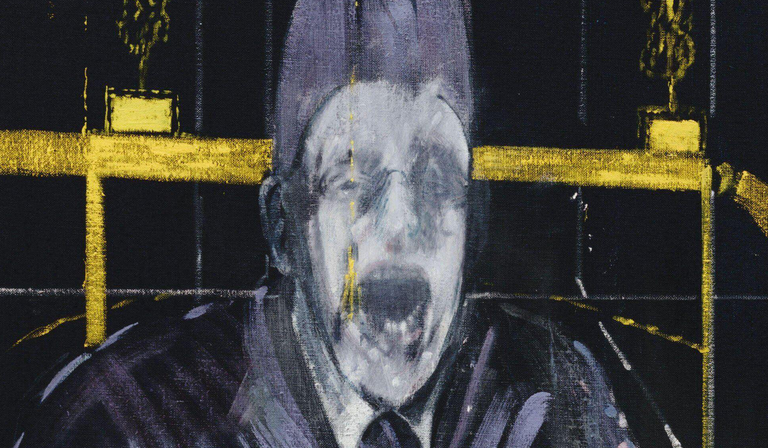

It is recognised by many, from journalists to philosophers, politicians to psychotherapists, that we are living in an age of anger. Some date it back to 2016, when Donald Trump became president for the first time after a campaign in which he said he would “gladly accept the mantle of anger”, and when the UK voted to leave the European Union in a decision fuelled at least in part by xenophobic rage. Some trace it a little further back, towards the turn of the century, when all the things we had worried about during the age of anxiety—automation, disconnection, isolation—actually started to happen, and there was nothing for it but to rail against them. Some simply attribute it to social media. Certainly, in 2025, it’s easy to find evidence of—and rationale for—our widespread collective anger, from cataclysmic political and religious divides to the petty, childish ire we feel at a machine informing us that there’s an unexpected item in the bagging area.

All that may be true, but the British journalist Sam Parker nevertheless thinks anger gets a bad rap. His new book, Good Anger, is not the first recent publication on the topic—Pankaj Mishra’s 2017 Age of Anger charted the rise of extremist and reactionary politics in the late 2010s; in 2018, the writer and activist Soraya Chemaly published Rage Becomes Her, a book about women’s anger; last year the psychoanalyst Josh Cohen published All the Rage, about how anger became a defining feature of society and politics—but it is unique in its documentation of his own personal experiences with anger: how he transformed from someone who “didn’t really get angry” to someone who is able to acknowledge anger for what it is and channel it in a healthy way. Inspired by his learnings from therapy and a eureka moment with a punchbag in the gym, Parker investigates the physical, psychological and historical meanings of anger—“the black sheep of the emotional family”—with the help of friends and experts.

Good Anger is not about the stimuli that have plunged us into this particular age of anger. Rather, it floats the idea that if we were all better able to accept our anger as a natural part of being human, we might find that other problems, such as anxiety and depression, are lessened. Parker is clear that anger does not have to equal aggression: the bullying, explosive or domineering behaviour that perpetuates its bad reputation. But the fact that “we use a word for a healthy emotion interchangeably with one describing attacking and hostile behaviour” has a damaging effect: “We tend to avoid talking about it altogether until it has boiled over.” Counterintuitively, we may even find that by giving anger its due, we can become less aggressive, have more constructive conversations and generally feel a lot better.

Parker is clear that anger does not have to equal aggression

Some of these ideas are derived from Freud, who was the first to theorise not only that “unexpressed emotions never die”, but that depression was “anger turned inwards”—suicide being the most violent act possible, committed against oneself. But beyond psychological concepts such as trauma, repression and transference, which Parker talks about largely in relation to workplace anger, it is the fear and avoidance of anger at a societal level that is most intriguing. The idea that you might be transferring repressed rage at your mother onto your boss may prove useful if you would like to behave less like a three-year-old in the office—but the same psychotherapeutic principles apply to all emotions. The difference with anger is that many of us walk around pretending it doesn’t exist, only to find ourselves suddenly seeing red. The most fundamental question is why it became taboo and now bubbles up collectively, particularly online, in great, society-wide actings-out.

Parker traces the demonisation of anger to the ascetic monk Evagrius Ponticus, whose categorisation of eight evil thoughts in 375 AD would eventually become the seven deadly sins, where anger found itself nestled somewhere between lust, greed and sloth (three other concepts, incidentally, that can be easily transmuted into contemporary cultural phenomena, such that they become porn, consumerism and what TikTok lovingly refers to as “rotting”). The message became embedded: if you are angry, you are not a good person. Yet what also lingered was the idea that some people are allowed to be angrier than others. The anti-anger rule didn’t apply to God, whose anger “existed on a separate plane”, writes Parker. “This justification for violence would prove crucial to how Christianity extended its reach around the world in the form of Holy Wars, crusades and the persecution of heretics.”

On both societal and individual levels, powerlessness is the cause and effect of such avoidance. God is the only one allowed to be angry; he is also all-powerful, and his anger makes that power more immediate and terrifying to those who are not afforded the same privileges (the same basic principle could be applied to problematic individual relationships, parental, romantic or professional). Parker’s quest to reconcile himself with his anger, and to encourage others to do the same, is in no small part about not being a doormat—and setting what are now often referred to as “boundaries”. Anger, he writes, is “a firm but loving voice telling us to stand up and fight on our own behalf”. Thomas Aquinas, heavily influenced by Aristotle, wrote that “those who are not angry at the things they should be angry at are thought to be fools … for such a man … is thought to be unlikely to defend himself”.

But as much as anger breeds power, it is also the case that power sometimes breeds anger. After all, if you feel you are entitled to something, you are more likely to be angry if you don’t get it—whether this derives from a sense of omnipotence that needs to be dismantled (from a toddler in the mirror phase to a misogynist demanding sex) or simply a quiet confidence that you deserve better. When Parker interviews the journalist Helen Lewis, she points out that “sometimes the higher your position in society, the easier it is to be angry because the more you’re used to people caring when you’re angry”. You need a certain amount of power to be angry in the first place.

This seems crucial to understanding why the internet is such an angry place. Social media has transformed culture not just because of the frequency and pace at which it enables us to communicate, but also because of the way in which it ostensibly leavens everyone’s status. We are inhabiting the same spaces, using the same functions and subject to the same rules, as world leaders and A-listers. Our posts pop up on the same screens. Our words are written in the same font. What this means is a fundamental change in power dynamics, including the power we perceive ourselves to have—and therefore how much anger we feel willing and able to express.

Today, people can hide behind avatars and not face consequences for their anger

The anonymity of the online world also changes the texture of anger. It means people can hide behind an avatar and not face consequences. Even partial anonymity online, where we might display our real picture but not our real name, results in us being associated with broad-brush identity markers (from nationalities to star signs), which can in turn make us feel safe. As Parker writes, it’s more acceptable to express anger on behalf of a group than as an individual, particularly if you’re from a marginalised community: “Black people can be angry in pursuit of equality; a black person expressing anger on their own behalf is out of control or a threat.”

Social media is not an example of the “good anger” that Parker wants us all to tap into. He draws on the work of the psychologist Carol Tavris and psychotherapist Aaron Balick, both of whom touch on the idea that, to be productive, anger needs to be received in the right way and reach a resolution. Getting angry online is the equivalent of the “rage room” that Parker tests out in the book with mixed results: paying to smash plates brings a certain degree of catharsis, but you’re no closer to the conclusion that your anger was willing you towards.

Yet, despite Parker’s assertion that social media is “a room of people ostensibly shouting at each other, but really playing out psychodramas from their own past and present”, there is more to online rage than psychological resolution. Anger goes viral because we are bored—and we are bored because we are nihilistic, because we have lost faith in causes and politics, because provoking an extreme physiological response is the only way to make us care. We are terrified of stopping because we are terrified of more boredom. And what is boredom if not a kind of powerlessness, when we are unable to harness the world for our own entertainment or purpose?

Parker’s message is clear. Let anger be. Channel it. Don’t let it bottle up. Everyone—no matter their age, background, gender or race—should have equal anger opportunities. Because anger left to fester has profound psychological, physical and societal impacts. But if there’s one other conclusion to be drawn from Good Anger, it’s perhaps that our age isn’t uniquely angry—we just don’t know how to let it out.