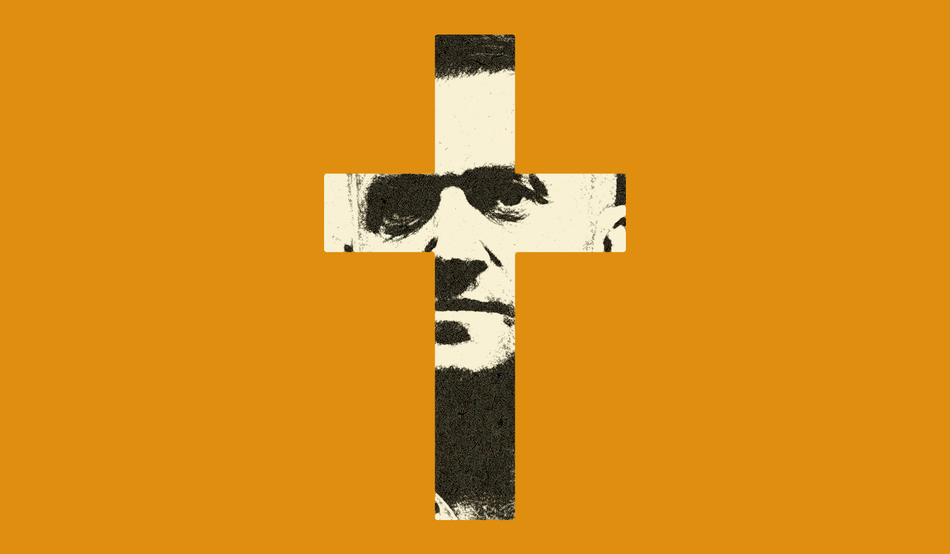

When Tommy Robinson walked out of prison on 27th May, his hair was unkempt and his beard was scraggly. The far-right activist, whose real name is Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, used his first speech since he was sent to prison seven months earlier to accuse the state of silencing him. In some ways, this was business as usual: presenting an image of martyrdom is central to Yaxley-Lennon’s brand. But what caught my eye was the Christian cross hanging on a rosary around his neck.

In response to the image, Daniel Thomas (known as “Danny Tommo”), often seen as Yaxley-Lennon’s right-hand man, tweeted in celebration: “this movement stands on Christ. Always has. Always will.”

Yaxley-Lennon and his allies have long framed Islam as a threat to “Judeo-Christian” culture, but recently they have more explicitly evoked Christianity. At rallies, a number of pastors have presented his movement as a crusade-like mission, saving Christianity from the imposition of Islamic extremism.

Most prominent is Calvin Robinson, a former GB News host who has been a priest in several denominations since the Church of England declined to ordain him as a minister. He was removed earlier this year from the Anglican Catholic Church after he mimicked Elon Musk by appearing to perform a Nazi salute at a pro-life conference.

Robinson frequently posts in support of Yaxley-Lennon on X, where he has over 400,000 followers. The two have hosted each other on their podcasts, discussing the perceived threat of demographic decline and claiming Islam is an “evil” in opposition to British and Christian values.

Both have held roles with the UK Independence Party (UKIP), as has Rikki Doolan, who says he is Yaxley-Lennon’s pastor and visited him in prison. During a call in early May, Doolan told me that Yaxley-Lennon first realised the power of putting Christianity at the centre of his movement when attending far-right rallies in Poland. For Doolan, the growing role of religion in the movement he identifies with is a sign of a Great British Christian revival. Under its current leadership, UKIP says it aims to put Christianity “back into the heart of government”.

Last month, Yaxley-Lennon said on American conservative Patrick Bet-David’s podcast that he used to not believe in Christianity despite being brought up by a Catholic mother, but that he has come closer to the religion because he thinks its decline has left a void in Britain and is the cause of the country’s decay. Yaxley-Lennon has said this was something he realised while reading the Bible in prison. “What built Great Britain?”, he asked rhetorically. “Christianity”.

According to Julia Ebner, an expert on the far right for the Institute of Strategic Dialogue, Yaxley-Lennon has been tailoring his rhetoric to appeal to followers in the United States, where many of his donations have come from in recent years.

In the US, the far right is rooted in Christian institutions, with Evangelical and Catholic leaders driving national debates around multiculturalism, sexuality and abortion. Yaxley-Lennon’s new proximity to religious figures indicates that he is bringing Christian nationalism across the Atlantic and into the British far right.

In the UK, crucial to this shift have been several pastors who are part of denominations outside of the mainstream Church of England. But Christian nationalism has also been on the rise inside the Church in recent years, Maria Power, a senior research fellow at Oxford University’s Faculty of Theology and Religion, told me. Evangelical and Anglo-Catholic sections of the church are forming alliances on issues such as migration and sexuality, creating tensions with the more liberal parts of the church.

“There isn’t a denomination in Britain that hasn’t been affected by the kind of Christian nationalist, right-winged extremist theology that’s developing,” said Power. “I think that [Yaxley-Lennon] is picking up on that, using it as a way to garner support and, in his own mind, as a way to make himself look respectable”.

Until now, Yaxley-Lennon’s focus on religion has been primarily centred on his belief that a growing Muslim population in the UK, just over 6 per cent of the population according to a 2021 national census, threatens Christianity. But there are signs his movement is also starting to engage with issues American evangelical groups have long been focusing on, relating to “traditional family values”.

From Oswald Mosley in the 1930s to the National Front in the 1970s and the British National Party in the early 2000s, far right figures and parties in Britain traditionally promoted themselves in purely racialised terms, pitting white communities against racial minorities, according to Joe Mulhall, director of research at the anti-racism organisation Hope Not Hate. Yaxley-Lennon’s movement, which Mulhall says came to prominence in the post September 11th era, has instead tried to present itself as more multi-racial, focusing its attention on the perceived threat posed by Islam. Christianity, says Mulhall, provides the far right with an opportunity to form a cohesive identity without referencing race.

Now Yaxley-Lennon joins a host of controversial figures with strong social media presences—like Russell Brand, who was baptised in the Thames last year—who in recent years have placed Christianity at the centre of their online identities.

There are a number of possible reasons for doing this. After facing several legal battles, Yaxley-Lennon and Brand may be trying to rehabilitate their images. But the answer may also lie in comments Yaxley-Lennon has made on several podcasts. Three weeks ago, he decried Christian leaders for making the Church “weak and pathetic”, claiming that it had been “infiltrated” and that it was now only known for “flying rainbow flags”. On Bet-David’s podcast, he said there was a need for “masculine Christianity” in Britain.

A YouGov survey released this year shows that the percentage of men aged 18 to 24 who attend church regularly has gone up from 4 per cent in 2018 to 21 per cent this year. Analysing similar trends in the US, political scientists Paul A Djupe and Brooklyn Walker have argued that young men are drawn to Christianity because it affirms traditional gender hierarchies.

Donald Trump and his vice president JD Vance also tapped into this sentiment during last year’s elections, speaking regularly on “manosphere” podcasts, at conferences and rallies about threats to both Christianity and masculinity and the role religious values should play in our lives.

Right wing movements in the US, Russia, Hungary and other European countries are increasingly focused on re-asserting the dominance of patriarchal conservative values, including expanding abortion limits.

Organisations such as the Alliance Defending Freedom, an American conservative Christian legal advocacy group, have started pushing some of these issues into the UK, for example, by providing legal representation to pro-life activists such as Adam Smith-Connor, who was convicted of breaching a safe zone after he prayed outside an abortion centre in Bournemouth.

Now Yaxley-Lennon and his allies are taking on the mantle. In April, Calvin Robinson said that “promoting the sanctity of life, protecting the vulnerable, is the most important issue of our time”. Just last month, when parliament voted to decriminalise abortions, Yaxley-Lennon accused MPs of “legalising murder”. Who can say whether he has had a genuine spiritual awakening, or whether he spies an opportunity to galvanise support amongst young men?

In September, Yaxley-Lennon will be holding a large rally, at which well-known American hard-right figures such as Steve Bannon are expected to attend. Do not be surprised to see some clerical collars poking out of the crowd. Or even preaching from the stage.