Britain’s two-party system is in intensive care; can it be revived? Before exploring the possibilities for the future, let’s examine the clues provided by recent history and the operation of the first-past-the-post voting system.

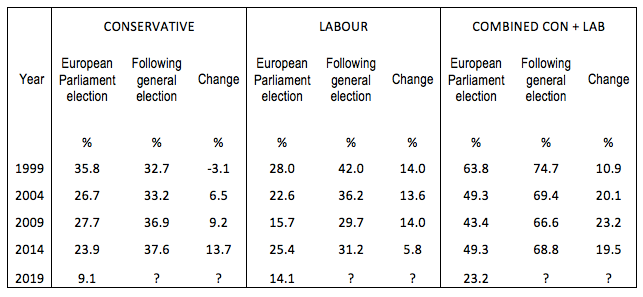

Last week saw the fifth elections to the European Parliament fought in Britain under the (roughly) proportional d’Hondt voting system. The following table shows how Labour and the Conservatives fared in each election, compared with their support in the following general election.

Those figures tell us two big things. The first is that there is little relationship between European election performance and support at the subsequent general election. Second, after each of the last three European Parliament elections, the combined support of the two parties climbed around 20 points at the following general election, from 43-49 per cent to 66-69 per cent.

Last week, of course, the combined vote of the two parties crashed to just 23 per cent. If the pattern of the past 15 years is repeated, their combined share would rise to no more than 43-46 per cent. The two-party system would be in deep, possibly terminal, trouble.

Is that likely? If we have an autumn election, with Brexit not sorted, then plainly the Brexit Party could capture millions of traditional Tory votes. As in 2015, when Ukip won four million votes but only one seat, Nigel Farage’s party may have few, if any, MPs in the new parliament; but it may win enough votes in Tory-Labour marginals to cost the Conservatives victory.

However, it will be not only the Tories whose future would be at risk in an autumn election. Last week’s election showed Labour suffering at the hands of the Liberal Democrats and Greens. Had Jeremy Corbyn campaigned strongly for a People’s Vote, Labour would have done far better. Hence the signs since the election that Corbyn may now back a fresh referendum, shorn of the qualifications that have muddied the picture until now.

Would this do the trick? Probably; but it would need Corbyn to campaign for a referendum with enthusiasm. His half-hearted contribution to the Remain cause in 2016 arguably contributed to the cause’s defeat. If he advocates a People’s Vote with the enthusiasm of a hostage forced to read out statement that his captors have written for him, it will do the party little good.

All this makes the outcome of an early election impossible to predict with any accuracy. The contest, manifestos and campaigns will matter. So will the performance of the minority parties. The Liberal Democrats seem to have recovered much of the ground they lost after joining the coalition in 2010. After nine years, the party’s strongly anti-Brexit cause has finally trumped memories of the tuition fees fiasco. There is a reasonable chance that the Lib Dems would end up with at least 20 MPs—possibly 30 or more if enough ex-Labour converts stay with the Lib Dems.

In Scotland, the SNP seems to have arrested its decline. My guess—it would have 30-40 MPs in the new parliament (roughly the same as today). Add in one, and possibly a second, Green MP (the second in Bristol), four Plaid Cymru and—this can be no more than wild speculation—3-5 of the 11 Change UK MPs keeping their seats, and we could have something like 60-80 third-force MPs from the British mainland. On top of that will be 18 MPs from Northern Ireland, although these currently include seven Sinn Fein MPs who don’t take up their seats in Westminster.

Bottom line: there is a real prospect, perhaps a likelihood, that we shall have another hung parliament; and if either Labour or the Conservatives do end up with an overall majority, it is likely to be a small one, as in 2015. The numbers are unlikely to be there for sorting out Brexit easily (if the Tories win) or implementing a left-wing manifesto (if Corbyn becomes prime minister).

Combine all these factors, and it is likely that the next parliament, whenever the next election is held, will be a mainly two-party parliament, but not as overwhelmingly as during the first 40 years after the second world war, and probably not producing the kind of majority that a prime minister would need if s/he is to secure parliamentary support for radical decisions.

That, though, will not be the end of the story. First-past-the-post elections make it perfectly possible to weaken our two-party duopoly, but hard to destroy it. Yet, ten years from now, I doubt whether British politics will look the same. Two fundamental developments—one building up over 50 years, the other more recent—look certain to come to a head. The first is that far fewer people identify with either Labour or the Conservatives than half a century ago. Indeed, this is one reason why the combined support of Labour and the Conservatives last week was only 23 per cent. Voters have increasingly deserted the two main parties in second-order elections (for local councils, the European Parliament and in by-elections); and, with the exception on the 2017 contest, to some extent at general elections. The long-term secular trend towards smaller parties is likely to resume.

Whether this trend will lead to a breakthrough at a future general election will depend on the second, more recent, development: the fact that political opinions are now driven far more by values in general, and Europe in particular, than by economics and social class. Our two-party system will survive in the long term only if Labour and the Conservatives adjust to this reality. This will require tough choices by both parties. The Tories must choose between outward-looking social and economic liberalism on the one hand, and a more nationalist, more interventionist strategy on the other. Labour must choose between the liberal values of highly educated metropolitan voters on the one hand, and the more conservative values of its traditional working-class supporters on the other. For both parties, the recent national arguments about immigration and Europe have both symbolised and intensified these choices.

My tentative conclusion: 20 years from now, if we still have first-past-the-post elections to the House of Commons, we shall still have a two-party system of some sort; but the names and character of the two parties are far from certain. As in the aftermath of the First World War, when the Liberals gradually gave way to the Labour Party as Britain’s dominant anti-Conservative force, there may be years of turbulence before we reach that destination