Should we be making opt-out schemes for housing deposits? Workplace pension reforms are a triumph of the Coalition Government. Heavily influenced by the work of this year’s winner of the Nobel Prize for Economics, Professor Richard Thaler, they have transformed pensions saving.

Since the scheme was introduced in 2012, over 6.7 million people have been automatically enrolled. The government expects that, once fully-rolled out by 2020, 10 million workers will either be newly saving or saving more in a workplace pension scheme.

Thaler was right: public behaviour can be nudged in a positive direction. The scheme has been a success. Such a success, in fact, that it should now be reformed to address another of the country’s ills.

In the past few decades levels of home-ownership have plummeted. Yet it has taken two fingers from the under-50 electorate for the political class to clock a trend which is reshaping people’s lives and which all evidence suggests will continue to.

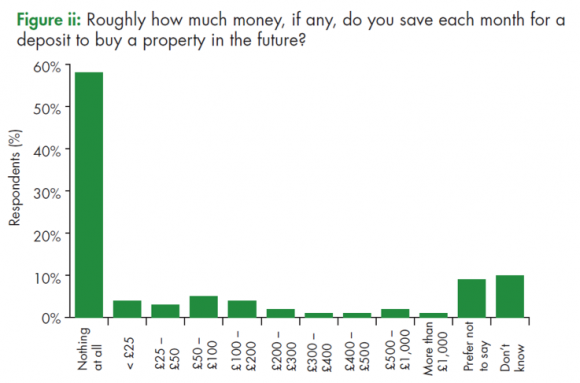

Research from Localis finds that fifty-eight percent of people who do not already own their home outright or with a mortgage are saving nothing at all each month for a deposit to buy a home in the future. Just twenty-three percent are saving anything towards a deposit (the remainder didn’t know, or declined to answer).

These figures should frighten any government. For one whose votes tend to come from homeowners and the mortgaged, they should terrify. The foundations of the home-owning democracy are weakening year-on-year. And yet government’s response has been tepid at best.

If government makes the choice that the home-owning democracy is something worth preserving—as it has and should—then it has to take a more muscular interest in deposit saving. Its laissez-faire approach is failing.

This is where Thaler’s work, and the successes of the workplace pension scheme, can be latched onto and reforms made. Government should introduce auto-enrolment for deposit saving. Instead of, or alongside, a pension, workers should be given the choice to contribute towards a mortgage deposit (via a Lifetime ISA).

Like with the current scheme, employers would make contributions equal to three percent of the employee’s qualifying salary (paying no more or less than before) and, as with the Lifetime ISA, government would continue to match twenty-five percent of employee contributions.

Extending the auto-enrolment scheme to mortgage deposits in this way would go some way to improving savings coverage. It would also accelerate the rate at which someone can save. You would save. Your employer would save. And government would help too. This is something that, despite how they are often portrayed, the young overwhelmingly want: the most recent English Housing Survey finds 80 percent of 16-24 year olds who privately rent expect to own their home in the future.

The table below shows what a person on a number of salary levels could expect to accrue. A mortgage would be in reach much more quickly for all.

| Salary | Total savings after 1 year | Total savings after 5 years | Total savings after 10 years | Total savings after 15 years |

| £20,000 | £1,271 | £6,356 | £12,712 | £19,067 |

| £25,000 | £1,721 | £8,606 | £17,212 | £25,817 |

| £30,000 | £2,171 | £10,856 | £21,712 | £32,567 |

| £35,000 | £2,621 | £13,106 | £26,212 | £39,317 |

| £40,000 | £3,071 | £15,356 | £30,712 | £46,067 |

| £45,000 | £3,521 | £17,606 | £35,212 | £52,817 |

Some will not agree with the diverting of savings away from pensions to mortgage deposits. Yet without reform, home-ownership becomes a preserve of (very) high-earners and those with access to parental wealth.

I do not believe this is the kind of country the government aspires to. Banks and building societies have already established Lifetime ISA products, making the scheme transition simpler than starting from scratch, while the financial benefits and security of owning your own home will for many people be greater and more immediate than upon receiving a pension at pension age. Indeed to a large extent a house is a pensionable asset already.

It is often said the housing crisis is one of supply. And they are right: not enough homes are built, or already built, where people want to live. Yet this should not preclude government focus and funding from supporting younger generations onto the housing ladder. From the landed gentry to Thatcher’s boom in home-ownership, the housing market has always reflected the lines along which wealth has been divided across British society. Unless government takes a firmer stance on deposit saving, the great intergenerational divide of our time will become entrenched: where only the very old and very rich can afford to be very wealthy.

Read more about Localis' work on reforming the housing market.