today. But it also had an implication in terms of what we were doing on immigration.

The French always said: “Look, the quid pro quo for us taking action at our end [to stop people crossing the Channel] and doing what we do is that you have a clue who is entitled to work, who is entitled to free public services (because we have free public services: the NHS and education are obvious ones) and [about] the crucial area of enforcement.” You can’t enforce employment rights, and you can’t enforce the right to take action against employers if you can’t verify somebody’s identity. That all got morphed up together into a debate about the surveillance state. And I have to admit that if I was back in time—if I was doing this again—I’d have simply tagged [identity cards] to passports.

The problem with the Labour Together proposal about making it free is that we have to pay for passports. Somebody has to pay for processing our data, verifying that we are who we say we are, and giving us the right to travel. If we could build on that, I think we could take some of the steam out of it.

Now, I’ve always accepted that there’s a secondary issue, in terms of avoiding a surveillance state and therefore whether we are intruding on people’s civil liberties. It is secondary only because if you had a surveillance state, they’d have identity cards and an identity system whether you liked it or not.

So we’re talking about a democracy where we should try and agree to do this based on the fact that we’ve moved into an entirely new world with smartphones, with the drawdown of data of all sorts, and with people having to prove their identity every day, including for being able to use your bank.

Ellen: Surveillance is obviously one of your key concerns at Big Brother Watch. We’re living in a different world now in terms of surveillance compared with when David first talked about introducing national ID cards 20 years ago. Can you explain why Big Brother Watch thinks that ID cards would not be the right thing for Britain?

Rebecca Vincent, interim director of the civil liberties group Big Brother Watch: Firstly, I think it’s very helpful that David has disentangled immigration from the question of this digital ID, because to us this isn’t about immigration at all. That’s the current political debate but, as has been mentioned, there’s been a long history of other proposals, first for national ID cards and now for this digital form of ID.

It’s maybe more accurate to think of it not only as an ID, but as our data. And this is really about the government wanting access to, and control of, all of our data.

At present, one of the big problems that’s trying to be addressed is illegal immigration. But we don’t think that violating the privacy rights of tens of millions of people is the way to do it. We don’t see how the current proposal by Labour Together would accomplish its flimsy promises on immigration, or these other areas of societal concern. It’s not a panacea.

From a civil liberties perspective, what would happen is a fundamental reversal for people—and I don’t want to say just citizens, because this will impact residents as well as citizens in the UK. It would upend our relationship with the state, turning us into a “papers, please” society. It would put the burden on tens of millions of innocent people who are law abiding, who are doing what they’re supposed to and have other means of proving who they are, when necessary, in this attempt for this current government to look like it’s doing something about immigration.

David: Perhaps we could just see what Rebecca would agree to, because over three-quarters of us have passports and a very large number have driving licences. Fairly obviously, for one very good reason, I don’t have a driving licence, but they are going to be digitiised. The DVLA is moving to this later in the year. The NHS has got a system running already and it’s going to update that in terms of your identity and presentation on a smartphone. And there’s already a unique pupil identifier for youngsters in school, for fairly obvious reasons.

The government is calling its digital part of all this “the wallet”. Now, I’m not a great techie person, so I’m not clear how this “wallet” would work other than that it endeavours to pull together different strands of data. The minute you do that, you’ve got a system but without the safeguard. So what I want is for them to move towards what they’re doing, but to actually do it openly and transparently—which I think, Rebecca, you would like—and to put in safeguards against the kind of things that you are worried about.

Rebecca: For us, the red line here is the question of mandatory and universal digital ID. We are indeed living in a digital world. At Big Brother Watch we’re not opposed to technology; we’re not opposed to the use of digital tools when they can better our lives. But there always have to be other options.

We would take serious concern if there was a proposal that the state would force us to have one specific thing to access basic services. It would be perhaps a different story if there was a new tool offered to those who might choose to use it. But when it becomes mandatory, that’s a real concern for us.

We don’t believe there are sufficient safeguards in what is currently on the table to get what we would need to feel comfortable about it from a civil liberties perspective, or indeed a digital security perspective.

We have concerns about creating this massive, centralised database of all of our information, including possibly now biometrics, without a guarantee that criminal elements, foreign adversaries or other malicious actors also couldn’t gain access to it. So there’s a number of concerns, ranging from the philosophical, ideological underpinnings here to the practical, digital security aspects.

David: If I was back in time, I’d have simply tagged identity cards to passports

David: Protecting the system is important. We can agree on that—that actually we do need to look at how you have firewalls, how you protect the system from intrusion and abuse. It’s always been a problem.

The recently deceased Frederick Forsyth, author of a number of famous books including The Day of the Jackal, and I both had our data, our personal space intruded on with an experiment a few years ago by the BBC. They wanted to see how easy it was to get a driving licence in someone else’s name and be able to use it. But I can’t drive. [Forsyth was chosen because, in The Day of the Jackal, an assassin steals people’s identities.]

He was a very talented, but far-right, individual who was worried about what they’d done; I was, from the left, worried about the way in which I couldn’t protect my identity. So I’ve been interested in both sides of this.

How do we do it? Because it’s happening. It’s not going to stop it, it’s happening. How do we do it in a way that would satisfy you, Rebecca?

Rebecca: I think there are ways to support digital inclusion that don’t represent a massive privacy rights violation for the entire population.

Digital inclusion also means providing for those who cannot or won’t be online, because those people will always exist. And this includes some of the most vulnerable of our society. It includes those who don’t have high digital literacy rates. It includes those in conditions of poverty, the disabled, the elderly, and legal communities of migrants as well. There also will always be people who so fiercely guard their privacy rights that they don’t want to have a smartphone, even if they could afford one. There are many people who don’t have one at present. There aren’t sufficient provisions for how these people would be supported if we’re all suddenly supposed to have this mandatory digital ID in the form of an app on our phone. That’s really concerning.

It’s always that question of being forced and not having other options.

David: I’ve got a smartphone that I find impossible to use because, as I’ve already confessed, I’m not very techie. I’d like a card like a modern credit card, where you could use it under £100 to pay a bill. So I could swipe it if I needed to. Now, we’d probably need safeguards on that as well, because if somebody stole it, then of course they could use it. So I’d be in favour of some other backup, like a thumbprint, which is pretty secure. If we could have a card for those of us who don’t want to do the smartphone, would you still oppose that?

Rebecca: We would still oppose it if it were mandatory. Because we have many options at present to be able to prove things, if we need to. And if there are categories of people who cannot access these existing means of proving one’s identity or address, or other things that might be needed to participate in society, we could look at those as specific individual solutions, but not forcing tens of millions of people to have the so-called BritCard, in the name of rooting out illegal immigration and other societal problems.

David: I’d like to start with where we’re at and with what’s happening around us. Three-quarters of the population plus hold a passport and so are already in some way doing this. We have to think about how it could be coordinated and protected.

If we started with a system that was voluntary, we’d have to be careful. If you were saying that access to employment, to free services, to whatever, was dependent on you being able to present or verify your identity, and you weren’t part of this voluntary scheme, you’d have to have another way of confirming your identity. Now, if there wasn’t another way, you’d effectively be forcing people into the system anyway, wouldn’t you?

Ellen: Can we perhaps talk about what a compulsory ID would mean for someone? If there was a mandatory scheme, how would it impact our lives? How would we use it, and when would we be asked to present it?

David: Well, at its best it would mean you didn’t have to have multiple ways of demonstrating your identity. Rebecca’s right: we do have multiple ways. But it’s a mess. If you need different systems, different approaches, different data presentation for different purposes, it’s messy for people and the government.

Not just this government, but previous governments have tussled with this in terms of access to government and local government services—to try and make it easier for people. How can you do that while still giving people choice? I don’t have a very clever answer, but I think it’s doable.

Rebecca: All of us could end up on a national facial recognition watchlist, which is fairly dystopian

Ellen: So is there an argument that it actually reduces the hurdles that people have to get over to access services?

Rebecca: Well, what I would say is this proposal, as it stands, would require these checks for things like accommodation, for employment. Actually, many of these checks are already required. Employers have been required in this country since the 1990s to verify identity before employing people. We would suggest this would add to the mess, in fact, because it would put an additional burden on those, which is the vast majority of us, who are already abiding by the law to go through this extra set of checks. If we look at the government’s other attempts to streamline things in such a way, such as the e-visa system, it is riddled with system failures and inaccuracies, and we don’t see how this would be any different.

So I’m afraid the idealised version might seem that things could be streamlined and easier, but in practice, with what we’ve seen from government, I’m afraid that it would contribute further to the mess.

I also wanted to pick something back up. You mentioned fingerprints earlier, David, so we’ve gotten into the territory of biometrics.

This proposal isn’t occurring in a vacuum. When we look at the broader situation concerning surveillance and the threats to privacy rights in this country, we have a proliferation of attempts by authorities to get at our biometrics in different ways.

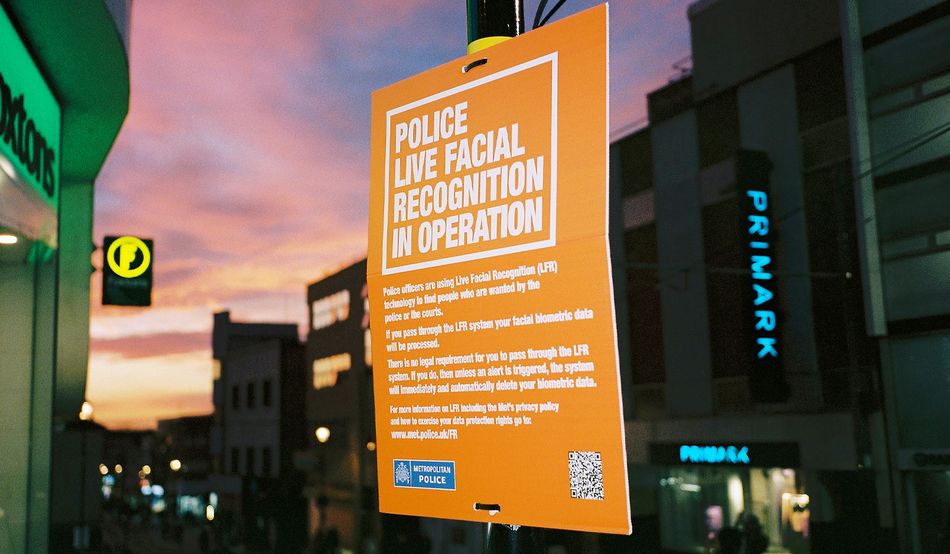

At Big Brother Watch, we work a lot on the issue of live facial recognition technology, which has been proliferating across the UK, both by police and the private sector, all with no legislative basis.

We now have a provision in the new crime and policing bill that is attempting to bring the DVLA’s database into these watchlists, which then could be used for live facial recognition purposes. So it’s very concerning now to think of all of this being even more centralised. Perhaps it would all then be joined up, if it is efficient in the way that government hopes it would be. And perhaps all of us then end up on this sort of national facial recognition watchlist, which is fairly dystopian and not a society we want to live in.

David: Let me just pick up the last point first. Car registration is already on the national system. They can pick your car registration up, unless you’re forging it, wherever you are. And that’s been in place for a long time.

On the issue that you raised earlier about employers, I think most employers find it cumbersome at the moment. It’s quite a burden to go through. You can’t say to somebody, “Look, your accent or the colour of your skin or how you look makes me suspicious about you, so I’m going to make you jump through hoops that I don’t make everybody else [jump through].” Whereas, if you’ve got a very clear system that’s verifiable and reliable, then it makes it easier for them.

When I was on the justice and home affairs committee in the House of Lords, we did an inquiry on facial recognition, and we recognised that we needed proper rules. At the moment, police services, particularly in London and Northamptonshire and south Wales, are doing things that don’t necessarily have ethics behind them, and we wanted to do that. So actually we’ve reached some agreement, Rebecca. Because I think without that, there is a real danger, and people do deserve to know what’s going on and for it to be transparent and clear as to when facial recognition is used, why it’s used, how the information is stored, and what’s done with it. I agree with that. So we can move a little bit towards each other, I think.

Rebecca: Certainly. But I guess if we go back to our initial question, we don’t really see how this mandatory, universal digital ID scheme would stop things like small boat crossings. That seems like quite a leap.

David: Well, it’s a leap only if you don’t actually link it to the way that the French will do more with us—as they did back in 2002, 2003, when I was there and managed to stop the original business model of getting people across—if you do something about the pull factors, about the incentives to come to the UK. There’s a kind of quid pro quo.

But actually also—and I think there is a good point here—if people are trafficked into the sub-economy, and they’re exploited, it’s modern slavery by any other name, because they’ve disappeared. A lot of people who think they’re not going to get asylum just disappear. And some people who have been refused asylum disappear. And the organised criminals get them.

The way to stop that is to have proper identification, and again it comes back to employers and enforcement. So that police and the people who are dealing with minimum wage inspections and things of that kind can then do it. It’s not a panacea, but it helps a bit.

Rebecca: In an idealised world, maybe. But in practice we fear that it will just be an additional burden on those who are already following the law. There will always be crime; there will always be attempts to disappear into the shadows, no matter what the innovations are.

From a civil liberties perspective, our fundamental right to privacy is so precious that it cannot be gambled with just to see if that might be the thing that sticks a little bit better than those that the government is currently trying.

Many of these issues, I think, would be better dealt with by properly resourcing authorities to do their jobs as it is. I’d say the same for facial recognition, too. Instead of always looking for some new announcement or some shiny new tool to employ, the government could actually resource our police properly to investigate and go after criminals, who we all know exist in many sectors of society.

David: Well, we’re both after an ideal world, I think. And you know, what we’re trying to do is to make sense of what’s happening now and to recognise that there are dangers. I’d be very foolish if I didn’t recognise the dangers of the system not working properly, of being intruded on or of fraud being committed. All those things are important, and we shouldn’t dismiss them.

By the way, I found myself a few years ago agreeing with Big Brother Watch, and I thought: am I becoming a liberal? What is happening to me? Most people get more rigidly conservative as they get older, but I seem to be going the other way.

Ellen: There is fairly broad support for some kind of national ID scheme, according to polling. YouGov has 24 per cent of people strongly supporting and 33 per cent tending to support some such scheme. More in Common finds 53 per cent are in favour. I’d love to hear from both of you how effective you think such a policy could be for a Labour government that is currently looking for popular policies.

David: Those polling figures are less impressive than when I was talking about it 20-odd years ago. So they’ve eroded a bit, even though people are downloading, using and presenting their data much more than they ever did in those days.

I’m in favour of the Labour government making very bold, clear policy statements about where they’re going and what they believe in. Neil Kinnock, the former leader of the Labour party, talks about the problem at the moment being an “audacity deficit”. He means that we’re cautious, ultra-cautious, that we’re tinkering rather than providing dramatic challenges to the status quo and arguing for what needs to be done.

That’s not easy, in the world we live in, and with the challenges the government faces, but I have sympathy for that argument because I think it’s the only way to see off the far right.

Rebecca: I don’t think this would be a good option for Labour. This country, which I have also legally immigrated to and made my life here as an adult …

David: Hooray!

Rebecca: And I’m glad to join many of the proud traditions of this country. The British people do have a strong history of rejecting proposals for mandatory ID—both the ID card form and now, I hope, the digital format.

We can nitpick the polling but I always see holes in the questions that are asked. It’s often not asked whether people would support mandatory ID, and that’s quite a different question than just the idea of a digital ID. Questions are often not asked about privacy rights or about which particular sectors of society the ID would be effective in. So if you isolate the immigration question, I suspect there would be more support for that than other areas of our life, where people think it would be more intrusive.

We are advocating for everyone’s rights. We’re now calling on the Starmer government to scrap this proposal. Something so fundamental should have been included in the Labour party manifesto if they were serious about this, and it’s very sneaky a year in to come up with such a radical change that would totally upend, again, the nature of our relationship with the state. This should have been put to the voters properly ahead of the general election.

I think that it is worth noting that the Home Affairs Committee of parliament has opened a consultation to look into this matter that closes, I believe, on the 21st of August. I would encourage everybody to put their views forward, because this needs proper scrutiny and a proper debate. And right now it’s only a very small portion of the parliamentary Labour party that has publicly supported this.

David: I would finish where I started, which is: all of this is happening around us ad hoc, without any kind of underpinning or overarching protection and coherence. For two reasons, the government should actually get a grip. One is the straight political one that if something’s going to happen, you might as well get some credit for it. And the second is that if we don’t, it’s just going to continue building but without the things that, Rebecca, you want. I think we should accept the inevitable and get a grip.

Rebecca: That’s a really good point to end on! ♦

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity