We do love a good equation, don’t we? It might be culturally acceptable, even fashionable, as Prospect has recently pointed out, to say that we are utterly dunder-headed at maths, but seemingly that does nothing to undermine our delight in a good equation. By good, I mean an equation that tells us something useful about our lives: how to make the perfect cup of tea, when is the most depressing day of the year, what makes the perfect airplane flight, or how England’s football team can improve its chances of winning the World Cup. (That last one was surely right, because Stephen Hawking came up with it.)

Some scientists can be very sniffy about this kind of thing, saying that these equations for the perfect doughnut/date/beach read are meaningless PR stunts that have zero science content. (With Stephen Hawking? Surely not!) Others will argue that they’re just a bit of fun, a way to get science on the news agenda and perhaps to encourage the public to see how a scientist breaks a problem down into cause and effect factors, and turns it into something quantifiable. That is presumably the thinking behind the latest “perfect equation”, offered by the Director of Engineering and Education at the Royal Academy of Engineering, which tells us how to select the Perfect Poohstick.

I can’t help wondering if this is a double bluff. Might the RAE perhaps be more interested in discovering whether the public and the media know what an equation actually is? If so, they might not be too surprised to find that knowledge lacking at the Daily Mail, though it is rather more alarming to see that neither the BBC nor the Guardian newsdesk has the faintest idea either. (I exclude those organs’ exemplary science writers, who will be pulling their hair out.)

You see, the Perfect Poohsticks equation doesn’t actually mean anything. I don’t mean that it doesn’t work (though I’m coming to that). I mean that it is not an equation. It’s just a collection of sciency-looking symbols.

Do I have to explain Poohsticks? Can there be anyone out of nappies who hasn’t seen that timeless illustration from AA Milne’s The House at Pooh Corner in which Christopher Robin stands on the rail of a bridge, a branch poised in his hand ready to drop into the stream of the Hundred Acre Wood, while Pooh and Piglet peep over the edge at their own sticks? The idea is simply to see whose stick emerges first on the downstream side of the bridge. So embedded in British culture is this simple game that today DCMS even tweeted some instructions on how to play the game safely, before strangely deleting the tweet and then issuing an apology. There is as yet no perfect formula for removing all traces of unwanted tweets from the internet.

Now let’s take a look at the Poohsticks formula:

PP = A × I × Cd

A perfectly good equation, yes? I mean, algebraic symbols either side of an equals sign—what more do you want?

If this isn’t sciency enough for you, the RAE has mustered some wonderfully precise numbers about public attitudes to Poohsticks. Apparently, 57 per cent of Britons think that the game is pure luck; 41 per cent of players “take the time to personalize their sticks”; 30 per cent just grab the nearest long, thin stick; and only 11 per cent pick the right kind of stick. Bloody amateurs.

Here’s the thing about equations: the symbols represent some property that can take different values. And we’re told that they do so here: A is the cross-sectional area of the stick, I is the stick’s density, Cd is an impressive-sounding quantity called the drag coefficient. And PP? PP is “the Perfect Poohstick”.

Wait, give me that again. PP is the Perfect Poohstick? But that’s not a quantity. That’s a thing—a stick thing. Well alright, perhaps I’m being pedantic. Perhaps we should simply be calling PP the Perfect Poohstick Index or something, and the idea is that the bigger PP is, the better the stick. So then I need to maximize PP, as an engineer would say.

That’s simple. I look for the biggest tree I can find, chop it down, and chuck it in. That, after all, gives me a large value of A, the cross-sectional area. Perhaps I can just grab a log off a nearby timber pile.

Hmm, that didn’t work very well. Let’s try something else. How about if I maximize the quantity I, the density? Look, if I rip this steel bar from the railing, that will do the job—it’s a whole lot denser than wood.

Oh. No luck there either. I must be missing something.

Alright then, we’d better take a look at this drag coefficient thing. But then it all gets horribly complicated, because the drag coefficient—the amount of drag experienced by an object as it moves in water—depends on so many things, such as its shape, its orientation in the flow, its surface texture, the speed at which it moves… What this means is that a given stick doesn’t have a given drag coefficient; this depends on the specifics of the situation. But look, here’s the point the equation is trying to make: if the stick is rough, with bits of protruding bark to catch the flow, it will be borne along more easily, with the protrusions acting like paddles. I’m a bit troubled by this, though. How do you then compare different sticks and figure which is best for a given stream flow speed? Does the length matter? Side branches? And what’s this Dr Morgan is saying about “a certain roughness can make the stick ‘apparently’ smoother, similar to the effect created by dimples in golf balls”? Oh, and fluid mechanics tells me that the drag coefficient for a cylinder is inversely proportional to the cross-sectional area, so won’t any benefit I get from making A bigger be cancelled out by a larger A making Cd proportionately smaller?

Oh, I know, I know—I’m taking this all too seriously. Poohsticks is meant to be fun. It’s just that the Poohsticks equation isn’t helping me to enjoy it, because it doesn’t seem to help, and in fact seems to imply nonsensical things.

That’s because it really does. Even if you take the trouble to turn it into a real equation, it is transparently wrong. It doesn’t show how to think about the problem scientifically, but just makes it look superficially sciency.

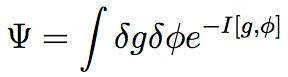

The real reason this depresses me—apart, that is, from the acceptance in the media of a scientific gloss that is so uncritical, one has to conclude they could be sold absolutely anything if it has algebra in it—is that it gives a false idea of what science is and how it works. Any problem, it implies, can be reduced to a fancy-looking equation, and then all you need to do is plug numbers into it. If you believe Stephen Hawking, you can even do this for the whole universe. Hell, why don’t I give it to you:

In which case, it’s hardly surprising that it’s so easy to pull the wool over people’s eyes with Poohsticks.

One commenter on the Guardian report expressed disappointment that a story about finding the Perfect Poohstick was not all about how to find the ideal implement for clearing up dog shit. I think I could do with that right now.