Rearranging the deck chairs in public service management structures is almost always a pointless and expensive displacement activity. It is the last refuge of governments wanting to divert attention from their own failings or—worse—a ploy to distract from problems caused by underfunding, by declaring war on “the system.”

Matt Hancock’s touted reorganisation of the NHS, less than a decade after his Tory predecessor Andrew Lansley last reorganised it from top to bottom at huge cost and controversy, doesn’t even have a rationale which makes sense.

His claim that reorganisation is needed to increase ministerial control and foster collaboration between NHS organisations is a comical non-sequitur. You don’t need a new command-and-control system to empower front line collaboration: just do it.

Prospect’s analysis of what’s going on contains the highly revelatory line from the leaked White Paper on what is to replace the status quo: “ADD DETAIL LATER.” As the “off-with-their-heads” Queen of Hearts put it long ago in Alice in Wonderland: “sentence first, verdict afterwards.”

Ministers already have massive formal and informal power over the service, although Simon Stevens, the NHS chief executive, strikes pretty much everyone as more competent and focused than his ministerial masters. He is also vastly experienced, having spent his whole career in health policy and management in the UK and US since starting out as an NHS management trainee after a misspent—but politically educational—youth on the same Oxford Union executive as Boris Johnson.

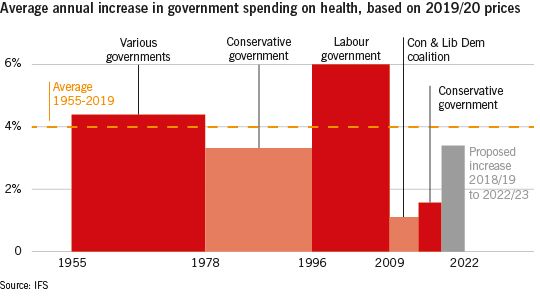

Crucially, ministers alone control the funding lever, which is the elephant sitting on all the deck chairs. The NHS’s biggest problem (see graphs) is money, not structure. Faced with burgeoning patient demand, its rate of funding increase in the last decade has been lower than at any time since the NHS was created 70 years ago. For much of the austerity decade, spending has grown at less than half the historic average of 4 per cent a year. Even with recent improvements, resources are only growing at roughly the rate of the Thatcher/Major years and barely half that under New Labour. Instead of growing as a share of the economy, as was the established trend in our aging society, since 2010 King’s Fund figures show the health service has been shrinking.

Anyway, what non-financial failure is this reorganisation intended to address? Covid-19 has shown the NHS to be well worth its reputation as, to quote Nigel Lawson’s rueful expression, “the closest thing the English have to a religion.”

The best part of the UK’s response to Covid-19 by far is the rollout of vaccines, a triumph for the NHS with its highly collaborative GPs and existing leadership. “Beware ministers seeking to assert control over the NHS,” warns Lord Adebowale, chair of the NHS Confederation. “The NHS is already one of the most centralised health systems in the world.

As a public service moderniser masterminding Tony Blair’s quest for “education, education, education,” my greatest successes came from surgical interventions with special funding, particularly the “London Challenge” to transform the capital’s comprehensive schools, new academies to replace the worst failing secondary schools nationwide, and a massive expansion of teacher recruitment including Teach First to attract a new generation of the brightest and best graduates into state school teaching. There was no system-wide structural upheaval, just system-wise investment and expectations of rising standards.

Universities were transformed for the better by equally surgical funding injections, sustained increases in research investment, incentives to recruit more overseas students, and a student fee system with income-tested repayments which is, in effect, a graduate tax—all accomplished without any wider structural reorganisation. A wholesale overhaul would have been a massive distraction, perhaps dooming the reforms which really made a difference. Tellingly, the one education sector constantly rewired by the Blair/Brown government was further education, to no good effect.

So my strong advice: remember that NHS stands for National Health Service—not New Health Structures.