At London’s Criterion Theatre, volunteers are awkwardly shuffling on stage. The magician has picked them at random and asked them each to think of a song and tell nobody. She sits at the piano with eyes closed, listening for spirit voices to guide her. Slowly, she begins playing the first few notes: “Today is gonna be the day that they’re gonna throw it back to you…” A delighted volunteer announces that it was indeed his song. For a moment, the audience is captivated: we can’t work out how this trick was managed. “Well, that’s what I wrote down earlier,” the volunteer adds. There’s a ripple of deflation throughout the audience as this rather obvious trick is revealed—the magician had somehow read the volunteer’s piece of paper backstage. It’s not that anyone really thought spirits from the netherworld had come to Leicester Square to sing Oasis’s “Wonderwall”. But, for a few moments, we had at least tried to turn off our reason and suspend disbelief.

Such is our 21st-century relationship with magic. We like—for fleeting moments, in the dark of a theatre—to pretend to believe, though of course we actually don’t. It’s all a bit of a laugh, isn’t it? Our views in this regard were established during the Enlightenment; since which time, people—with the exception of a few notable eccentrics—have set their stall by the natural and provable, rather than the supernatural and false. But things weren’t always like that. For centuries, magic, religion and science were all part of the same firmament. Have we lost anything with magic’s demotion?

In Magus, the American historian and Princeton professor Anthony Grafton describes a world full of faith in the occult. Many Catholics in the Holy Roman Empire feared demonic influence, including Maximilian I, the emperor himself, who wore an enchanted ring—which he called der Teufel (the Devil)—all his life, and tried to use it to improve his finances. In this dense and scholarly work, Grafton charts the history of learned magic in the 16th and 17th centuries through the lives of a few magical scholars, or magi.

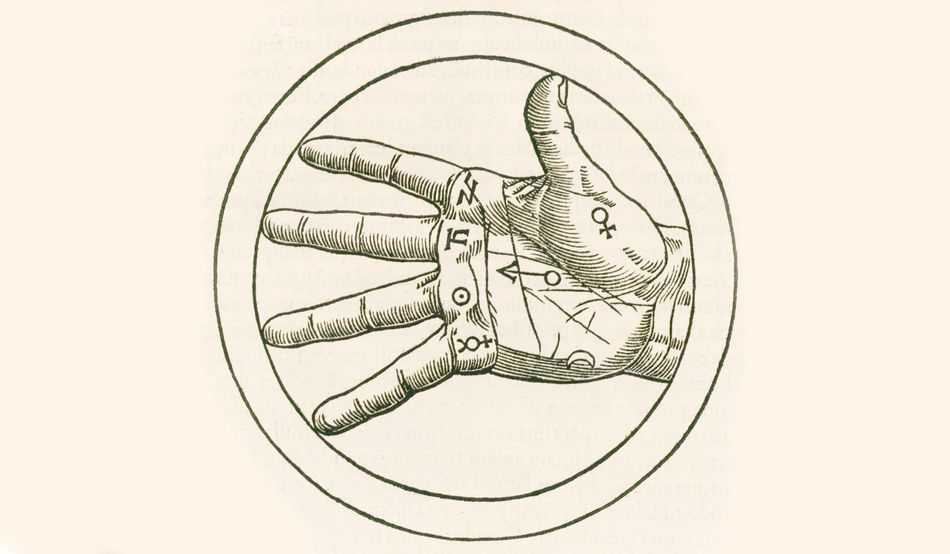

These men argued that they followed the tradition of the three Biblical magi (or wise men) who studied the skies and followed a bright star to Jesus’s cradle. But their studies went well beyond Biblical teaching. Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, whom Grafton calls “the greatest magus of the 16th century”, believed that Earth was “haunted by spirits at every level, from the fauns, lemurs, and hamadryads to be found in the terrestrial world to the angels whose names and seals he listed in vast, hallucinatory charts”.

From the 13th century on, a divide emerged between “low” and “high” magic. “One, classical in origin and densely erudite in texture, regularly attracted the interest of serious philosophers. The other, miscellaneous and diffuse, was chiefly studied and practised at a lower social level,” as Grafton explains. I’ll leave you to figure out which one is which. Naturally, other prejudices influenced which magic was deemed illicit: Jewish people were often accused of performing anti-Christian sorcery, and thousands of women were persecuted for witchcraft—using their eyes to “fascinate” men or working with devils to make men impotent.

Learned magi argued that their studies were compatible with Christianity

For some people, anyone who dabbled in the supernatural—even the most scholarly of magicians—was suspicious. Saint Augustine argued that both “good” and “bad” magic “were bound by the deceptive rites of demons, under the names of angels.” The philosopher and bishop Nicholas of Cusa thought all of it was horrifying. “The forms of divination, which the devil provides, are many,” he declared. “Aeromancy, pyromancy, hydromancy, geomancy and so on... All of this is prohibited.”

Learned magi argued that their studies were compatible with Christianity. Two Florentine scholars, the sedentary and serious Marsilio Ficino and the wild, rash Pico della Mirandola—a pair of unlikely friends who are among the most engaging characters in Magus—argued that good magic was respectful of God’s creation and “did not promise a violent transformation of the natural world but the full realisation of its powers”.

Pico compared himself to nature’s obedient “midwife”: “There is no greater stimulus to religion or to any worship of God than constantly contemplating God’s marvels,” he wrote. “After exploring them carefully through this natural magic of which I speak, we will be stirred to worship their Creator with a hotter passion.” Ficino compared the magus, in general, to a farmer tending nature’s power through rituals such as incantations and incense burning. On Grafton’s account, Ficino envisioned the magus’s role as “spiritual agriculture—the cultivation of the world’s secret energies that wise men had always practised”. Ficino was happy to relinquish his free will, and believed firmly that his life was controlled by the planets and the position of Saturn. One time, he even insisted that Saturn being in retrograde had prevented him from walking to Pico’s house.

Ficino encouraged his fellow magi to live ascetic lifestyles, cautioning “against sex, especially wild sex; eating and drinking too much; and staying up late”. Some of his wellness advice was more questionable. To stop your body going dry and wrinkly after age 70, he wrote, one should “choose a young girl who is healthy, beautiful, cheerful and temperate, and when you are hungry and the Moon is waxing, suck her milk”.

There was plenty of occultist advice to be found elsewhere. Grafton calls Agrippa’s 16th-century study On Occult Philosophy a “desk reference for all learned magicians”. Agrippa instructed readers about how to harness magic in nature; for example, how to use the liquid discharged from mares during sex to make lamps and candles which projected fiendish images of horses’ heads.

He also had tips for what “wonderful things” a magician could do with the body of a red toad. “The small bone that is in its left side, when cast into cold water, makes it immediately become hot,” he wrote. “It restrains the attacks of dogs. Added to a drink, it arouses love and quarrels. When tied to someone, it arouses lust.” The bone on the right side, he cautioned, had opposite traits: it could cool hot water, cure fevers and prevent love and desire. The toad’s spleen and heart, moreover, could make a remedy against poison.

Although Agrippa remained a devout Christian, rumours spread about his diabolic influence. The Jesuit demonologist Martín Del Rio called Agrippa the “Archimagus”, and recorded how he instructed demons to enter a man’s body and kill him. What’s more, Del Rio wrote, Agrippa and his fellow magus Faustus had been known to pay their inn bills with coins that “seemed genuine but turned into bits of horn after a few days”.

Ah, yes, Faustus. The most famous Renaissance magician appears in Grafton’s book not as Christopher Marlowe’s tortured scholar but as a showy, corrupt trickster. Faustus (real name Georg) studied at the University of Heidelberg and became a schoolmaster in Bad Kreuznach—but was fired from his post for “committing sodomy with students”. He travelled from city to city in the Holy Roman Empire, handing out cards advertising himself as “the chief of necromancers, an astrologer, the second magus, a reader of palms, a diviner by earth and fire, second in the art of divination by water”. Although he was often expelled from cities, no one dared punish him further: councillors in Ingolstadt made him swear not to take vengeance on them when he left the city.

Rumours spread of Faustus’s dealings with demons. A scandalised Martin Luther claimed that Faustus called the devil his “brother-in-law”. Another account claimed that he “devoured” a rival magician only to produce him unharmed later, in a cave. And, when Faustus died (by devil strangulation, it was rumoured), his body reportedly kept turning face down on the bier where it lay.

Faustus encouraged his fearsome reputation. One story recounts how, in a rage, he once threatened his dinner host: “One of these days, when you go to the table, I will make all the pots in your kitchen fly out of the chimney, so that you and your guests will have nothing to eat.” When he held a brief academic post at Erfurt, he impressed his pupils by seeming to conjure Homeric characters before them, terrifying them with the Cyclops Polyphemus, who appeared with a man’s legs dangling from his lips.

This last trick, Grafton argues, was perhaps a work of clever craftsmanship: projecting the characters using a lamp and shadows. Much of the sorcery done by Renaissance magicians was inventive in this way. The 15th-century Paduan natural philosopher and inventor Giovanni Fontana explained a way to project “a nocturnal apparition designed to inspire fear”—a devil armed with a sphere—on the wall. He also advised how to make startling automata: birds that appeared to fly and rabbits that could fart fire.

Indeed, Fontana appeared to understand—and perhaps even push forward—the science around our perceptions. He once recorded the case of a mass vision of soldiers on horseback, armed with lances and swords, attacking each other in the clouds above Lombardy. The people below were terrified—not realising, as Fontana did, that these were illusions caused by atmospheric refractions.

Many of the phenomena attributed to supernatural influence were actually a result of human ingenuity

Many of the Renaissance magi were also engineers and inventors. The Benedictine abbot Johannes Trithemius, who was fascinated by the occult, also created a device that could make someone who knew no Latin combine phrases to write perfect Latin sentences. And not everyone was as deferential to nature as Pico and Ficino. The cryptographer Leon Battista Alberti insisted “aggressively… on man’s power over the natural world”. He invented a device with two bronze wheels that created an almost unbreakable code; prefiguring the German Enigma machine in the Second World War, suggests Grafton. Although Alberti understood that the device was a feat of human engineering, he still considered it a secret art, Grafton writes, “like magic”.

Many of the phenomena attributed to supernatural influence were, in fact, a result of human ingenuity. The Cross of Burgos had a figure of Jesus with joints that could move, all covered by leather flaps, and the side emitted animal blood when it was pierced. Even though its technical design was known, priests handled it with “great reverence”, believing it had supernatural qualities, and stories spread of the crucifix speaking and bowing. “Citizens and visitors in Burgos were not fooled when they contemplated the Cross and admired its ability to move,” Grafton notes. “They saw it as both a product of human craft and an object endowed with miraculous powers.”

Similarly, the Rood of Boxley, a crucifix from Boxley Abbey in Kent, had a likeness of Jesus that awed onlookers when it moved its eyes, wept and turned its head. When, upon the dissolution of the monasteries, the cross was removed from the wall, the commissioner found “olde roton stykkes in the backe of the same, that dyd cause the eyes of the same to move and stere in the hede thereof lyke unto a lyvelye thing; and also the nether lippe in lyke wise to move as though itt shulde speke”.

The bishop of Rochester denounced the device in a public sermon. But many of the monks would have been aware of the fakery and had nevertheless decided that it was best kept a secret. Perhaps this was for acclaim, perhaps it was to fortify public faith—in God, but also in magic. After all, isn’t it better to believe that spirits are out there singing “Wonderwall”?