Sometime in the spring of 2013, a taxi driver picked up Xi Jinping in central Beijing. At the time, Xi was settling into his job as head of the Communist Party of China and would soon be appointed president. Later, the driver, who had bragged about his famous fare on the internet, responded to sceptics who claimed it was a case of mistaken identity by saying that he knew precisely what Xi looked like. He produced some calligraphy his passenger had given him. They had discussed the environment, the driver went on, and the problem of balancing economic growth with high GDP.

Many continued to dispute the story. It seemed unlikely that a man in command of the world’s second largest economy and second highest military spending after the US, the leader of 1.3bn people, might be allowed by his security detail to wander the streets of the capital alone. Usually, it was hard for even top-level colleagues to get close to him. A photograph taken a couple of years later shows Xi getting into a car after an inspection tour with an army of minders forming a human wall around him. And yet China’s official news agency, Xinhua, confirmed the taxi driver’s story—before hastily removing it a few hours later. Censors eradicated other memory traces left behind in Chinese cyberspace.

To this day, no one knows if Xi was indeed the man the taxi picked up. But a few months later Xi undertook a similar journey, queuing at a small eatery for steamed buns and soup. There he sat, placidly eating his food with a presumably well-trained audience of fellow humble eaters around him. The difference between this and the taxi journey was the huge scrum of minders and media that had come along to record Xi’s performance as a man of the people.

Xi should be an easy person to categorise. Unlike his predecessor, Hu Jintao, for whom the term “a man of no qualities” was an almost perfect description, Xi’s biography is relatively well known—and for good reason. He rose not from obscurity, but as the son of a high-level leader from the Mao era. Xi Zhongxun, his father, was a soldier in the wars before the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949. Despite his son’s populist airs today, Zhongxun was part of the new elite. After the Communists were victorious he became a vice premier, before in 1962 being put under house arrest for alleged political disloyalty—a story to which we will return.

Whether or not his background has made Xi a hardcore conservative Maoist, or something more complex, there are two things we can definitely say about him. The first is that on issues such as combatting climate change, dealing with pandemics and trying to cure the world’s economic ills, international leaders have no choice but to reach some kind of agreement with him and the country he leads. And secondly, underestimating him has proved—and will continue to prove—extremely perilous. While it clearly irks leaders in democracies, the brute fact is that Xi is a formidable operator. And while Vladimir Putin may be the figure who most triggers western fears, it is Xi who casts the greatest shadow. He is leading his country to the final chapter of the “End of History” while delivering an unexpected punchline—a communist, one-party state ending up as the world’s most successful capitalist economy.

Xi was born in 1953, the third of four children by his father Zhongxun’s second wife. Until the age of nine, he enjoyed the life of the new Red elite. At that time, China was experiencing relative stability and optimism after the calamities of war and revolution in the first half of the century. But when Zhongxun was accused of promoting a work of fiction seen as critical of Mao, he was detained by the authorities. For much of the next 16 years he was absent, in prison or under house arrest.

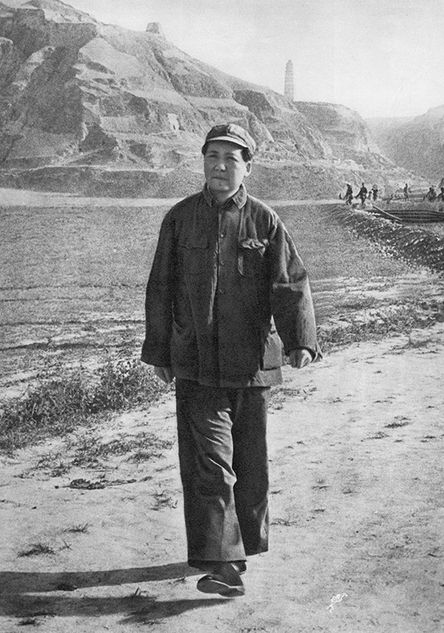

His absence made the family rely heavily on Xi’s mother, Qi Xin—still alive, aged 95. It also produced a sense of insecurity that typified a generation of Chinese people coming of age as the Cultural Revolution loomed. From 1966, interfactional battles among the elite downwards almost led to a civil war. By 1969, Xi, now a 16-year-old student unable to attend shuttered schools and burdened with a “bad class” label because of his father’s actions, was shipped off to a rural area. In hindsight, the choice to send him to Yan’an—a central area of China that had served as the main base for the communists during the Sino-Japanese War—was lucky for him. That Xi spent almost seven of his most formative years here is used today to show off his impeccable political credentials. Like Mao, he is seen as a peasant emperor, combining the country and city life of China in his own life story.

Testimony from other young people sent to Yan’an at the same time shows that rural life was far from easy. Farmers were often hostile to the callow city youths imposed on them. The food and living environment were harsh. One of the main complaints was the constant mosquitoes at night. However, contemporary narratives claim that during his time there Xi showed his authentic links to the countryside. He also proved his devotion to the party, trying to join nine times before finally overcoming his bad family background and succeeding. His time in Yan’an also gifted him his first political role: he became party boss of a village in 1974.

The end of the Maoist period saw Xi back in Beijing, now able to re-enter education after universities re-opened as the Cultural Revolution wound down. After studying chemical engineering at the elite Tsinghua University, he worked in the late 1970s as the assistant to Geng Biao, a leading military leader. Now his father had been rehabilitated, and Xi rejoined the elite that had been so downtrodden in the previous decade and a half. He briefly married the daughter of an ambassador, though his decision to stay at home when her father was posted to the UK led to the end of the relationship. His second marriage a few years later was to one of the country’s most famous singers, Peng Liyuan; they have one daughter.

Xi is now branded a Maoist because of his autocratic, nationalist style of politics, and the propaganda and worship accorded him. On the 120th anniversary of Mao’s birth in 2013, Xi dutifully visited a seminar where he made suitably respectful comments. While he might have borrowed some of Mao’s political tricks, what Xi privately thinks about the “Great Helmsman” is another matter. Mao was the leader responsible for his father’s long incarceration but, in the end, Xi and those of his generation are survivors of the chaos created by Mao; he may feel more gratitude than resentment. Xi has the zealotry of a convert. He is a born-again Chinese communist, whose rebirth after what looked like certain family and personal annihilation has fated him, he believes, to be where he is today.

Those who knew Xi as a local official in the 1980s and 1990s were struck by this confidence and sense of destiny. Planning and ambition mark his subsequent career. Deciding to leave the military in 1982, Xi moved into civilian administration where political power was on offer. He worked first at a village area in Hebei province near Beijing; then, around 1985, he was sent to Fujian. This huge, dynamic coastal province facing Taiwan underwent rapid economic growth in the 16 years he worked there. Investment flooded into the cities, factories and infrastructure. Special economic zones were created in places like the city of Xiamen where Xi was mayor. After the party’s shock at the 1989 uprising, the government recommitted to economic development. Party leader Deng Xiaoping had made this crystal clear when he went on his famous final tour to the southern part of the country in 1992. “There was,” he said, looking over Shenzhen, the city that had almost risen from scratch as the late 1970s reforms started, “only the road to reform or the road to perdition.” Fujian was at the vanguard of this reform.

That commitment to material improvements in people’s lives and pumping up GDP growth may have prevented perdition, but it created plenty of other challenges. It damaged the environment and sent inequality through the roof. It also threw up political threats. For the party itself, the greatest of these was the massive rise in corruption. Through the boom years, from the 1990s up to 2010, China’s economy quadrupled in size. Entry to the World Trade Organisation in 2001 helped turbo-charge growth, creating a decade-long boom that prevailed as the rest of the world underwent something close to an economic cardiac arrest during 2008. In the period one writer labelled “the fat years,” double-digit growth was the norm. Party officials on their modest salaries, with their puritanical communist creed, found themselves in a sea of excess. Living in China and travelling around at this time was like witnessing a carnival. The landscape physically transformed, with one-storey traditional houses in hutongs replaced by gleaming skyscrapers in a matter of weeks. Motorways were constructed to criss-cross the country. In Xi’s Fujian, one fixer, businessman Lai Changxing, had most of the local administrators in his pocket through payoffs, collusion and blackmail, spiriting away billions of dollars in a smuggling scam.

The corruption ended when central investigators descended in the late 1990s. Dozens of officials were taken in. Lai himself fled to Canada, before being returned over a decade later. Xi was one of the few who were untouched. Perhaps that was something to do with a belief he expressed in Fujian and also in his next posting as the party head of Zhejiang province near Shanghai, a position he held from 2002 to 2007. Speaking to Xinhua news journalists in the mid-1990s, he said one “could not be an official and do business.” There needed to be boundaries between the two worlds. And yet, it was precisely for the opportunity to do big business that many wanted to become cadres in the first place. For delivering this pure but unpopular message, and because of his own elitist background, by 1997 Xi was still deeply out of favour with others in the leadership and failed to get elected by his peers onto the Communist Party central committee. No one then would have looked at him and thought that in a decade’s time he would be a contender for the top job.

Xi’s belief in politicians staying out of business has been consistent. In the writings he issued online while in Zhejiang—he was one of the earliest communist leaders in China to see the power of the internet—by far the most frequent topic was the need for the party to regulate its affairs and for party officials to be clean. “Party bosses are too keen to be good mates with everyone,” he complained at one point. He argued they had failed to be truthful to their ideology. They were busy looking after their own personal networks, not the wider society around them. They were slothful, complacent, and all too often on the take. This lacerating language came close to the tone the newly-appointed Pope Francis used with his fellow priests. Xi, the born-again communist, certainly sounds like a man in the possession of a creed he feels others are not living up to. For him, the party is like a religious community, with the chosen making their way to an earthly paradise they risk jeopardising through larceny, laziness and lack of political grip. What is most important is fidelity to the party, its message and its historic mission.

For a leader like Xi, while it is economically useful for China to pose as a capitalist country, that is only a means to the more important end of becoming a powerful communist nation. We can say little about what Xi might believe in detail about Marxist ideology. But it is in no doubt that he believes sinified Marxism has, since 1949, given the country unity, focus and the tools to become what it is today. The past is not a foreign country for Xi and his generation but an ever-present influence. It is a harrowing story of exploitation and victimisation by the Japanese, British and others and, from 1911 to 1949, almost complete implosion. Xi and his party see economic success, guided by their shared and hard-won creed of socialism with Chinese characteristics, as a far surer guarantor of national greatness and strength than nuclear weapons or any other military tool. The belief that Chinese communism delivers national success is Xi’s core conviction—one that has become more entrenched as his time in power has continued. Maybe this is why in 2007, despite a field of other well-qualified contenders, he emerged finally as the chosen replacement for the incumbent Hu. In one-party systems, a peaceful transfer of power between generations of leaders is never easy. The Soviet Union’s record of purges and machinations after Stalin and then Khrushchev had proved this. The Chinese record has been little better. But despite the high stakes and his relative lack of previous experience, what is striking about Xi’s elevation in 2012 was how relatively seamless it was.

For sure, Bo Xilai was one of Xi’s elite competitors until he was implicated in a murder case (Bo’s wife was convicted of killing a British businessman). That dramatic story drew a lot of attention in 2012. So too did rumours of unrest and even attempts at a military coup by figures loyal to Bo. Xi himself briefly went invisible in September of that year, stirring up yet more excited speculation, mostly because it meant visiting US secretary of state Hilary Clinton was not able to hold talks with him. A few weeks later in mid-November Xi emerged, as had been expected, as the newly enthroned party boss. Since then, it has been Xi all the way.

“Through absolute control of any viable space for organised social or political opposition, Xi’s party dominates”

On the day of his appointment, Xi delivered a short manifesto from the main stage of the Great Hall of the People. His message was clear. The Communist Party could not rule anyone if it could not run its own affairs. The distance between leaders and the people had increased, Xi said. Within months, his formidable colleague Wang Qishan began an onslaught on official misbehaviour that, unlike anti-graft clampdowns in the past, reached deep into the party infrastructure: former top leaders were targeted—the tigers, not just the flies, to use party language. Concerted efforts were made to instil uniform and correct ideology into the rank and file. Right down to basic levels of government, cadres who had violated their promise to “serve the people” were taken in, serving as a sobering example to those who had been spared. Xi, like Odysseus finally meeting Penelope, returned to find the Communist Party maltreated and demeaned—and wreaked vengeance on all those who had taken part in this mass violation.

Xi’s confidence and sense of destiny came to the fore. He insisted that the years of China being humble, low profile and silent during the Hu era were over. With a true propagandist’s instincts, Xi focused on the critical importance of having a positive story both for Chinese people and the wider world about the country’s renaissance. The party’s chief ideologue, Wang Huning, termed this story the China Dream. Wang in fact had served as the main thinker for Jiang Zemin in the 1990s, and then Hu in the 2000s, and his work is inscribed across the party edifice—giving the lie to the idea that Xi offered a radical ideological break from his predecessors. The difference is one of intensity. Wang has finally worked with a leader, Xi, who absolutely subscribes to the notion that party culture is key—the need to have a belief system that people actually acted on, informed by not just Marxism-Leninism but traditional Chinese thinking. From 2013, therefore, its leaders made stronger appeals to the idea of the Communist Party being not just the custodian of China’s future and present, but the great defender of its past. This resurgence of cultural confidence has happened precisely as the west has been going through a long-term decline in self-esteem. These two processes have resulted in our current tense geopolitics.

The New Cultural Revolution under Xi has achieved its goal of creating an iron-like sense of discipline in the party. Through fear as much as conviction, officials in Xi’s China are obedient and, on the surface, loyal and well behaved. The party’s absolute political centrality has been restored. Through the commanding role of state enterprises, through absolute control of the military and reducing any viable space for organised social or political opposition, the party dominates. Xi gives the vast capacity of the state a human face—though just how much he is directing this is hard to state.

Even more remarkable has been the party’s use of technology. Face recognition, artificial intelligence, extensive data analysis and constant monitoring of online forums to keep an eye on the public mood has given the state capacity as never before to penetrate the lives of its citizens. Once, even in the Mao era, the inner worlds of Chinese people were largely a mystery. Even when officials demanded sincerity and obedience, it was hard for them to work out if what they got was simply playacting. But “Deep China” (as this place is called by sociologists) is now present and analysable via the online activities of a billion-plus netizens. Xi’s image has managed to enter into that intimate space, through the intense efforts made to build a leadership personality cult with emotional nationalism at its heart.

This is helped by the fact that the Xi-era clampdown on corruption and disciplining of the Communist Party has proven popular for the changing demographics of the country—the service sector-working, urban-living, high-consuming middle class. With 60 per cent of the population now living in built-up areas, many of them middle-income, Xi’s China is not the overwhelmingly rural China of Mao. Xi might admire Mao, but he cannot simply duplicate his style of rule. They governed different places. For example, the party proudly announced in early 2021 that absolute poverty had been eradicated. For a country whose average life expectancy was 31 years for men in 1949, this is a remarkable achievement. And yet, Xi seems to have ambitions that lie beyond this.

“Xi’s mission, the reason he has been given the kinds of powers he has, is to make one-party rule sustainable”

As well as making his middle-class supporters wealthier than they ever have been, Xi wants to ensure they are citizens of a powerful country, one that has had its status restored as sitting at the centre of the world. Just as with all other post-1949 leaders in China, nationalism is the great fuel that fires the Xi project, and the heart of the message that keeps him alongside the new Chinese bourgeoisie. There at least he is aligned with Mao, another fervent Chinese nationalist. In particular, the dream of reuniting with Taiwan looms over Xi. Were he to offer a solution, his position in history would be assured. But as of 2022, that seems as elusive as ever. Today the people of Taiwan, a quarter of a century after introducing democracy and alienated by the crackdown in Hong Kong, are more willing than ever to describe themselves as Taiwanese rather than Chinese.

Despite the vast powers imputed to him abroad, this core task of keeping his emerging middle class happy is not an easy one. As the pandemic struck, fears of an economic implosion caused the government once more to pump out promises. Around February and March 2020, Xi looked like he was in trouble. The Wall Street Journal carried the provocative headline “China, the Sick Man of Asia” and had its journalists booted out of the country. Donald Trump’s administration had become aggressive to the point of obsession against Beijing. Once more, for around 10 days, Xi disappeared.

Once more, however, his fortunes took an unexpected turn. The western countries that had been berating China and declaring that the Covid-19 pandemic was the People’s Republic’s “Chernobyl Moment” started to be struck by high infection rates themselves. Suddenly, democracies too were being exposed, their administrative limitations made clear, their political leadership often appearing rancorous and inept. All the anger and blame levelled at China by the outside world for its management of the virus, with claims of cover-ups and worse, seem to have only bolstered Xi’s position domestically. It is unlikely the average Chinese person cares much for Xi Jinping Thought, enshrined in the constitution in 2017, and advertised as a body of ideas that answers all of the country’s current challenges. But they do respond to Xi-style nationalism. That Xi clearly troubles the outside world is no bad thing for them. Having a feared leader, and one who has the US on the back foot, is largely a big plus for the modern Chinese middle class.

For all the pious declarations by outsiders saying they wish to save the Chinese people from the tyranny of their own leaders, it is more likely, as Xi moves towards almost inevitable re-appointment for another five-year term at the Party Congress later in 2022, that his mandate is stronger now than it was a couple of years ago. This is despite Covid-19’s immense domestic disruption and costs. Chinese people look at democratic politics with a far more nuanced, less naive view these days. They see noisy, harmful divisions in the US, and remember their own history of catastrophic civil wars.

One cannot ignore the dark side of Xi politics in all of this. The extensive abuse of human rights in Xinjiang, where documents, satellite imagery and other powerful testimony have shown a million or more people largely of Uighur ethnicity placed in detention to be “retrained” has been toxic for China’s international brand. For dissidents and social activists, things have never been quite as bad as they are today. Technology has been the great enabler for the Xi party state, used with no moral scruples. Hong Kong’s limited autonomy has vanished to the point almost of non-existence. A Chinese leader like Xi with his constant stress on the “bigger picture” would, if ever quizzed about these issues, no doubt simply reply that for the vast majority of Chinese people their country is getting better. And as this is almost a fifth of humanity, that is good news for everyone else.

Whether Xi’s style of party leadership, his diplomacy and politics really will keep that key group—the Chinese middle class—fully onside in the decade ahead is another matter. Xi’s mission, the reason he has been given the kinds of powers he has, is to make one-party rule sustainable. The Soviet Union failed in this. No other major country has achieved it. If he succeeds, it will have implications not just for his own country, but for the rest of the world. He will prove one of the core tenets of modernisation theory—that only democracy can get you a developed, wealthy society—is untrue. This will be not just a geopolitical upending, therefore, but an intellectual and ideological one, the impact of which will sweep across the planet. As of 2022, it is hard to look at all that has happened in the last decade, and not feel he has a fighting chance.