Approaching Whitechapel Gallery in east London, I can see queue barriers outside the gallery’s frontage. The silver, waist-high pillars are now a familiar sight in the city, marking out entrances, smoking areas, outdoor seating—and curtailing the spontaneity of the walk-in customer. For a small space like Whitechapel, an unplanned visitor is now an inconvenience. I am here on a rainy Sunday to see Radical Figures, the newly reopened exhibition of contemporary paintings.

I’ve booked online, and read that strict social distancing measures will be in place. The most noticeable change in entering the lobby is the mandatory temperature check, run by a single visored staff member. What looks like a small iPad sits tilted on the desk. I quickly revert to passport control mode: shoulders back, straight face, direct stare into the lens. You're doing it wrong, the gallery assistant says. You have to lean right down into the camera, as if approaching a microscope. After a few seconds, it displays 36.4 degrees. The cut-off is 37.3. I have my ticket checked again, and walk ahead into the first room of the exhibition.

The pandemic has forced us to dramatically rethink our approach to public space: to reclassify destinations according to perceived risk, with little concrete knowledge of the virus’s true prevalence. Indoor spaces are friendlier to infection. Space that serve food and drink—and our medical centres—have been deemed essential. Education, exercise and community follow closely behind. The argument for reopening our cultural institutions has been made with force: art sustains us, say the museum executives over the morning airwaves. But when I enter the exhibition, the first thing I wish is that, in the quest for sufficient sustenance, I’d brought a bottle of water—the mask dehydrates you quickly.

The social contract between the visitor and the gallery has changed: risk assessment and behavioural control are now the parameters within which visitor experience is defined. A space of relaxation, leisure and education has become one of intense moral precarity. What does choosing to see art in a time of suffering say about our values? It is not essential, and therefore it is an indulgence. I am putting myself, the staff, their peers and my household at risk; the only defence I have is the desire to be in front of the paintings. Unlike sport or music—which rely on a collective atmosphere created by attendee density—galleries have always operated best as spaces of alluring emptiness—of concentration, breathability and time. We now have that, but it comes at the price of uncertainty.

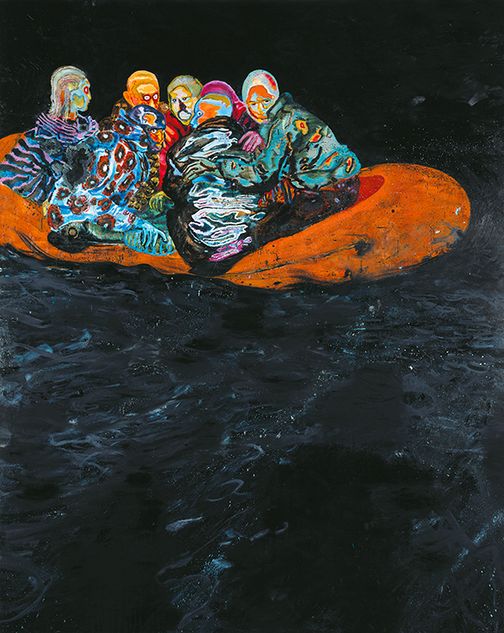

It is not difficult to enjoy the work on show, though it is impossible to be fully transported. Radical Figures, the exhibition I am here to see, showcases work by ten artists who have come to prominence since 2000. Its aim, the gallery claims, is to correct the perception of painting’s “death” after the Neo-Expressionistic boom of the 1980s by displaying work which pushes the boundaries of figurative representation—of bodies in particular. In the main room, Daniel Richter’s Tarifa repurposes an image of a migrant Mediterranean sea crossing with an infrared colour palate. Throughout the exhibition, bodies are rendered with arcing, unfussy lines across canvases; faces are uncomplicated yet expressive. Rarely are subjects presented alone; tactility is central to the works, and bodies are often entwined, in a leaning kiss—as in Michael Armitage’s Kampala Suburb—or in community, such as Tala Madani’s Sitting in White, which satirises group prayer by blending the men's beards into cartoon grins.

![Nicole Eisenman, Progress Real and Imagined [panel i] (2006)](https://media.prospectmagazine.co.uk/prod/images/gm_preview/af7b9396dac2-nicole-eisenman-progress-real-and-imagined-panel-i-20065.jpg)

There are five or six other people in the gallery with me. Everyone is masked, and we avoid each other like repelling magnets. We can’t see each other’s smiles under the face coverings, which creates an air of imagined stand-offishness to add to the physical distancing. There is little affinity, despite us all making the same calculation to visit on a wet Sunday afternoon—and to deem art worth the risk. There is no prescribed route, and I feel guilty doubling back on myself for fear of intercepting another person’s path, so purposely spend a long time in front of each piece. I use the printed programme to guide me through the rooms, paying more attention than usual to the spatial aspects of the curation. In the third room, Nicole Eisenman’s Progress: Real and Imagined dominates. Split into two panels, the first side shows an artist working in a studio onboard a boat, hunched over while the detritus of creation falls and tumbles around them. The second panel resembles an absurdist apocalypse, showing birth, hunting and myriad entwined bodies glowing like embers—it has all the busyness of a Diego Rivera mural, but with parodic elements, like flying hamburgers set against a dusky sky.It feels vaguely comforting to be confronted with this kind of visual strangeness—a distraction from the unreality of the last few months. The exhibition occupies a uniquely transient position: commissioned and curated before the lockdown, but recontextualised for the visiting public in its aftermath. This may never happen again. Art signifying different things as the news unfolds is nothing new, but the sense of upheaval now is so overwhelming and universal that it is impossible to exorcise. In the last room of the exhibition, a canvas by Tschabalala Self achieves the same effect. Her painting of a disproportioned, obtuse-looking NYPD officer, made in 2019, seems to usher us out of the gallery, after months of hanging in an empty room while the outside world redefines him. The viewer’s eyes jump to his black handgun, tight in its holster.

![Nicole Eisenman, Progress Real and Imagined [Panel II] (2006)](https://media.prospectmagazine.co.uk/prod/images/gm_preview/83d9ebe5d9ba-nicole-eisenman-progress-real-and-imagined-panel-ii-20062.jpg)

Exiting the final room, a man ignores the sign to use the lift down to the lobby and walks through a barrier to the free collections. Not every movement can be controlled. That artists, curators and directors will respond to the pandemic in their work is inarguable. Though in a time of crisis, the viewer’s role within perception is heightened. Just by being in the space, visitors are defining its emotional, moral and ethical boundaries. They might see themselves as defiant, sensible, or supportive; in reality, they may be foolish and selfish—even dangerous. But whoever’s advice they are following, and whatever justification they use, they are indeed, for a brief moment, being sustained by art.