Now read Peter Kellner on the likelihood of Brexit

There is a paradox at the heart of the new “Völkerwanderung,” the mass movement into Europe of people from all over North Africa, the Middle East and South Asia. From the outside Europe looks alluringly beautiful. But from the inside it is ugly, like one of those grand old Prussian or Polish manor houses that were turned into shabby workers’ sanitoriums under the communists.

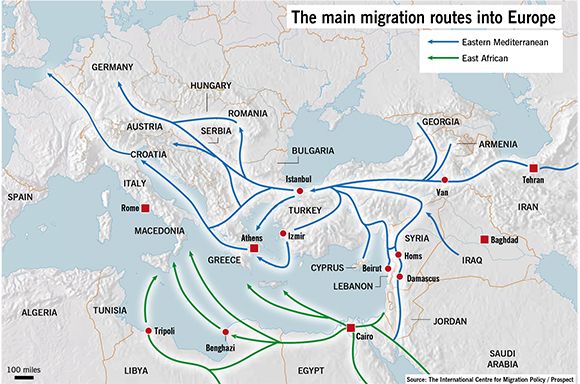

The great migration of 2015 makes it clear that the European Union (EU) is an attractive destination for hundreds of thousands, and probably millions of people. It is so attractive that since January this year, 2,600 people have died crossing the Mediterranean trying to enter the EU. Yet, viewed from the inside, Europe looks a mess. The European economy seems much closer to “secular stagnation”—in Larry Summers’s phrase—than the United States economy. European politics is also in disarray. In almost every member state there is at least one populist party, and nearly all of them are deeply hostile to immigration.

No doubt, many forms of euroscepticism are unpleasant. But that is not to say that euroscepticism is all unwarranted.

Institutionally, European integration is an incomplete project, and perhaps one that will never now be completed. There is a confederation, the EU, which has a monetary union at its core, but not all the members of the EU are members of the eurozone, just as not all EU members have signed up for the supposedly borderless Schengen Area. The UK is now preparing to hold a referendum on whether or not to leave the EU altogether. When one of the biggest economies in the EU is at least contemplating exit, it is fair to say that the project of European unity is not merely incomplete but in jeopardy.

The near death of the euro between 2011 and 2013 has revealed something very important: the critics of the original design of the European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) were right about the fundamental mismatch between countries sharing a single currency yet running separate fiscal policies; taxing, spending and borrowing with only a figleaf of restraint (the 1998 Stability and Growth Pact, largely honoured in the breach). In 2000, Laurence Kotlikoff and I predicted that Europe’s monetary union would degenerate and that this would happen because there was a fundamental incompatibility between creating a monetary union and leaving the member states to do their own thing in fiscal policy.

We claimed that this would work for about ten years, and then fiscal imbalances would cause the whole thing to come apart. That very nearly happened in 2012, when the enormous disparities in public debt came close to destroying the eurozone. Four governments required bailouts. Cyprus and later Greece were able to stay only by imposing capital controls. Today, the possibility of “Grexit” is still discussed; it remains unclear whether or not a solution to the crisis in Greek public finances can be found that will allow Greece to remain inside the euro.

Of course, the fiscal imbalances we foresaw were merely symptoms of deeper structural problems that monetary union had done nothing to address and in some respects had masked. The reason for the swift fiscal deterioration of the so-called PIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Greece and Spain) was that on the eve of the financial crisis their banks were a disaster waiting to happen: over-exposed to frothy real estate, woefully lacking in the capital necessary to absorb the coming losses. The reason the crisis led to much higher unemployment in peripheral countries was that, without anyone quite noticing, they had been falling behind Germany in terms of unit labour costs. When the going got tough, the least competitive firms were disproportionately in southern Europe. Before monetary union, these differentials would have been dealt with through exchange rate changes, with the PIGS’ currencies plunging relative to the German. Under monetary union that was not possible.

Now we have, as a purported solution to these deep-seated problems, a “fiscal compact” signed by every one except the Czechs and the British in 2012. In essence, this requires all members of the euro area to become more like Germany in economic terms. What does that mean? First, it means that they all have to run more or less balanced budgets, so no more of those enormous deficits that we saw in the period of economic crisis after 2008. Formally, the maximum for a deficit will still be 3 per cent, but the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects that by 2020 only one country in the EMU—Slovenia—will have a deficit bigger than 1.5 per cent of GDP. Seven member states will actually be running budget surpluses.

This is the first step in the direction of what Angela Merkel has called the “Bundesrepublik Europa,” the Federal Republic of Europe: an EU that looks more like the Federal Republic of Germany, at least in the way that it handles its public finances; no big deficits and a more or less permanently balanced budget. But it is not the only way that Europe is becoming more like Germany. In the past, member states sometimes ran quite large current account deficits, the gap between the value of their imports of goods and services and the value of their exports. Those days are gone. Partly as a result of doing what is often described disparagingly as “austerity.” Fewer eurozone member states now have current account deficits, for the simple reason that their demand for imports has been squeezed and the competitiveness of their exports has been increased. The IMF projects that by 2020 only three members of the eurozone will have current account deficits, and small ones at that.

Everybody, it seems, is going to have low, maybe even negative inflation if they want to be part of the Bundesrepublik Europa. This year, Austria will be the member state with the highest inflation rate and that will be just 1.1 per cent per annum, according to the IMF. Five countries inside the eurozone now actually have negative inflation rates.

These are the economic consequences of solving the problem of fiscal imbalance and leaving individual countries to regain competitiveness by driving down wages and or raising productivity. The big question is whether this solution is going to be conducive to economic growth and the creation of jobs. The answer seems to be that it will, but only if this policy is mitigated by the European Central Bank’s (ECB) belated adoption of quantitative easing (QE).

What exactly does quantitative easing mean? Some naive critics say that it just means printing money, but that is not quite true, or at least it involves the creation of a special kind of money: not the money you or I are able to carry around in our pockets or keep in bank accounts, but the money that banks can keep in their accounts at the central bank. These reserves are what is created when the ECB undertakes QE, and when it creates this new money, it buys bonds.

What is the effect of QE? It seems to be to drive down already low interest rates, reducing borrowing costs and the returns on safe investments. A side effect is to expand the balance sheet of the central bank, that is, the sum total of bonds and other assets held by the bank. That was no bad thing if only because the balance sheet of the ECB had been shrinking, while the Bank of England’s and the Federal Reserve’s had been growing in the aftermath of the financial crisis. When the ECB adopted quantitative easing it was essentially playing catch up, adopting an unconventional monetary policy that had already been taken on by the other major central banks of the developed world.

Now, one thing is clear: quantitative easing is not about to cause runaway inflation. The real question is whether or not it can suffice to avoid runaway deflation and on that question the jury is still out. Low nominal rates and positive inflation rates mean lower real rates on all that debt Europeans have accumulated. QE also boosts share prices by encouraging investors to hold riskier investments that offer higher returns than low-yielding bonds.

The problem is that it is not yet clear whether quantitative easing combined with fiscal austerity is going to produce much in the way of growth. It is growth that matters for ordinary Europeans, because without that it is highly unlikely that Europe is going to be able to solve its chronic problem of unemployment, and particularly youth unemployment, much less to absorb hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of refugees from the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia.

As far as growth is concerned, there is no question that Europe is underperforming. The IMF is currently predicting that the EU as a whole will grow by just 1.8 per cent this year. Even more worrying, it does not expect that rate to go above 2 per cent before 2020. So, for the foreseeable future, Europe is in low growth mode, which means that unemployment rates, which are still extremely high on the periphery of the EU, are likely to stay high. Unemployment currently ranges from below 5 per cent in Germany, the lowest, to 23 per cent in Spain.

Read more on Europe:

What does Europe want on immigration?

EU Referendum: advantage Cameron

The unemployment data require close scrutiny. As is well known, there is a problem of youth unemployment, particularly in the southern European countries. But equally important is the differential in unemployment rates between native-born Europeans and those born abroad. In the US, it should be noted, foreign-born workers are not significantly more likely to be unemployed than native-born ones. That is also more or less true of the UK. But on the European continent foreign-born workers are much more likely to be unemployed than people born in the country in question. Take Germany, where the unemployment rate for foreign-born workers is 74 per cent higher than for everyone else, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, or Sweden, where immigrants are two and a half times more likely to be unemployed. That is a serious problem. If a society cannot offer employment prospects to immigrants—and if this also applies to the children of immigrants and even their children, as it frequently does—then it is highly likely to fail at one of the most important things a modern society has to be able to do: to assimilate or integrate newcomers.

What does this mean in the great historical scheme of things? Europe is not quite stagnating, but it is certainly not growing dynamically. It is failing to create jobs, and it is failing especially to create jobs for young people and for immigrants. Seen in a broad historical perspective, this suggests that the great shift from the west to the rest is continuing apace. As I argued in my book Civilization: the West and the Rest, this is the biggest economic change the world has seen in 500 years.

If, 500 years ago, you had gone on a world tour, you would not have been especially struck by western Europe compared with some of the other great civilisations you could have visited. It would not have been obvious to a traveller that over the next five centuries there would be a huge divergence in living standards between Europe and the rest of the world. Five hundred years ago, Ming China was in many ways the most sophisticated civilisation in the world. It certainly had some of the biggest cities. Nanjing or Beijing, for example, were far larger than Paris or London. Between the 1600s and the 1970s, a great divergence occurred that saw living standards, on almost any conceivable measure, improve dramatically in western Europe and in places where western Europeans settled in large numbers, notably North America, relative to living standards in China and the rest of the world. This great divergence is the most striking feature of modern history.

The great empires that emerged from Europe together dominated the world’s political landscape (and seascape) as well as its economy. They may have accounted for a minority of the world’s population, but those European empires controlled a huge proportion of the rest of the world’s people.

In our lifetime, however, the great divergence stopped and went into reverse. Back in the late 1970s, when the People’s Republic of China first began to reintroduce market forces into the planned economy, its GDP was a small percentage of the world’s total: around 2 per cent. But last year China’s GDP (adjusted for differences in domestic purchasing power) exceeded that of the United States at more than 16 per cent of total global output.

Part of what we are seeing today is the belated adoption by the rest of the world of ideas and institutions that worked really well for Europe and the west. That is a cause for celebration. It can only be good news that increasing numbers of Asians and now Africans, too, are leaving poverty behind and discovering the benefits of these western institutions and ideas. They still have a long way to go (think about the lack of rule of law in China today, to give just one example), but they have covered an astonishing distance since the 1970s.

The bad news is that even as the rest of the world is getting better institutionally, we in Europe and the west appear to be getting worse. We are suffering from a strange institutional degeneration. This has four aspects.

The first is generational, in the sense that policies in nearly all European states are set to create enormous imbalances between the generations. The way welfare states and pension systems work, in the context of an ageing population, is bound to create burdens for the next generation that they will have to shoulder in order to finance our retirements. The Baby Boomers are leaving the workplace, putting their feet up and looking forward to a long and cushy retirement. But who is going to pay? The answer is: their children, their grandchildren and their great grandchildren.

By the middle of this century the population aged 65 or over in Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain will be one third of the total. In Hungary, by the end of this century, one in 10 people is projected by the United Nations to be 80 or older. This huge demographic shift, which has its roots in changing patterns of fertility and mortality, is making Europe an old and ageing society. But we are still equipped with welfare states that were designed in the postwar period for more youthful societies, with relatively large proportions of the population in education and employment. Either we fix these systems, or a shrinking cohort of young people are going to be shouldering a rising burden of taxation to support the entitlements of the elderly. Sadly, those who argue that the problem can be solved by opening Europe’s borders to millions of immigrants from the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia are making a grave mistake.

The second way in which we are degenerating as a society is through excessive regulation of the economy. In the EU, bureaucrats like nothing better than to draw up enormously complicated directives and impose them on the rest of us. We all have our favourite examples of absurd regulations devised by Eurocrats to govern the size of bananas or the minimum distance that must separate a wall from a newly planted tree (1.4 metres). But the problem is rather more serious than such silliness suggests. Since the financial crisis of 2008, the idea has taken root that the crash happened because of deregulation. As a result, the bureaucrats reason that we now need regulation, and plenty of it, to prevent another crisis from occurring. The great Viennese satirist, Karl Kraus, once remarked that psychoanalysis was the disease of which it pretended to be the cure. The same may be true of regulation. The more we regulate our financial system, ironically, the more complex and therefore unstable it becomes. The lesson has not yet sunk in that it was the most regulated entities in the financial system—banks—that were at the epicentre of the financial crisis.

Third, the rule of law is something less good when it becomes the rule of lawyers, and regulation, in all its complexity, is a gravy train for lawyers. The one part of every business that is rapidly expanding at the moment in Europe and the US is the compliance department, staffed by people with law degrees.

Fourth, and finally, I think we see a degeneration of the institutions of civil society. By civil society I mean the voluntary non-governmental agencies that used to do so much in western civilisation, and which today have largely been marginalised by the ever-expanding public sector, the all-powerful state.

There are a number of remedies for the institutional degeneration of the west as I have described it. You can, for example, improve public financial accounting to end the phenomenon of vast off-balance-sheet liabilities. You can introduce “sunset” clauses for laws and regulations so that they expire rather than accumulate. You can reform legal systems, simplifying the laws as well as the regulations. You can encourage a revival of civil society, for example by expanding private education and promoting competition between schools and colleges.

If the US were to undertake these and other basic institutional reforms, I believe they would suffice to boost American economic growth as well as the health of the country’s social and political life. Europe, too, would benefit from institutional reforms, not least because they would do a great deal more than a crude fiscal compact to reduce the enormous differentials in the quality of governance that exist between member states. To give a single example: according to the World Economic Forum’s 2014 Global Competitiveness survey, Finland leads the world when it comes to the efficiency of its legal system in dealing with cases involving the government. Germany comes 13th. Italy comes 131st.

Radical Islam is the ideological epidemic of our time, just as Bolshevism was an ideological epidemic a century ago. Islamic extremism now represents a global threat to western civilisation. It is capable of threatening lives from Garland, Texas, to Sydney, Australia, but the geographical proximity of the Middle East and North Africa means that it poses a more direct threat to Europe than to other western states.

The threat manifests itself in at least four ways. First, the spread of Islamic extremism within European societies in established immigrant communities like Pakistanis in England, Somalis in the Netherlands, Turks in Germany. A key role has been played here by radical preachers in mosques and Muslim centres funded wholly or partially with money from Gulf states, principally Saudi Arabia. Second, the contamination of non-Muslim communities by extremist proselytising and conversion. Third, the penetration of European countries by new extremists arriving in the guise of asylum seekers, and finally, the two-way traffic between Europe and countries like Syria, Iraq and Pakistan, which enables radicalised young European Muslims to gain experience of conflict and terrorism. It is an astonishing fact that up to 4,500 Europeans have left the EU to join Islamic State in Iraq and in Syria; opting to join a self-styled new caliphate in a misguided and murderous attempt to turn the clock back to the times of the prophet Muhammad’s immediate successors.

Europeans were not sorry to see the back of President George W Bush. They repudiated those leaders, such as Tony Blair, who had supported America’s post-9/11 “war on terror.” They welcomed Barack Obama’s withdrawal of American forces from Iraq and Afghanistan. They shared the naïve view that the “Arab Spring” was a benign phenomenon that would replace dictators with democracies, and they continued to cut their defence budgets so far that Europe has never in its modern history allocated such a small share of national income to the military.

So complete has the abdication of responsibility been that many Europeans find it extremely difficult even to acknowledge the causal connection between the breakdown of states like Iraq, Libya and Syria and the wave of migration that broke over Europe this year. In the outpouring of empathy awoken by the plight of the refugees, I detected almost no recognition that leaving these countries to descend into civil war and anarchy might have been an even bigger mistake than intervening and attempting to democratise Iraq and Afghanistan.

What will be the consequences if a million or more people arrive in Germany this year? Such figures compare to a total asylum intake of 4.1m in the 61 years between 1953 and 2014. The current inflow already exceeds the exodus of citizens of the former German Democratic Republic to the Federal Republic between 1989 and 1990, as a result of German reunification, which totalled almost 600,000. The last time people were flowing into western Europe in their millions was in the aftermath of the Second World War. The defeat of Nazi Germany and its allies led to the displacement of an estimated 25m people. By the end of 1945, over six million refugees had been repatriated by the Allied military forces and UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. By 1947, however, 850,000 displaced persons remained in camps all over Europe, most of them of east European origin.

To set the current migration to Germany into perspective, it is worth remembering that between six and seven million ethnic Germans were expelled from Eastern Europe and territory annexed from the German Reich between 1944 and 1946. The overwhelming majority of those expelled settled in what became the Federal Republic. However, the expellees—like those who crossed from East to West after the fall of the Berlin Wall—were Germans. Today’s newcomers to Germany are (if the official statistics for August are taken as a sample) predominantly from the following countries: Syria (30 per cent); Albania (25 per cent); Afghanistan (7 per cent); and Iraq (5 per cent). They are overwhelmingly Muslim in religion.

In that sense, the relevant parallel is the “Gastarbeiter” programme of the 1960s, which, in over slightly more than a decade (1961-73), saw a total of 2.6m workers arrive in Germany for what was supposed to be temporary employment in its booming industries. Although initially intended to recruit other Europeans, the programme was extended to Turkey. Within a short time, Turks became the most numerous “guest workers” in the country. When the programme was terminated in the economic hard times of 1973, the majority stayed. Today, as a consequence, the number of German residents with origins in Turkey (that is, at least one Turkish parent) is around three million (according to the 2011 census) or approximately 3.7 per cent of Germany’s population.

To say that Germans are ambivalent about their country’s transformation into an “immigration land” with a substantial Muslim minority would be an understatement. Speaking to an audience of young members of the Christian Democratic Union in October 2010, Merkel herself said: “We kidded ourselves a while, we said: ‘They won’t stay, sometime they will be gone,’ but this isn’t reality... and of course the approach [to build] a multicultural [society] and to live side-by-side and to enjoy each other... has failed, utterly failed.” As recently as 2010, the situation in Muslim “parallel societies” in the country became the subject of heated political discussions following the publication of Thilo Sarrazin’s best-selling book Germany Abolishes Itself.

Some recent academic and sub-academic research on the effects of migration underplays the negative effects of large-scale inflows of population and posits modest benefits. There is also a widely believed argument that, because Germany’s population is forecast to shrink as well as to age, the newcomers might actually constitute the answer to the country’s demographic prayers. Yet, as we have already seen, foreign-born unemployment is far higher than native-born unemployment in Germany. And the figures are even worse for countries that have taken relatively large numbers of asylum seekers in the past, notably the Scandinavian countries.

There are, as I have said, things that western states can do to arrest their own institutional degeneration. But I do not believe that institutional reforms alone will suffice to solve the fundamental imbalances that we see today: the imbalance between an ageing Europe and a youthful Muslim world; the imbalance between a post-Christian Europe—secularised and unbelieving—and an increasingly devout Muslim world; the imbalance between a fundamentally safe and just Europe and a dangerous, lawless Muslim word; above all, the imbalance between a Europe that is failing to create sufficient employment even for its own relatively well educated inhabitants and a poorly educated Muslim world, to whom even the benefits paid to asylum claimants represent an improvement in living standards.

Perhaps the solutions to the challenges that we face—from public financial overstretch to the challenges of mass immigration—may come from new technology. Perhaps. But technology alone cannot be relied upon to save us. The early 20th century saw staggering technological advances, much greater than those in our time (compare Twitter with the jet engine). Yet they did not innoculate Europe against fascism and communism. Nor did they prevent the vast displacements of population and redrawing of borders that those ideologies ultimately caused.

My final question is a stark one: is Europe today any better equipped to withstand the new ideological plague of Islamic extremism, and all that follows in its wake, not least the inevitable populist backlash? In the absence of radical institutional reform to reverse the great degeneration, and without a revival of belief in the values of western civilisation itself, I doubt it. From the outside, Europe may continue to look attractive. But on the inside I fear it is only going to get uglier.

There is a paradox at the heart of the new “Völkerwanderung,” the mass movement into Europe of people from all over North Africa, the Middle East and South Asia. From the outside Europe looks alluringly beautiful. But from the inside it is ugly, like one of those grand old Prussian or Polish manor houses that were turned into shabby workers’ sanitoriums under the communists.

The great migration of 2015 makes it clear that the European Union (EU) is an attractive destination for hundreds of thousands, and probably millions of people. It is so attractive that since January this year, 2,600 people have died crossing the Mediterranean trying to enter the EU. Yet, viewed from the inside, Europe looks a mess. The European economy seems much closer to “secular stagnation”—in Larry Summers’s phrase—than the United States economy. European politics is also in disarray. In almost every member state there is at least one populist party, and nearly all of them are deeply hostile to immigration.

No doubt, many forms of euroscepticism are unpleasant. But that is not to say that euroscepticism is all unwarranted.

Institutionally, European integration is an incomplete project, and perhaps one that will never now be completed. There is a confederation, the EU, which has a monetary union at its core, but not all the members of the EU are members of the eurozone, just as not all EU members have signed up for the supposedly borderless Schengen Area. The UK is now preparing to hold a referendum on whether or not to leave the EU altogether. When one of the biggest economies in the EU is at least contemplating exit, it is fair to say that the project of European unity is not merely incomplete but in jeopardy.

The near death of the euro between 2011 and 2013 has revealed something very important: the critics of the original design of the European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) were right about the fundamental mismatch between countries sharing a single currency yet running separate fiscal policies; taxing, spending and borrowing with only a figleaf of restraint (the 1998 Stability and Growth Pact, largely honoured in the breach). In 2000, Laurence Kotlikoff and I predicted that Europe’s monetary union would degenerate and that this would happen because there was a fundamental incompatibility between creating a monetary union and leaving the member states to do their own thing in fiscal policy.

We claimed that this would work for about ten years, and then fiscal imbalances would cause the whole thing to come apart. That very nearly happened in 2012, when the enormous disparities in public debt came close to destroying the eurozone. Four governments required bailouts. Cyprus and later Greece were able to stay only by imposing capital controls. Today, the possibility of “Grexit” is still discussed; it remains unclear whether or not a solution to the crisis in Greek public finances can be found that will allow Greece to remain inside the euro.

Of course, the fiscal imbalances we foresaw were merely symptoms of deeper structural problems that monetary union had done nothing to address and in some respects had masked. The reason for the swift fiscal deterioration of the so-called PIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Greece and Spain) was that on the eve of the financial crisis their banks were a disaster waiting to happen: over-exposed to frothy real estate, woefully lacking in the capital necessary to absorb the coming losses. The reason the crisis led to much higher unemployment in peripheral countries was that, without anyone quite noticing, they had been falling behind Germany in terms of unit labour costs. When the going got tough, the least competitive firms were disproportionately in southern Europe. Before monetary union, these differentials would have been dealt with through exchange rate changes, with the PIGS’ currencies plunging relative to the German. Under monetary union that was not possible.

Now we have, as a purported solution to these deep-seated problems, a “fiscal compact” signed by every one except the Czechs and the British in 2012. In essence, this requires all members of the euro area to become more like Germany in economic terms. What does that mean? First, it means that they all have to run more or less balanced budgets, so no more of those enormous deficits that we saw in the period of economic crisis after 2008. Formally, the maximum for a deficit will still be 3 per cent, but the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects that by 2020 only one country in the EMU—Slovenia—will have a deficit bigger than 1.5 per cent of GDP. Seven member states will actually be running budget surpluses.

This is the first step in the direction of what Angela Merkel has called the “Bundesrepublik Europa,” the Federal Republic of Europe: an EU that looks more like the Federal Republic of Germany, at least in the way that it handles its public finances; no big deficits and a more or less permanently balanced budget. But it is not the only way that Europe is becoming more like Germany. In the past, member states sometimes ran quite large current account deficits, the gap between the value of their imports of goods and services and the value of their exports. Those days are gone. Partly as a result of doing what is often described disparagingly as “austerity.” Fewer eurozone member states now have current account deficits, for the simple reason that their demand for imports has been squeezed and the competitiveness of their exports has been increased. The IMF projects that by 2020 only three members of the eurozone will have current account deficits, and small ones at that.

Everybody, it seems, is going to have low, maybe even negative inflation if they want to be part of the Bundesrepublik Europa. This year, Austria will be the member state with the highest inflation rate and that will be just 1.1 per cent per annum, according to the IMF. Five countries inside the eurozone now actually have negative inflation rates.

These are the economic consequences of solving the problem of fiscal imbalance and leaving individual countries to regain competitiveness by driving down wages and or raising productivity. The big question is whether this solution is going to be conducive to economic growth and the creation of jobs. The answer seems to be that it will, but only if this policy is mitigated by the European Central Bank’s (ECB) belated adoption of quantitative easing (QE).

What exactly does quantitative easing mean? Some naive critics say that it just means printing money, but that is not quite true, or at least it involves the creation of a special kind of money: not the money you or I are able to carry around in our pockets or keep in bank accounts, but the money that banks can keep in their accounts at the central bank. These reserves are what is created when the ECB undertakes QE, and when it creates this new money, it buys bonds.

What is the effect of QE? It seems to be to drive down already low interest rates, reducing borrowing costs and the returns on safe investments. A side effect is to expand the balance sheet of the central bank, that is, the sum total of bonds and other assets held by the bank. That was no bad thing if only because the balance sheet of the ECB had been shrinking, while the Bank of England’s and the Federal Reserve’s had been growing in the aftermath of the financial crisis. When the ECB adopted quantitative easing it was essentially playing catch up, adopting an unconventional monetary policy that had already been taken on by the other major central banks of the developed world.

Now, one thing is clear: quantitative easing is not about to cause runaway inflation. The real question is whether or not it can suffice to avoid runaway deflation and on that question the jury is still out. Low nominal rates and positive inflation rates mean lower real rates on all that debt Europeans have accumulated. QE also boosts share prices by encouraging investors to hold riskier investments that offer higher returns than low-yielding bonds.

The problem is that it is not yet clear whether quantitative easing combined with fiscal austerity is going to produce much in the way of growth. It is growth that matters for ordinary Europeans, because without that it is highly unlikely that Europe is going to be able to solve its chronic problem of unemployment, and particularly youth unemployment, much less to absorb hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of refugees from the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia.

As far as growth is concerned, there is no question that Europe is underperforming. The IMF is currently predicting that the EU as a whole will grow by just 1.8 per cent this year. Even more worrying, it does not expect that rate to go above 2 per cent before 2020. So, for the foreseeable future, Europe is in low growth mode, which means that unemployment rates, which are still extremely high on the periphery of the EU, are likely to stay high. Unemployment currently ranges from below 5 per cent in Germany, the lowest, to 23 per cent in Spain.

Read more on Europe:

What does Europe want on immigration?

EU Referendum: advantage Cameron

The unemployment data require close scrutiny. As is well known, there is a problem of youth unemployment, particularly in the southern European countries. But equally important is the differential in unemployment rates between native-born Europeans and those born abroad. In the US, it should be noted, foreign-born workers are not significantly more likely to be unemployed than native-born ones. That is also more or less true of the UK. But on the European continent foreign-born workers are much more likely to be unemployed than people born in the country in question. Take Germany, where the unemployment rate for foreign-born workers is 74 per cent higher than for everyone else, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, or Sweden, where immigrants are two and a half times more likely to be unemployed. That is a serious problem. If a society cannot offer employment prospects to immigrants—and if this also applies to the children of immigrants and even their children, as it frequently does—then it is highly likely to fail at one of the most important things a modern society has to be able to do: to assimilate or integrate newcomers.

What does this mean in the great historical scheme of things? Europe is not quite stagnating, but it is certainly not growing dynamically. It is failing to create jobs, and it is failing especially to create jobs for young people and for immigrants. Seen in a broad historical perspective, this suggests that the great shift from the west to the rest is continuing apace. As I argued in my book Civilization: the West and the Rest, this is the biggest economic change the world has seen in 500 years.

If, 500 years ago, you had gone on a world tour, you would not have been especially struck by western Europe compared with some of the other great civilisations you could have visited. It would not have been obvious to a traveller that over the next five centuries there would be a huge divergence in living standards between Europe and the rest of the world. Five hundred years ago, Ming China was in many ways the most sophisticated civilisation in the world. It certainly had some of the biggest cities. Nanjing or Beijing, for example, were far larger than Paris or London. Between the 1600s and the 1970s, a great divergence occurred that saw living standards, on almost any conceivable measure, improve dramatically in western Europe and in places where western Europeans settled in large numbers, notably North America, relative to living standards in China and the rest of the world. This great divergence is the most striking feature of modern history.

The great empires that emerged from Europe together dominated the world’s political landscape (and seascape) as well as its economy. They may have accounted for a minority of the world’s population, but those European empires controlled a huge proportion of the rest of the world’s people.

In our lifetime, however, the great divergence stopped and went into reverse. Back in the late 1970s, when the People’s Republic of China first began to reintroduce market forces into the planned economy, its GDP was a small percentage of the world’s total: around 2 per cent. But last year China’s GDP (adjusted for differences in domestic purchasing power) exceeded that of the United States at more than 16 per cent of total global output.

"Part of what we are seeing today is the belated adoption by the rest of the world of ideas and institutions that worked really well for Europe and the west"What has driven this shift? One answer to that question is a good news story, the other a not-so-good news story. The good news is that China and other countries have adopted the things that after 1500 made Europe so successful. First, was the idea of competition in economic as well as in political life. Second, the notion of science that underpinned the scientific revolution of the 17th and 18th centuries. Third, was the notion of the rule of law based on private property rights. Fourth, modern medicine, the branch of the scientific revolution that doubled and then more than doubled life expectancy. Fifth, was the consumer society, and sixth, the work ethic.

Part of what we are seeing today is the belated adoption by the rest of the world of ideas and institutions that worked really well for Europe and the west. That is a cause for celebration. It can only be good news that increasing numbers of Asians and now Africans, too, are leaving poverty behind and discovering the benefits of these western institutions and ideas. They still have a long way to go (think about the lack of rule of law in China today, to give just one example), but they have covered an astonishing distance since the 1970s.

The bad news is that even as the rest of the world is getting better institutionally, we in Europe and the west appear to be getting worse. We are suffering from a strange institutional degeneration. This has four aspects.

The first is generational, in the sense that policies in nearly all European states are set to create enormous imbalances between the generations. The way welfare states and pension systems work, in the context of an ageing population, is bound to create burdens for the next generation that they will have to shoulder in order to finance our retirements. The Baby Boomers are leaving the workplace, putting their feet up and looking forward to a long and cushy retirement. But who is going to pay? The answer is: their children, their grandchildren and their great grandchildren.

By the middle of this century the population aged 65 or over in Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain will be one third of the total. In Hungary, by the end of this century, one in 10 people is projected by the United Nations to be 80 or older. This huge demographic shift, which has its roots in changing patterns of fertility and mortality, is making Europe an old and ageing society. But we are still equipped with welfare states that were designed in the postwar period for more youthful societies, with relatively large proportions of the population in education and employment. Either we fix these systems, or a shrinking cohort of young people are going to be shouldering a rising burden of taxation to support the entitlements of the elderly. Sadly, those who argue that the problem can be solved by opening Europe’s borders to millions of immigrants from the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia are making a grave mistake.

The second way in which we are degenerating as a society is through excessive regulation of the economy. In the EU, bureaucrats like nothing better than to draw up enormously complicated directives and impose them on the rest of us. We all have our favourite examples of absurd regulations devised by Eurocrats to govern the size of bananas or the minimum distance that must separate a wall from a newly planted tree (1.4 metres). But the problem is rather more serious than such silliness suggests. Since the financial crisis of 2008, the idea has taken root that the crash happened because of deregulation. As a result, the bureaucrats reason that we now need regulation, and plenty of it, to prevent another crisis from occurring. The great Viennese satirist, Karl Kraus, once remarked that psychoanalysis was the disease of which it pretended to be the cure. The same may be true of regulation. The more we regulate our financial system, ironically, the more complex and therefore unstable it becomes. The lesson has not yet sunk in that it was the most regulated entities in the financial system—banks—that were at the epicentre of the financial crisis.

Third, the rule of law is something less good when it becomes the rule of lawyers, and regulation, in all its complexity, is a gravy train for lawyers. The one part of every business that is rapidly expanding at the moment in Europe and the US is the compliance department, staffed by people with law degrees.

Fourth, and finally, I think we see a degeneration of the institutions of civil society. By civil society I mean the voluntary non-governmental agencies that used to do so much in western civilisation, and which today have largely been marginalised by the ever-expanding public sector, the all-powerful state.

There are a number of remedies for the institutional degeneration of the west as I have described it. You can, for example, improve public financial accounting to end the phenomenon of vast off-balance-sheet liabilities. You can introduce “sunset” clauses for laws and regulations so that they expire rather than accumulate. You can reform legal systems, simplifying the laws as well as the regulations. You can encourage a revival of civil society, for example by expanding private education and promoting competition between schools and colleges.

If the US were to undertake these and other basic institutional reforms, I believe they would suffice to boost American economic growth as well as the health of the country’s social and political life. Europe, too, would benefit from institutional reforms, not least because they would do a great deal more than a crude fiscal compact to reduce the enormous differentials in the quality of governance that exist between member states. To give a single example: according to the World Economic Forum’s 2014 Global Competitiveness survey, Finland leads the world when it comes to the efficiency of its legal system in dealing with cases involving the government. Germany comes 13th. Italy comes 131st.

"Radical Islam is the ideological epidemic of our time, just as Bolshevism was an ideological epidemic a century ago"For Europe, however, there is an additional and daunting problem over and above the low quality of south European institutions. As well as the threats from within that I have described, there is also a threat to Europe from outside.

Radical Islam is the ideological epidemic of our time, just as Bolshevism was an ideological epidemic a century ago. Islamic extremism now represents a global threat to western civilisation. It is capable of threatening lives from Garland, Texas, to Sydney, Australia, but the geographical proximity of the Middle East and North Africa means that it poses a more direct threat to Europe than to other western states.

The threat manifests itself in at least four ways. First, the spread of Islamic extremism within European societies in established immigrant communities like Pakistanis in England, Somalis in the Netherlands, Turks in Germany. A key role has been played here by radical preachers in mosques and Muslim centres funded wholly or partially with money from Gulf states, principally Saudi Arabia. Second, the contamination of non-Muslim communities by extremist proselytising and conversion. Third, the penetration of European countries by new extremists arriving in the guise of asylum seekers, and finally, the two-way traffic between Europe and countries like Syria, Iraq and Pakistan, which enables radicalised young European Muslims to gain experience of conflict and terrorism. It is an astonishing fact that up to 4,500 Europeans have left the EU to join Islamic State in Iraq and in Syria; opting to join a self-styled new caliphate in a misguided and murderous attempt to turn the clock back to the times of the prophet Muhammad’s immediate successors.

Europeans were not sorry to see the back of President George W Bush. They repudiated those leaders, such as Tony Blair, who had supported America’s post-9/11 “war on terror.” They welcomed Barack Obama’s withdrawal of American forces from Iraq and Afghanistan. They shared the naïve view that the “Arab Spring” was a benign phenomenon that would replace dictators with democracies, and they continued to cut their defence budgets so far that Europe has never in its modern history allocated such a small share of national income to the military.

So complete has the abdication of responsibility been that many Europeans find it extremely difficult even to acknowledge the causal connection between the breakdown of states like Iraq, Libya and Syria and the wave of migration that broke over Europe this year. In the outpouring of empathy awoken by the plight of the refugees, I detected almost no recognition that leaving these countries to descend into civil war and anarchy might have been an even bigger mistake than intervening and attempting to democratise Iraq and Afghanistan.

What will be the consequences if a million or more people arrive in Germany this year? Such figures compare to a total asylum intake of 4.1m in the 61 years between 1953 and 2014. The current inflow already exceeds the exodus of citizens of the former German Democratic Republic to the Federal Republic between 1989 and 1990, as a result of German reunification, which totalled almost 600,000. The last time people were flowing into western Europe in their millions was in the aftermath of the Second World War. The defeat of Nazi Germany and its allies led to the displacement of an estimated 25m people. By the end of 1945, over six million refugees had been repatriated by the Allied military forces and UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. By 1947, however, 850,000 displaced persons remained in camps all over Europe, most of them of east European origin.

To set the current migration to Germany into perspective, it is worth remembering that between six and seven million ethnic Germans were expelled from Eastern Europe and territory annexed from the German Reich between 1944 and 1946. The overwhelming majority of those expelled settled in what became the Federal Republic. However, the expellees—like those who crossed from East to West after the fall of the Berlin Wall—were Germans. Today’s newcomers to Germany are (if the official statistics for August are taken as a sample) predominantly from the following countries: Syria (30 per cent); Albania (25 per cent); Afghanistan (7 per cent); and Iraq (5 per cent). They are overwhelmingly Muslim in religion.

In that sense, the relevant parallel is the “Gastarbeiter” programme of the 1960s, which, in over slightly more than a decade (1961-73), saw a total of 2.6m workers arrive in Germany for what was supposed to be temporary employment in its booming industries. Although initially intended to recruit other Europeans, the programme was extended to Turkey. Within a short time, Turks became the most numerous “guest workers” in the country. When the programme was terminated in the economic hard times of 1973, the majority stayed. Today, as a consequence, the number of German residents with origins in Turkey (that is, at least one Turkish parent) is around three million (according to the 2011 census) or approximately 3.7 per cent of Germany’s population.

To say that Germans are ambivalent about their country’s transformation into an “immigration land” with a substantial Muslim minority would be an understatement. Speaking to an audience of young members of the Christian Democratic Union in October 2010, Merkel herself said: “We kidded ourselves a while, we said: ‘They won’t stay, sometime they will be gone,’ but this isn’t reality... and of course the approach [to build] a multicultural [society] and to live side-by-side and to enjoy each other... has failed, utterly failed.” As recently as 2010, the situation in Muslim “parallel societies” in the country became the subject of heated political discussions following the publication of Thilo Sarrazin’s best-selling book Germany Abolishes Itself.

Some recent academic and sub-academic research on the effects of migration underplays the negative effects of large-scale inflows of population and posits modest benefits. There is also a widely believed argument that, because Germany’s population is forecast to shrink as well as to age, the newcomers might actually constitute the answer to the country’s demographic prayers. Yet, as we have already seen, foreign-born unemployment is far higher than native-born unemployment in Germany. And the figures are even worse for countries that have taken relatively large numbers of asylum seekers in the past, notably the Scandinavian countries.

There are, as I have said, things that western states can do to arrest their own institutional degeneration. But I do not believe that institutional reforms alone will suffice to solve the fundamental imbalances that we see today: the imbalance between an ageing Europe and a youthful Muslim world; the imbalance between a post-Christian Europe—secularised and unbelieving—and an increasingly devout Muslim world; the imbalance between a fundamentally safe and just Europe and a dangerous, lawless Muslim word; above all, the imbalance between a Europe that is failing to create sufficient employment even for its own relatively well educated inhabitants and a poorly educated Muslim world, to whom even the benefits paid to asylum claimants represent an improvement in living standards.

Perhaps the solutions to the challenges that we face—from public financial overstretch to the challenges of mass immigration—may come from new technology. Perhaps. But technology alone cannot be relied upon to save us. The early 20th century saw staggering technological advances, much greater than those in our time (compare Twitter with the jet engine). Yet they did not innoculate Europe against fascism and communism. Nor did they prevent the vast displacements of population and redrawing of borders that those ideologies ultimately caused.

My final question is a stark one: is Europe today any better equipped to withstand the new ideological plague of Islamic extremism, and all that follows in its wake, not least the inevitable populist backlash? In the absence of radical institutional reform to reverse the great degeneration, and without a revival of belief in the values of western civilisation itself, I doubt it. From the outside, Europe may continue to look attractive. But on the inside I fear it is only going to get uglier.