There is no evidence that the so-called “hostile environment” works even on its own terms. So Colin Yeo concludes in his excellent new book Welcome to Britain: Fixing Our Broken Immigration System. Given the amount of suffering caused by public bodies actively seeking out and making life intolerable for “illegal” (or undocumented) immigrants, under a policy that was created by David Cameron and Theresa May in 2012, this is a damning conclusion. Perhaps the time has finally come for politicians to pay attention. The publication of Yeo’s book seemed to be well timed: during the summer it appeared that ministers would finally be required to reflect on whether it is sustainable to maintain an immigration system constructed around cruelty.

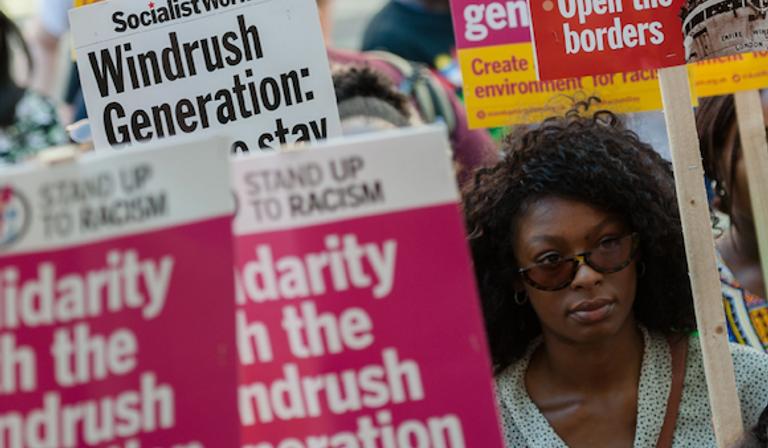

Four days before lockdown began in March, I went to what was to be my last press conference for months. Westminster already felt post-apocalyptic. A dozen reporters turned up for a briefing on the Wendy Williams review into what caused the Windrush debacle that saw long-term British residents thrown out of the country on flimsy pretexts. No one shook hands, and we backed away from each other nervously. But the review itself was powerful. Williams, a senior lawyer who has latterly worked in the inspectorate of the police, was tasked by a panicking government with carrying out a “lessons learned” report at the height of the Windrush scandal in 2018.

She made 30 hard-hitting recommendations for reform of the Home Office. Number seven called for officials to undertake “a full review and evaluation” of the hostile environment, assessing whether it is “effective and proportionate… given the risks inherent in the policy.” This evaluation must be done “scrupulously,” published in a “timely” manner and—because of the racially discriminatory nature of the policy—would have to take account of equality laws. The Williams review was met with benign platitudes by Home Secretary Priti Patel, who took the opportunity to apologise again to those wrongly classified as illegal immigrants. Then the global pandemic hit and the report was conveniently buried.

The recommendations appeared to have been forgotten until Windrush Day on 22nd June. Windrush Day was established after the scandal (with a token £500,000 of annual state funding granted as part of the government’s attempt to make amends) to celebrate the “outstanding and ongoing contribution” of those who migrated to the UK from 1948 onwards and their descendants. The Communities ministry had set up a day of Zoom meetings celebrating Caribbean cooking, music, dance, poetry and song—but this could not disguise the extreme difficulties those affected by the scandal still had getting compensation. By the end of June a total of £755,110 had been paid out to 110 people from a scheme expected to pay out anywhere between £200m and £500m.

In an apparent attempt to quell resurgent fury about the government’s behaviour, Patel made an appearance at the despatch box the following day, and unexpectedly announced she was accepting all 30 of Williams’s recommendations—committing her to a full review of the hostile environment, and also to delivering cultural and systemic reform of the Home Office to ensure its policies are “rooted in humanity.” Cynics might note that Patel is the third successive Conservative home secretary to identify the need for comprehensive reform, and indeed that ministers have been making solemn pledges since Labour home secretary John Reid denounced his own department as “not fit for purpose” in 2006. At least for those going through our immigration system, the promised improvements have never materialised—as Yeo makes painfully clear.

But perhaps we should try to be more optimistic. For one thing, this time Williams has said she will be monitoring how much progress is made. Everyone involved in that exercise will need to read Yeo’s book, which delivers a powerful critique of the failings of the system and offers meticulously well-informed and realistic proposals for reform.

Yeo is the perfect guide for a tour of Britain’s broken immigration system. He is an immigration lawyer with years of experience helping individuals navigate the chaotic cruelty of the system. He is also an excellent and engaging writer (as readers of his Free Movement blog will know already), which is crucial when tackling a subject as complex and indigestible as immigration reform. He includes chilling accounts of lives ruined by Home Office policy.

[su_pullquote]“There is a horrific story of the detention and death of an elderly man with Alzheimer’s”[/su_pullquote]Immigration Enforcement staff worked with managers at the burger restaurant chain Byron to arrange a fake meeting for migrants they employed in central London. They told the staff different cover stories. “Some thought it was about a new recipe, while others were told it was about the dangers of medium and medium-rare cooking of burgers. In reality, the meeting was for the sole purpose of enabling immigration officers to detain, arrest and remove staff members without the proper paperwork.” Thirty-five people from Brazil, Nepal, Egypt and Albania were arrested, and sent to immigration detention centres. They were later removed from the country.

There is a horrific story of the detention and subsequent death in handcuffs of an elderly man with Alzheimer’s, who was unable to explain why he had breached immigration rules. There are accounts of an asylum claim dismissed by Home Office staff as a “pile of pants,” and of an under-qualified Home Office employee rejecting a claim because their confusion between guerrillas and gorillas led to the conclusion that the applicant was lying (“there are few recorded incidents of primates attacking humans”). Yeo’s transcripts from immigration interviews with asylum seekers (including questions to a refugee seeking asylum on grounds of sexuality like: “What is it about men’s backsides that attracts you?”) are revealing about the level of officially-sanctioned nastiness prevalent in the asylum system.

This is an extraordinary portrait of a system that matches incompetence with spite. Except, as Yeo points out, it isn’t really a system but a “cobbled-together conglomeration of incomprehensible and outdated laws, criteria that are set out in constantly shifting so-called ‘rules’ and apparently randomly privatised services delivered by the lowest bidder,” with rules evolving “chaotically in response to short-term political crises and economic pressures, with very little in the way of strategic planning.”

At times the book is unexpectedly funny. Yeo’s description of the alphabet soup of acronyms that he has to wade through during his daily work made me laugh, while also making me feel desperately sorry for him and the other immigration lawyers who must make sense of it all. To assess whether an applicant is eligible to remain in the UK, Yeo has to trawl through paragraphs E-LTRP1.2-1.12 and E-LTRP.2.1-2.2 in the immigration rule book annexes—“an interminable jumble of letters apparently generated by a toddler hitting a keyboard repeatedly and at random.” The rules are governed by Acts of Parliament from 1971, 1988, 1999, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2014 and 2016. The Immigration Act 2016 is 234 pages long, has nine parts, 96 different sections and 15 schedules. The Immigration Act 2014 is 137 pages long, has seven parts, 77 sections and nine schedules. Lawyers have to stay on top of it. Yeo quotes immigration judge Nicholas Easterman: “Immigration law is a total nightmare. I don’t suppose the judges know any more about it than the appellants who come before them.”

Yeo highlights the disconnection between the pride we take in ourselves as a tolerant and welcoming nation and the cruel ineptitude of our systems, contrasting the nation’s sentimental affection for the illegal immigrant Paddington Bear with the likely welcome he would receive if he had left Peru and stowed away now. Having committed the criminal offence of illegal entry, the bear would face up to six months in prison, Yeo notes. “Should he manage to avoid detection, he will be classed as an illegal entrant. That is where his problems really begin.” The hostile environment “is intended to make life in Great Britain intolerable for latter-day Paddingtons.” The image of Britain as a welcoming country with, as the Home Office press office likes endlessly to tell us, “a proud history of granting asylum to those who need our protection” is just a “comforting mirage.” Patel’s much-publicised appointment of a Clandestine Channel Threat Commander to counter migrants arriving in boats shows who we truly are.

Yeo’s piercing analysis of the hostile environment shows that it succeeds in doing little except alienating people who will eventually be allowed to remain in the UK in any case. “Having arrived full of hope, by then many are exhausted, alienated, disillusioned and often considerably poorer. Nevertheless, they are expected gratefully to integrate.” The policy is racist, he finds, causing “discrimination against citizens and settled migrants who are black and minority ethnic” because it forces untrained Home Office officials to make ill-informed judgments about who might or might not be an illegal immigrant.

The primary purpose of the hostile environment is to deter people from coming to the UK by making it as expensive, risky and inconvenient as possible; and for those who are here illegally, even just technically, to be forced to leave. The secondary purpose is to save money. Yeo can find no evidence that it has succeeded on either front. The policy looks increasingly like “a moral crusade to make life miserable for unauthorised migrants.” And it has been an abject study in failure: while “the financial costs of the red tape needed to set it up have been huge; there has been no discernible decrease in unlawful immigration.”

There is an urgent need for the hostile environment system to be reformed or abandoned before, as I explained in Prospect last year (“The Go Home Office,” November 2019), tens of thousands of EU citizens currently legally resident in the UK—and who, for whatever reason, have failed to do the paperwork to secure settled status during the transition period—suddenly find themselves similarly classified as illegal migrants. “Some will be elderly residents in care homes, some will be young children, others will not speak good English. Some may be afraid of applying and some will have believed the Leave campaign promise that their rights would be protected. Some will just be disorganised or unaware,” Yeo warns. “No matter their reasons, the effect of being exposed to the hostile environment will be the same. Their jobs will be lost, their bank accounts closed down, their tenancies terminated and access to the NHS and welfare benefits ended.”

Yeo has solutions as well as criticisms. Underlying his proposals is the eminently reasonable suggestion that migrants should be treated as citizens-in-waiting, rather than as undesirables we would like to see the back of. Given that there are between 600,000 and 1.2m unauthorised migrants in the UK, it is vital that there is a route to citizenship for them. “It is self-evidently undesirable that in the UK there should exist a large group of mainly black and ethnic minority non-citizens, who live and work in real communities but who can be easily exploited, with no access to proper healthcare, decent housing or the social safety net,” he writes. Sky-high immigration fees need to be reduced. A less punitive good character test should be introduced so that young people who have committed minor offences do not end up being barred from citizenship. He calls for a reduction in detention (over half of those in immigration centres are eventually released) and also the end to the principle of automatic deportation for many (which recently meant that twins born in London were told they faced deportation to two different countries they had never visited). The guiding principle should be that “migrants must be treated as humans.”

His conclusions chime with the Williams recommendations. Like Yeo, she concluded that the Home Office displayed “ignorance and institutional thoughtlessness” on the subject of race, found that the department was characterised by a “culture of disbelief and carelessness,” and displayed a “lack of empathy for individuals.” Like Yeo again, Williams argues that the Home Office “must change its culture” and calls on the government to introduce a new Home Office mission statement based on “fairness, humanity, openness, diversity and inclusion.”

Patel has committed herself to adopting this advice, in late July announcing that she had tasked officials “to undertake a full evaluation of the compliant environment policy and measures, individually and cumulatively.” Describing the Windrush scandal as “an ugly stain on the face of our country and on the Home Office,” she promised to review “every aspect of how the department operates, its leadership, the culture, policies and practices, and the way it views and treats all parts of the communities it serves. My ambition is for a fair, humane, compassionate and outward-looking Home Office.” Anyone with an interest in immigration—or for that matter human decency—should pay close attention to see that she honours that commitment.

Welcome to Britain: Fixing Our Broken Immigration System

by Colin Yeo (Biteback, £20)