Read former cabinet minister David Willetts on what the Coalition got wrong on welfare

There is an economic case for welfare reform. The government shells out more than £200bn a year on pensions, child support, unemployment benefits and help for low-paid, sick and disabled people. If it could make real inroads into that budget, it could reduce the deficit faster, cut taxes, spend more on schools, hospitals and new homes—or some combination of all three.

There is also a moral case for welfare reform. If too much goes to people who don’t deserve their benefits, or don’t really need them, this offends our sense of fairness, provokes resentment among taxpayers and, many of us fear, creates a dependency culture.

In the weeks ahead, we can expect all the parties to make both arguments as they set out their policies for reforming our benefits system. The trouble is, the public debate is based on fundamental misconceptions among voters which few politicians are prepared to dispel. The misconception is that the same policies will tackle both the moral and economic problems. They won’t, for the simple reason that the two problems are completely different; but none of the main parties seem willing to say so. With welfare, as with many other election controversies, most politicians prefer to pander to voters’ fears rather than confront them.

The public misconceptions are clear from YouGov’s latest survey for Prospect. Most voters vastly overstate the amount that is spent on benefits for the unemployed, the level of fraud, the degree of “welfare tourism” by immigrants and the proportion of people who lose their jobs and go on to claim jobseeker’s allowance for more than a year.

According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, crunching data from the Office for National Statistics, Britain’s total welfare bill in 2013/14 was £205bn. This is almost a third of all government spending, and as much as it raises from income tax and corporation tax combined. By far the biggest component is state pensions. Together with pension credit, the total comes to £90bn. Benefits for families with children (mainly child benefit and child tax credit) total £37bn a year. Almost as much, £36bn, goes to sick and disabled people. A further £34bn helps people on low incomes; two-thirds of that takes the form of housing benefit.

By far the smallest category comprises benefits for unemployed men and women: just £4.5bn at the latest count, or a mere 2 per cent of all welfare spending—a far cry from the 34 per cent believed by the average voter.

As for fraud, if the average in our poll, 22 per cent, were correct, then more than £40bn would be received each year by people fiddling the system. The Department of Work and Pensions’ latest estimate is that £3.4bn is wrongly paid—but that most of this is due to “official error.” Only £1.2bn is the result of fraud. That is still £1.2bn too much. It’s a tidy sum that could be spent on other things. But it’s nowhere near the public’s estimate.

Likewise with “welfare tourism.” There is no official figure for the amount of jobseeker’s allowance, housing benefit, child benefit and child tax credits that are currently being claimed by people who have come to Britain in the past 10 years. But the total cost of all these benefits is £76bn, or 37 per cent of the total. Recent immigrants comprise no more than 5 per cent of the population; academic studies indicate that they are less likely than British-born people to receive welfare benefits. This implies a total “welfare tourism” bill of 2 per cent of the £205bn total—possibly less, and certainly no more than 3 per cent. That compares with the public perception, which averages a whopping 23 per cent. Once again, this is not to justify the present state of affairs, just to put it into context.

Nor can these figures be explained simply by the way most people misjudge the relative expenditure on pensions and other welfare benefits. Last autumn, YouGov asked how many of the two million or so immigrants from the rest of the European Union were claiming jobseeker’s allowance. The true figure is around 60,000. The median answer in our survey was 300,000—rising to half a million among UK Independence Party voters.

This is one of the issues at the heart of the Conservatives’ plans to renegotiate Britain’s relationship with the 27 other countries in the EU. Should we have the right to tell people thinking of coming here that they won’t be able to go on the dole, at least for some time? The moral case can certainly be argued. Perhaps people should not be able to claim money from the government unless or until they have paid something in first. But if anyone expects such a measure to make a noticeable difference to Britain’s welfare bill or the number of people settling in Britain, they will be gravely disappointed.

When it comes to long-term unemployment, ministers deplore the “lifestyle choice” of people who manage to continue claiming unemployment benefits for the long-term when they could have a job. Around 100,000 people a month lose their jobs. We asked respondents to estimate the percentage of new claimants who go on to receive jobseeker’s allowance for more than a year. The public’s average estimate is 38 per cent; the actual figure is 10 per cent.

That 10 per cent then needs to be divided into those who genuinely can’t get a job and those who could if they tried, but manage to fool local benefits officials into believing otherwise. By definition, no such figure exists. But as unemployment benefits in total comprise just 2 per cent of all welfare spending, only a fraction of 1 per cent can be attributed to long-term, “lifestyle choice” scroungers.

Explore the data:

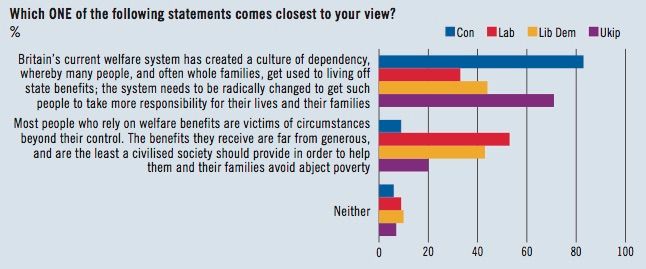

The public’s misconceptions about welfare colour their views of the overall impact of the system. Fully 57 per cent believe that it “has created a culture of dependency.” This is closely linked to the views about specific measures. The more people exaggerate the degree of fraud or long-term unemployment, the more likely they are to blame a culture of dependency, and the more they blame the system as a whole for being too generous. Of those who endorse the “dependency culture” thesis, fully 66 per cent say that our benefits system is too generous. Among the 30 per cent who believe that “most people who rely on welfare benefits are victims of circumstances beyond their control,” only 5 per cent say the system is too generous.

As might be expected, people who blame the “culture of dependency” are more likely than the rest of the public to overstate the amount of money going to fraudsters, immigrants and the jobless. However, the difference is not huge: even people who embrace the “circumstance” view of welfare also tend to overstate the money spent in these politically sensitive areas. It looks as if the devotion of the media to stories of welfare “abuse,” and of politicians to promising to address such abuses, has shaped the perceptions of the vast majority of voters—even those who are on the side of claimants or are, indeed, recipients of welfare benefits themselves—not least the biggest group of beneficiaries: the elderly. Among the small minority who broadly understand how our welfare spending is shared out, few think the system is too generous or generates a culture of dependency.

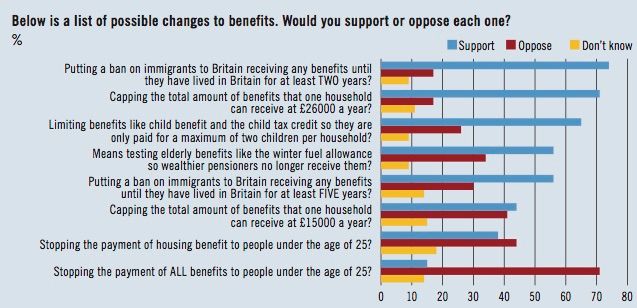

I doubt if any minister would admit to welcoming, far less encouraging, the public misconceptions that we have uncovered. However, they have benefited from it. There is strong public support for a number of the measures they have advanced since 2010, such as capping the total amount of benefits that any one household can receive at £26,000 a year, and banning immigrants from receiving benefits until they have lived here for at least two years. The only measures that have been floated that do not meet public approval are curbing the access of young adults to benefits. Just 15 per cent would scrap all benefits to the under 25s, while a higher number, though still a minority, 38 per cent, would force them to live with their parents (or someone else willing to give them free accommodation).

As for means-testing older people so that well-off pensioners stop receiving winter fuel allowance and other universal benefits, the public divides 56-34 per cent in favour; but the over-60s are rather less enthusiastic. Ed Miliband supports a curb on winter fuel payments for richer pensioners, but it’s a moot point whether this will do Labour much good. This is because the people who would feel most strongly are precisely those who would lose out, who happen to be the people who are most determined to vote. And it would save only £200m at most, or 0.1 per cent of the total welfare bill. The larger truth is that none of the “popular” welfare reform measures would make much of a dent in the £205bn welfare bill. However strong the moral case for them, they would have little impact on the nation’s finances. In the long run, by far the biggest savings are likely to come from raising the age at which workers qualify for a state pension.

Explore the data:

The current plans are to raise the age to 66 in 2020, and to 67 by 2028. My guess is that the process will have to be accelerated. I would advise anyone under 40 to plan to work until they are at least 70 before expecting a state pension—and, if they enjoy above-average incomes, to assume that they will receive little from the government, for the means-testing of state pensions must be one of the options that a future government will almost certainly have to consider.

There is a more radical alternative: change the savings-and-pensions system completely so that people have more choice over, and take more responsibility for, the way they save for their retirement—subject to a statutory minimum. This could reduce the welfare bill to taxpayers significantly, albeit at the cost of requiring workers to save more of their salary.

But however you carve it up, the interaction of rising life expectancy (hooray) with our frighteningly expensive national welfare bill (oh dear) means that for big savings we need to look to the elderly, not scroungers, fraudsters or immigrants. And this means politicians taking on a growing, high-turnout and popular section of the electorate, and to stop pretending that going after the easy and unpopular targets will make much of a difference.

I would go further, for the public’s views about welfare reflect a wider mismatch between belief and reality. Surveys find consistently that people think things are worse than they are. Two of the great social advances of the past 10 or 20 years have been the marked reduction in crime and the sharp fall in the number of teenage pregnancies. Yet when people are asked about these things, most say they are bad and getting worse.

Likewise with living standards. We believe that they are no better than a generation ago when in fact we are, on average, more than 50 per cent better off. Today’s Britain has many problems but compared with, say, the 1980s, we are richer (especially pensioners), live longer, make fewer unwanted babies, endure fewer muggings and burglaries, smoke less, have access to far more and cheaper information and entertainment, are better educated, celebrate a far wider variety of cultures and lifestyles, breathe less polluted air, enjoy cleaner beaches and suffer less infant mortality and child poverty. Yet when Ukip comes along and demands a return to the Britain of yesteryear, many of us say “yes please.”

Even more alarmingly, we think our children will not be as prosperous as us when they reach our age. This goes beyond the perfectly reasonable view that we are struggling to recover from recession. When we ask people specifically to look beyond the next few years and consider the long-term future, they remain pessimistic.

Unless the world is afflicted by something terrible to do with war, terrorism or sudden climate change, such pessimism is surely unwarranted. Over the long term, growth is a result of human ingenuity, technical advances and more-or-less open markets. These things are unlikely to disappear, even if we have to put up with greedy banks, dishonest business leaders, unjustified monopolies and incompetent politicians.

Maybe we must simply live with this pervasive bias towards gloom. The trouble is, it distorts our politics. In this spring’s election campaign, politicians from all the main parties (Ukip is not alone in this) will offer solutions to problems of the public’s imagination, rather than confront misconceptions and offer voters an alternative narrative about the state of Britain today.

How refreshing it would be for at least one party to say that most things are actually getting better, and that we should fret less about “welfare tourists” who are rare, claimant fraudsters who don’t cost us much, crime which is falling and pensioners who have never had it so good. Instead we should devote our energies to tackling the real problems we face, such as too few affordable homes and proper apprenticeships, and too many privately-educated white men in top jobs. (Yes, I know every party says it wants to put these things right—but they give them a lower priority than policies designed to stroke the electorate’s prejudices.)

Welfare reform sits squarely on this fault-line between myth and reality. It sets every major party a stern test: to state honestly that the things most people want will save little money—and that to save big bucks we need a radical rethink of the benefits going to pensioners today and in the future. On their current performance it is a test of both political morality and national economics that every major party will duck.

Explore the data:

There is an economic case for welfare reform. The government shells out more than £200bn a year on pensions, child support, unemployment benefits and help for low-paid, sick and disabled people. If it could make real inroads into that budget, it could reduce the deficit faster, cut taxes, spend more on schools, hospitals and new homes—or some combination of all three.

There is also a moral case for welfare reform. If too much goes to people who don’t deserve their benefits, or don’t really need them, this offends our sense of fairness, provokes resentment among taxpayers and, many of us fear, creates a dependency culture.

In the weeks ahead, we can expect all the parties to make both arguments as they set out their policies for reforming our benefits system. The trouble is, the public debate is based on fundamental misconceptions among voters which few politicians are prepared to dispel. The misconception is that the same policies will tackle both the moral and economic problems. They won’t, for the simple reason that the two problems are completely different; but none of the main parties seem willing to say so. With welfare, as with many other election controversies, most politicians prefer to pander to voters’ fears rather than confront them.

The public misconceptions are clear from YouGov’s latest survey for Prospect. Most voters vastly overstate the amount that is spent on benefits for the unemployed, the level of fraud, the degree of “welfare tourism” by immigrants and the proportion of people who lose their jobs and go on to claim jobseeker’s allowance for more than a year.

According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, crunching data from the Office for National Statistics, Britain’s total welfare bill in 2013/14 was £205bn. This is almost a third of all government spending, and as much as it raises from income tax and corporation tax combined. By far the biggest component is state pensions. Together with pension credit, the total comes to £90bn. Benefits for families with children (mainly child benefit and child tax credit) total £37bn a year. Almost as much, £36bn, goes to sick and disabled people. A further £34bn helps people on low incomes; two-thirds of that takes the form of housing benefit.

By far the smallest category comprises benefits for unemployed men and women: just £4.5bn at the latest count, or a mere 2 per cent of all welfare spending—a far cry from the 34 per cent believed by the average voter.

As for fraud, if the average in our poll, 22 per cent, were correct, then more than £40bn would be received each year by people fiddling the system. The Department of Work and Pensions’ latest estimate is that £3.4bn is wrongly paid—but that most of this is due to “official error.” Only £1.2bn is the result of fraud. That is still £1.2bn too much. It’s a tidy sum that could be spent on other things. But it’s nowhere near the public’s estimate.

Likewise with “welfare tourism.” There is no official figure for the amount of jobseeker’s allowance, housing benefit, child benefit and child tax credits that are currently being claimed by people who have come to Britain in the past 10 years. But the total cost of all these benefits is £76bn, or 37 per cent of the total. Recent immigrants comprise no more than 5 per cent of the population; academic studies indicate that they are less likely than British-born people to receive welfare benefits. This implies a total “welfare tourism” bill of 2 per cent of the £205bn total—possibly less, and certainly no more than 3 per cent. That compares with the public perception, which averages a whopping 23 per cent. Once again, this is not to justify the present state of affairs, just to put it into context.

Nor can these figures be explained simply by the way most people misjudge the relative expenditure on pensions and other welfare benefits. Last autumn, YouGov asked how many of the two million or so immigrants from the rest of the European Union were claiming jobseeker’s allowance. The true figure is around 60,000. The median answer in our survey was 300,000—rising to half a million among UK Independence Party voters.

This is one of the issues at the heart of the Conservatives’ plans to renegotiate Britain’s relationship with the 27 other countries in the EU. Should we have the right to tell people thinking of coming here that they won’t be able to go on the dole, at least for some time? The moral case can certainly be argued. Perhaps people should not be able to claim money from the government unless or until they have paid something in first. But if anyone expects such a measure to make a noticeable difference to Britain’s welfare bill or the number of people settling in Britain, they will be gravely disappointed.

When it comes to long-term unemployment, ministers deplore the “lifestyle choice” of people who manage to continue claiming unemployment benefits for the long-term when they could have a job. Around 100,000 people a month lose their jobs. We asked respondents to estimate the percentage of new claimants who go on to receive jobseeker’s allowance for more than a year. The public’s average estimate is 38 per cent; the actual figure is 10 per cent.

That 10 per cent then needs to be divided into those who genuinely can’t get a job and those who could if they tried, but manage to fool local benefits officials into believing otherwise. By definition, no such figure exists. But as unemployment benefits in total comprise just 2 per cent of all welfare spending, only a fraction of 1 per cent can be attributed to long-term, “lifestyle choice” scroungers.

Explore the data:

The public’s misconceptions about welfare colour their views of the overall impact of the system. Fully 57 per cent believe that it “has created a culture of dependency.” This is closely linked to the views about specific measures. The more people exaggerate the degree of fraud or long-term unemployment, the more likely they are to blame a culture of dependency, and the more they blame the system as a whole for being too generous. Of those who endorse the “dependency culture” thesis, fully 66 per cent say that our benefits system is too generous. Among the 30 per cent who believe that “most people who rely on welfare benefits are victims of circumstances beyond their control,” only 5 per cent say the system is too generous.

As might be expected, people who blame the “culture of dependency” are more likely than the rest of the public to overstate the amount of money going to fraudsters, immigrants and the jobless. However, the difference is not huge: even people who embrace the “circumstance” view of welfare also tend to overstate the money spent in these politically sensitive areas. It looks as if the devotion of the media to stories of welfare “abuse,” and of politicians to promising to address such abuses, has shaped the perceptions of the vast majority of voters—even those who are on the side of claimants or are, indeed, recipients of welfare benefits themselves—not least the biggest group of beneficiaries: the elderly. Among the small minority who broadly understand how our welfare spending is shared out, few think the system is too generous or generates a culture of dependency.

"However you carve it up, the interaction of rising life expectancy (hooray) with our frighteningly expensive national welfare bill (oh dear) means that for big savings we need to look to the elderly, not scroungers, fraudsters or immigrants"

I doubt if any minister would admit to welcoming, far less encouraging, the public misconceptions that we have uncovered. However, they have benefited from it. There is strong public support for a number of the measures they have advanced since 2010, such as capping the total amount of benefits that any one household can receive at £26,000 a year, and banning immigrants from receiving benefits until they have lived here for at least two years. The only measures that have been floated that do not meet public approval are curbing the access of young adults to benefits. Just 15 per cent would scrap all benefits to the under 25s, while a higher number, though still a minority, 38 per cent, would force them to live with their parents (or someone else willing to give them free accommodation).

As for means-testing older people so that well-off pensioners stop receiving winter fuel allowance and other universal benefits, the public divides 56-34 per cent in favour; but the over-60s are rather less enthusiastic. Ed Miliband supports a curb on winter fuel payments for richer pensioners, but it’s a moot point whether this will do Labour much good. This is because the people who would feel most strongly are precisely those who would lose out, who happen to be the people who are most determined to vote. And it would save only £200m at most, or 0.1 per cent of the total welfare bill. The larger truth is that none of the “popular” welfare reform measures would make much of a dent in the £205bn welfare bill. However strong the moral case for them, they would have little impact on the nation’s finances. In the long run, by far the biggest savings are likely to come from raising the age at which workers qualify for a state pension.

Explore the data:

The current plans are to raise the age to 66 in 2020, and to 67 by 2028. My guess is that the process will have to be accelerated. I would advise anyone under 40 to plan to work until they are at least 70 before expecting a state pension—and, if they enjoy above-average incomes, to assume that they will receive little from the government, for the means-testing of state pensions must be one of the options that a future government will almost certainly have to consider.

There is a more radical alternative: change the savings-and-pensions system completely so that people have more choice over, and take more responsibility for, the way they save for their retirement—subject to a statutory minimum. This could reduce the welfare bill to taxpayers significantly, albeit at the cost of requiring workers to save more of their salary.

But however you carve it up, the interaction of rising life expectancy (hooray) with our frighteningly expensive national welfare bill (oh dear) means that for big savings we need to look to the elderly, not scroungers, fraudsters or immigrants. And this means politicians taking on a growing, high-turnout and popular section of the electorate, and to stop pretending that going after the easy and unpopular targets will make much of a difference.

I would go further, for the public’s views about welfare reflect a wider mismatch between belief and reality. Surveys find consistently that people think things are worse than they are. Two of the great social advances of the past 10 or 20 years have been the marked reduction in crime and the sharp fall in the number of teenage pregnancies. Yet when people are asked about these things, most say they are bad and getting worse.

Likewise with living standards. We believe that they are no better than a generation ago when in fact we are, on average, more than 50 per cent better off. Today’s Britain has many problems but compared with, say, the 1980s, we are richer (especially pensioners), live longer, make fewer unwanted babies, endure fewer muggings and burglaries, smoke less, have access to far more and cheaper information and entertainment, are better educated, celebrate a far wider variety of cultures and lifestyles, breathe less polluted air, enjoy cleaner beaches and suffer less infant mortality and child poverty. Yet when Ukip comes along and demands a return to the Britain of yesteryear, many of us say “yes please.”

Even more alarmingly, we think our children will not be as prosperous as us when they reach our age. This goes beyond the perfectly reasonable view that we are struggling to recover from recession. When we ask people specifically to look beyond the next few years and consider the long-term future, they remain pessimistic.

Unless the world is afflicted by something terrible to do with war, terrorism or sudden climate change, such pessimism is surely unwarranted. Over the long term, growth is a result of human ingenuity, technical advances and more-or-less open markets. These things are unlikely to disappear, even if we have to put up with greedy banks, dishonest business leaders, unjustified monopolies and incompetent politicians.

Maybe we must simply live with this pervasive bias towards gloom. The trouble is, it distorts our politics. In this spring’s election campaign, politicians from all the main parties (Ukip is not alone in this) will offer solutions to problems of the public’s imagination, rather than confront misconceptions and offer voters an alternative narrative about the state of Britain today.

How refreshing it would be for at least one party to say that most things are actually getting better, and that we should fret less about “welfare tourists” who are rare, claimant fraudsters who don’t cost us much, crime which is falling and pensioners who have never had it so good. Instead we should devote our energies to tackling the real problems we face, such as too few affordable homes and proper apprenticeships, and too many privately-educated white men in top jobs. (Yes, I know every party says it wants to put these things right—but they give them a lower priority than policies designed to stroke the electorate’s prejudices.)

Welfare reform sits squarely on this fault-line between myth and reality. It sets every major party a stern test: to state honestly that the things most people want will save little money—and that to save big bucks we need a radical rethink of the benefits going to pensioners today and in the future. On their current performance it is a test of both political morality and national economics that every major party will duck.

Explore the data: