Between 1919 and 1939 four million new homes were built in England; a million by local authorities and three million by the private sector. These were the legacy of David Lloyd George’s “Homes for Heroes” vision to give a better life to returning servicemen after the Great War.

In the 1930s over 300,000 homes a year were built—many of them in the huge “metroland” London suburbs like Harrow, Brent and Barnet. These homes were mostly built by thousands of small and medium-sized housebuilding companies, local to their area, building some homes for the council, and some for private buyers.

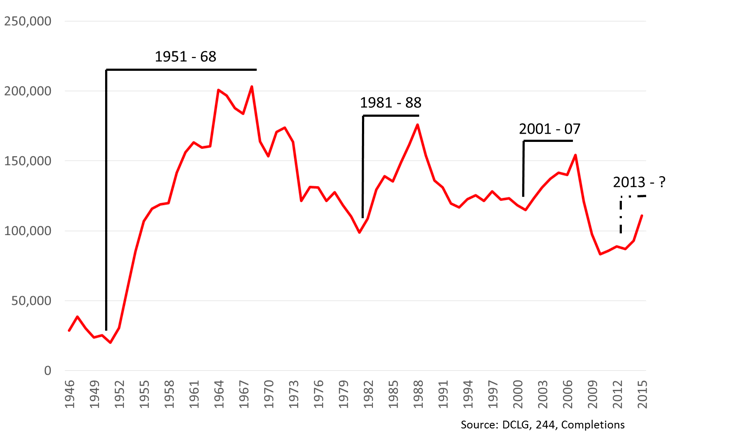

The story is, to put it mildly, quite different today. The most recent housebuilding “peak” of 2006/07 gave the UK just under 220,000 new homes, and was followed by an almighty crash in construction in the aftermath of the banking crisis. Since then, we’ve been trying to make up lost ground—but with under 140,000 houses built over the last year in England we still haven’t gotten close to the pre-recession level, let alone the 250,000 minimum per year that we need.

Homes now are predominantly built by large firms operating on a speculative development model. They buy land years before they build expecting to sell to a mix of subsidised first-time buyers and buy-to-let investors.

This model isn’t delivering at the scale we need. Our latest projections from Capital Economics suggest that housebuilding will decline by almost 8 per cent over the next year in the wake of the EU referendum and the surrounding uncertainty. If this happens, it would follow the postwar trend of market housebuilding ratcheting down after each economic shock—never recovering back to its previous peak before the next downturn (see graph).

Private Market Housebuilding, England (1945 – 2015)

It’s worth going over the history, not just to restate the failures of modern housebuilding policy, but also to show more positively that things can change. We have built enough homes before and we can do so again. While the situation may be bad, it is eminently fixable.

First we must come to terms with the fact that the current model of housebuilding just isn’t working. It is not the fault of one government, one prime minister, or one part of the private sector, but an accumulation of policies which have come to skew the housing market in favour of speculators and away from the consumer.

In theory, high demand for homes should mean developers build more and sell at a competitive price. But with housing, the land market acts as a crucial preliminary link in the building chain, which front-loads the system with higher costs and stymies the competitive pressure which should balance supply and demand.

And land, of course, isn’t unlimited. Developers compete for the best sites in the right places—normally in or around cities and near transport links. The lack of sites leads to hugely competitive bidding by developers, which in turn triggers a race to the bottom in the quality, size and affordability of the homes that can be built. Spending less on affordable housing, or housing quality, means a higher price can be offered to the landowner. What’s more, once the land is bought, homes mustn’t be built too quickly. Too many homes built at once would mean that sales prices were undercut.

There’s no point lambasting large developers and land owners for doing this because it all makes business sense. But it does mean we are left with a dysfunctional market where the developer who offers the worst deal for the consumer wins the site, and where smaller firms simply cannot compete.

Clearly then, there is a strong case for reform.

The most important change that must happen is for housebuilders to be able to get their hands on land at a steady price, which lets them compete on quality and price for the consumer. This isn’t a utopian fantasy—it’s how house building works in many other countries. In the land-restricted Netherlands, for example, local development plans are backed by strong local powers to buy land at a reasonable price. In Germany, the local authority can freeze land values through the planning process and then provide sites at a reasonable price for the country’s huge self-build sector.

We could incorporate these principles into our planning system in England. There should be much stronger powers of intervention for communities to get the sorts of development they want in their area: high quality, affordable, with the right infrastructure. For example, where landowners or developers refuse to comply with Local and Neighbourhood Plans there should be an option to buy the land off them at a reasonable price which makes development viable.

This new approach should include public sector landowners too. With just 8 per cent of the government’s target for public land release for homes met as of July this year, this is clearly an area on which the government can improve. Public land should be scrutinised for opportunities and small sites made available to SME builders on long-term models to share the development profit.

Let’s remember, this is not simply a numbers game—the stakes are very high. For many people the aspiration of owning a home is looking increasingly like a distant fantasy.

The societal costs are huge as generations put their lives on hold; for example, some people are delaying starting a family because they’re renting in shared accommodation. And at the sharp end we are looking at the prospect of rising homelessness, increasing levels of poverty and a further growth in inequality. Insecurity abounds and ambition is being stifled for whole generations.

Beyond the economics, a decision from the government to properly reform and rebalance the land market and get Britain’s smaller firms building again would be enormously symbolic. If done right, this could be a bold claim for the middle ground, sweeping up many young and disillusioned voters by providing homes and well-paid jobs. It would show a clear investment in solving long term problems, not tinkering around the edges. It would show a government which is willing to get to the roots of a problem and solve it for the benefit of people today and generations to come.