By the government’s own admission, the housing market is broken. It isn’t building enough homes—and those that are being built are often unaffordable and poor quality.

New research from Shelter shows that eight out of ten working families who are renting privately cannot afford a newly built home in their area, even with Help to Buy.

Not only are these homes out of reach of normal families; further Shelter research conducted with YouGov showed that half of new home owners have experienced major problems with their properties; including with construction, unfinished fittings and faults with the utilities. The ongoing Bovis Homes scandal bears out these findings.

But these problems can all be tackled—if a sensible, civic-minded solution is pursued.

Britain’s housing crisis is systemic: our main way of building homes has evolved over time to benefit landowners and speculative developers, whilst families and communities pay the price. There are no moustache twirling villains here (generally speaking), just some serious winners and serious losers from a completely clapped out system of housebuilding.

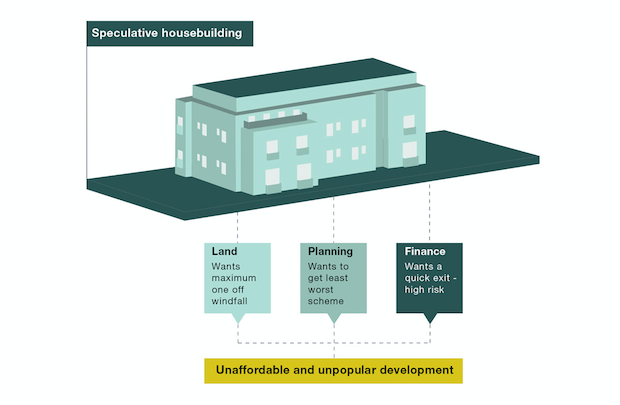

This reliance on a “speculative” model of housebuilding is particularly concerning. This means developers compete against each other to offer the highest price for land, which inevitably drives up the price of the homes they build.

The upshot of this speculative frenzy over land is that developers have to cut corners, ensuring they cover their costs and make good returns. This often results in unaffordable, low quality homes that don’t meet the needs of local people.

And to be clear—it’s not just people trying to find a new home who lose out, it’s existing homeowners and communities too.

Our planning system asks developers to contribute towards local roads, schools and general infrastructure when they build new homes in an area, in order to help sustain it. But once they’ve paid an astronomical amount for the land, these facilities can be argued to be “unviable,” so are dropped from the plans and the local authority has next to no real power to enforce them.

In short, it means the deal which gets struck works out for the developer, works out big time for the landowner, but fails the local community.

This also creates the ideal environment for NIMBYism—and who can blame this group when the homes are this poor? Our recent research also showed that 83 per cent of NIMBYs who have actively opposed housebuilding would happily have more homes in their area, if they were more affordable or generally better designed.

It really does not have to be like this. This speculative system is just one way of building homes—and it’s the wrong way. So let’s turn the page and try something new: here’s where Shelter’s New Civic Housebuilding comes in.

This model of building homes works by giving local authorities more control over land in their area. This in turn allows them to lower the cost of land, and ensure it is used to build the homes that local people actually need.

For this to work, landowners would have to accept a lower, fairer sum up front for their land. They could also invest their land for the long-term, meaning that they take their return over time, while actively helping to create a far better place for their community.

This would help redress the balance in the land market. As it stands, once agricultural land is granted planning permission for housebuilding, its value soars by 328 per cent. The landowner then receives an enormous windfall profit at the stroke of a pen, having contributed nothing to warrant it.

More of the land value generated by planning and new development needs to be shared with the local community. That means affordable homes for local people to live in and the services and infrastructure needed to help those communities thrive.

This approach has serious weight behind it—not least because it already has a proven track record. From the beautiful New Town in Edinburgh to the great Georgian strands of Bath, the Peabody estates to the New Towns: they were all built using the same underlying civic-minded principles.

The idea has some fairly well-established backers, too. Joseph Chamberlain understood the importance of the value of land, as did Winston Churchill and even King James II, who, when speaking about the building of the Edinburgh New Town, said that landowners should be “obliged to part with the [land] on reasonable terms” and to use it “in favour of the citizens.”

So not only is the problem clear, the solution is too. All that remains is that essential yet mercurial final ingredient: political will. We need to revive the successful Civic Housebuilding of the past in order to consign our housing crisis to the history books.