The beatification of Harold Wilson, especially in the Labour Party, is a wonder to behold. Tories always had a grudging admiration for the master tactician who won four of the five elections in the turbulent decade between 1964 and 1974. But his name was mud among Bennites and Blairites alike in the years from his resignation in 1976 until the end of the Blair era. To the Labour left, he sold out; to the right, he didn’t sell out—or “modernise”—enough. His previous biographers were ambivalent at best. His tawdry resignation honours list—wealthy tycoon James Goldsmith et al—cast a long shadow.

Now it is all change. This proudly revisionist and unstintingly admiring biography is by MP Nick Thomas-Symonds, who sits at the heart of Keir Starmer’s frontbench. It is warmly endorsed by the Labour leader himself, who names Wilson as his model predecessor. The book is deeply researched and an excellent read; its stated mission is to “make the case for Wilson as one of the 20th century’s great politicians.” Its subtitle “The Winner” is applied to far more than general elections. With considerable skill, “he led his party and the country through acute economic difficulty and profound social change,” writes Thomas-Symonds. “With a brilliant mind, sure-footed political moves and an instinctive feel for public opinion, Wilson was a survivor who emerged from crises to defeat political opponents time and time again.”

This is probably too revisionist. Wilson failed to resolve arguably the biggest single challenge of his era: endemic conflict between trade unions and the state. The failure of Barbara Castle’s 1969 “In Place of Strife” white paper, which called for ballots and “cooling off periods” before strikes, meant the middle ground was lost, and ultimately led to Margaret Thatcher’s neoliberal train. His resignation in 1976 was the action of a leader drained of energy and purpose, who had promised so much more a decade earlier when he famously lauded the “white heat of the technological revolution.”

But time changes perspectives. The rehabilitation of Wilson is in large part a bitter commentary on the signal failures of the last two decades. With his European referendum, seen as deeply shifty at the time, Wilson kept Britain in the EU by a popular majority of two to one in 1975—a veritable miracle compared to Cameron’s 2016 Brexit referendum and abject defeat by Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson. Roy Jenkins and Labour’s other pro-Europeans were infuriated that he played both sides—but it was the result that mattered most. At the end of Jenkins’s life he saw it that way, too, and wrote a warm appreciation of Wilson.

Still, in my view the 1975 referendum was Wilson’s major error—not because of its result but because of its precedent. Until then, there had never been a national referendum in Britain and there were powerful political and constitutional arguments against the innovation. The rest is history.

During the 2003 Iraq War, a stark contrast was drawn between Wilson’s skill in keeping British troops out of Vietnam and Tony Blair joining the Americans. Wilson’s policy was taken for granted at the time, but the pressure on him to fall in behind Lyndon Johnson was as great as anything Blair experienced from George W Bush. At the time the Labour left was infuriated by Wilson’s failure to condemn Vietnam, but again it was the result that mattered most: there were no British body bags. This was the first stage in Wilson’s rehabilitation, on the left especially. Thomas-Symonds makes the Vietnam/Iraq parallel explicitly and is notably cool in his references to Blair.

Even on the trade unions, the complete breakdown in relations with the state (and the major strikes that followed) happened under Macmillan, Heath and Callaghan—before, in between and after Wilson’s two governments. There wasn’t a major strike under Wilson. It is implausible that the guileful Wilson would have been as inept as Callaghan in setting the pay ceilings that led to the Winter of Discontent between 1978 and 1979—or ducked calling an election, for which Labour was well placed, in autumn 1978.

If Wilson didn’t solve the “union problem,” he managed it better than any other prime minister of his period. In his “social contract” with the Trades Union Congress and the major unions, he created a middle way between legal regulation and voluntarism, which just about worked until the late 1970s. To blame him for Thatcher misses out the three crucial years between him leaving Downing Street and her entering it. If, as he said, “a week is a long time in politics,” the Winter of Discontent was a political eternity.

Then there are the great liberal reforms—the end of capital punishment, allowing no-fault divorce, the first race relations legislation and the decriminalisation of homosexuality and abortion. Jenkins was the prime mover as home secretary, but Wilson gave him free rein. In addition, the reforms were mostly done by backbench legislation, which didn’t involve the whips or collective Cabinet responsibility. Mindful of his heavily Catholic constituency near Liverpool and the working-class Labour vote, Wilson did not participate in any of the 50 votes on abortion and homosexuality during the passage of the legislation through the Commons. This was quite a feat of commission and omission. Thomas-Symonds says he was personally a “social conservative,” but still his governments heralded radical social change.

Wilson also had a sharp eye for the political danger of unrestricted immigration. At the time his curbs on Commonwealth immigration were controversial on the left. But here again, acting as he did in 1968, he probably stemmed a full-scale revolt led by Enoch Powell and his supporters. It is notable that there were almost as many people leaving the country as arriving between 1968 and the expansion of the EU in 2004.

Further feathers in the Wilson cap are the expansion of social housing and higher education. The 1960s and 1970s saw the creation of much of the nation’s council housing—imperfect, but so much better than the slums they replaced. Wilson personally pioneered the Open University, which transformed higher education opportunities for primary school teachers and many other professions. A swathe of new universities and polytechnics were built on his watch, accelerating the march towards today’s mass higher education system.

A meritocrat and egalitarian with no social pretensions, Wilson expanded the welfare state and personified the political triumph of the grammar schools over the private schools—albeit only temporarily, partly because under him Tony Crosland pioneered the abolition of the grammars. It was not inevitable that Heath, Major and Thatcher, all grammar school educated, would be succeeded by Etonians. Tellingly, Starmer is one of the last of the state grammar school boys from Surrey.

Wilson was an electoral machine, true, but he was so much more. And had he not been so much more, he could never have been such an electoral force. This obvious point will influence the next generation of Blair studies, too—another “winner” who was so much more.

Four themes stand out from this biography. The first is Wilson’s sheer professionalism. Top of his year in PPE and then an Oxford don, wartime civil servant and assistant to Beveridge, MP and minister at 29, Cabinet minister—president of the Board of Trade—at 31: there had been nothing like it since Gladstone a century before. The contrast with today’s Tory and Labour leaderships could not be starker.

Wilson was as much “liberal” as “labour.” At Oxford he started off as a Liberal, and was thereafter pragmatic about the means to achieve progressive ends. He was never wedded to wholesale nationalisation and sought to extend it in only a handful of sectors. But by deft political footwork—theme two—he made himself the leader of the Labour left after Aneurin Bevan, while never getting too close to him personally. He resigned alongside Bevan from Attlee’s government over NHS charges in 1951, but didn’t object as Bevan did to higher defence spending per se. His tortuous formulation was that it was “a rearmament programme which I do not believe to be physically practicable with the raw materials available to us.” Three years later he re-joined Attlee’s frontbench.

Thomas-Symonds applies more widely the analogy of the Scilly Isles, Harold and Mary Wilson’s remote holiday spot off the Cornish coast, where Mary wrote poetry and Harold played golf. It was classic Wilson “to be part of something yet apart at the same time,” as the Scilly Isles are to the UK. “Wilson could travel overseas for his holidays yet remain in the UK.”

Wilson was an electoral machine, but he was so much more. And had he not been so much more, he could never have been such an electoral force

Or rather, in England. For the third theme of this biography is Wilson’s pan-English quality. He was a professional Yorkshireman, a professional Londoner, a professional Scilly Islander—and appeared like a reassuringly professional bank manager, with his pipe, raincoat and three-piece suits. Wherever Middle England was in the 1960s, there was Harold Wilson, together with the Beatles, Coronation Street and Bobby Moore’s winning World Cup team.

It is a striking fact that Labour has only ever won general elections outright with English leaders representing English constituencies. Attlee, Blair and Wilson all, at their peak, won majorities over the Tories from England in England. They were never alien forces, or capable of being portrayed as such, in the nation which makes up 85 per cent of the UK.

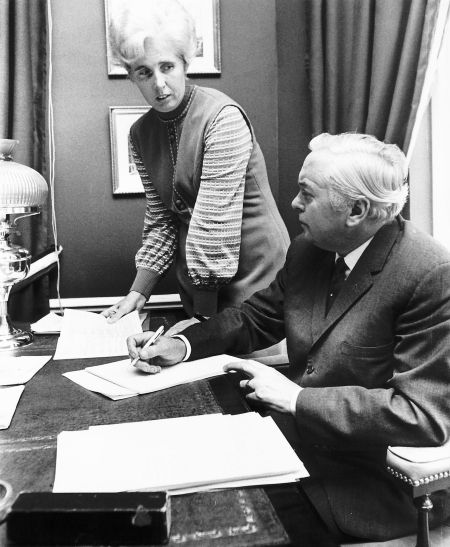

Thomas-Symonds suggests that Wilson’s greatest quality was his “adaptability.” Interestingly, he attributes much of this quality to the influence of his “right-hand woman,” his long-term aide Marcia Williams. A career Labour Party operative, “she was the one who could read his speeches and advise on how the Labour movement would receive them.” They never had an affair, but “she was the one who was always there, at his side, both as a political support in the loneliness of leadership and also someone who could provide him with emotional support and affirmation.” Elements of this closeness existed in Wilson’s relationship with the Queen too, as portrayed deftly in The Crown—another act of rehabilitation.

One of the most intriguing suggestions in the book is that Williams “was closer to the centre of power in 10 Downing Street” than any woman until Margaret Thatcher. Ambivalent as ever, maybe that was one of the ways that Wilson blazed a trail for the next generation.