Soon after the discovery of photography in the 1830s, mundane objects captured by the lens—a hairbrush, say, or a china cup—acquired a curious frisson when reproduced on photographic plates. People seeing photographs for the first time wouldn’t regard them as a single integrated view, but rather as details—marvelling at the way, for example, a mason had applied the mortar between the bricks of the house opposite their own. Wolfgang Schivelbusch, the great contemporary theorist of 19th-century mechanisation, puts it thus: “the intensive experience of the sensuous world, terminated by the industrial revolution, underwent a resurrection in the new institution of photography.”

Photography was soon also compensating its enthusiasts for the close-up immediacy annihilated by mechanised transport systems. The train window’s transparency metamorphosed into a magical immateriality, as the passenger ceased to be visually aware of his surroundings, but rather began to view the landscape the train passed through as a series of scenes or staged sets.

If photography supplied the foreground that was robbed by the train, then the train also delivered a huge array of new destinations. During the same period Marx developed his conception of commodities as goods rendered novel and mysterious by the fact of their transportation: imbued, like photographs, with assumptions about their production that turn them into screens; and onto which, in turn, people project their own twisted and exploitative relationships. He dubbed this “fetishism.”

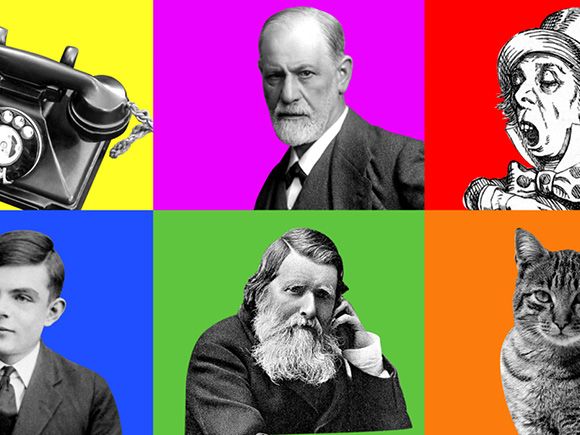

If the train took from us what Ruskin called “an influence, from the silent sky and slumbering fields, more effectual than known or confessed,” the telegraph and the telephone deprived us of those forms of sociality which depended on the presence of others. It’s a truth universally forgotten in our clock-watching era, that when the characters in a Jane Austen novel are expecting company on a given day, they simply wait until the visitors arrive. This imprecision in the time for a rendezvous allowed encounters to be unbounded: conversations expanded into discourses just as luncheon morphed into high tea then dinner. The Mad Hatter’s Tea Party, with its atemporal neuroticism, perfectly exemplifies the later mid-Victorian mood, caught as it was between murderous timekeeping and a neverending teatime.

Concurrent technologies of virtuality and transport are again proving to be reciprocally compensatory in our own pandemic times. In the 15 years between the inception of a fully-integrated bi-directional digital medium—the internet—and the onset of the coronavirus pandemic bringing with it imposed social distancing, viewing the world through screens has become second nature to all of us. The terms of physical meeting have been more profoundly altered than they ever were by train timetables or wristwatches: the absolute location, together with the universal synchronisation afforded by mobile phones, enables both the place and the time of a prospective rendezvous to be continually recalibrated.

“Between the inception of the internet and the onset of the pandemic, viewing the world through screens has become second nature to all of us”

So it was that we learnt to revolve about one another, making continuous course corrections as we homed in—the technology of virtuality reintroducing us to the notion of spontaneity, while depriving us of any possibility of serendipity. Time has been murdered—and Alice never arrives at the tea party because she gets a better invitation en route.

Paired with the curious concatenation of the smartphone, the web and the net, is the curiouser phenomenon of mass air travel. Low-cost airlines begin to clutter up the sky at almost exactly the same time as the inception of mass mobile phone usage—which was also when the world woke up to the problem of global warming. It could be that the compensatory function of virtualising technologies is once again operating here: we’re destroying the natural world we once immediately and sensuously apprehended, while our capacitive touch technology provides us with a simulacrum to pet and prink, swipe and tweezer. Moreover, from the godly perspective of an EasyJet flight to Berlin (and even more so from that of a global positioning satellites on which mobile technology depends), more and more people were able to see that the world was but a grain of sand—or, at any rate, a global-villagey sort of place, in which there were no strangers, only “friends” you’d met on social media.

Since the pandemic began, thrusting entire communities back into their real-world villages, there’s been much talk about what we might call the new mandatory virtuality. Here, too, Schivelbusch’s compensatory dyad seems to be at work: after all, it’s our high-speed mass transit systems that have allowed the virus to spread—while it’s our new technologies of virtualisation that have permitted us to stay (metaphorically) in touch. Very soon after the lockdown began, voices were heard predicting that such was the alacrity and efficiency with which virtual meetings were replacing real ones, the entire mode of doing business—and for that matter education, litigation and all sorts of administration—was going to change forever. The video call was no longer in competition with transportation, but fully asserted itself as the primary locus of human interaction. So long, that is, as your work life doesn’t involve practical—let alone sensuous—engagement with material productive forces.

It’s easy enough to grasp that a series of tedious encounters devised to hierarchically enjoin collective responsibility aren’t significantly impoverished by being virtualised. And if we’re honest, this is what most meetings in large organisations consist of. But how about more intimate ones? The anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss noted in relation to the graphic and plastic arts: “alterations in scale always sacrifice the sensible in favour of the intelligible.” And here we find the internal compensation of virtualisation. In a Zoom meeting or a FaceTime encounter, we discover we must compress the full gamut of interpersonal communication—gesture, body language, pheromones (whether natural or artificial), vocal timbre—into the compass of the screen, and the range of the computer’s mic. My tech-savvy sons (with whom I’ve been enjoying this period of reclusion) point out to me that whenever I’m on a video call I tend to boom louder than a bittern. My performance recalls to mind my own father bellowing into Bakelite telephone receivers when I was a child: “Push Button A!”—a reference to an obsolete phone box operating system—or, in the early 1980s, leaving epistolatory messages on my brand new answerphone: “Dear Will, it’s Dad here…”

“The rise of the virtual has coincided with an increase in mental illness and a decrease in sexual intercourse”

At the time I thought it absurd—but he was merely responding to a novel technology with a mind formed by an old one. All forms of virtuality impoverish our bodily senses, but do video calls also somehow compensate our understanding? JG Ballard’s minatory story “The Intensive Care Unit,” first published in 1977, was uncannily prescient, imagining a world in which all presence is of the tele variety. Its disturbingly reclusive protagonist plans to meet up with his family who live elsewhere and are similarly isolated. He’s only ever seen them on screen before—the children have been conceived using in vitro methods. It’s a murderous rendezvous that begins badly when he and his wife encounter one another for the first time in the real world of his vestibule: “I was struck by her advanced age and, above all, by her small size. For years I had known Margaret as a huge close-up on one or other of the large television screens in the house. Even in long-shot she was usually larger than this hunched and diminutive woman hovering at the end of the hall. It was difficult to believe that I had ever been excited by her empty breasts and narrow thighs.”

Of course, Ballard’s insight that we might prefer our relationships to be more intelligible—and hence controllable—than sensual was hardly original. We can go back to EM Forster’s extraordinary 1909 story The Machine Stops. This visionary work appears to foretell the internet—as well as a society that turns its back on the proximity required by our species for the exchange of bodily fluids, in favour of the exchange of ideas facilitated by the eponymous Machine; one which, in time, comes to enshrine all reality. Forster didn’t anticipate the factoring of sexuality into virtuality, preferring to place a chaste mother-son relationship at the centre of his tale—but of course, our own era has seen virtuality used to provoke tumescence and ejaculation at a distance. In a way, the web complex is purpose-built for pornography—in itself only a sub-species of fetishism.

In this matter, I follow Freud, who identified the active object-oriented fetishes as overwhelmingly male: fearing his own detumescence in the face of the chaotic and uncontrollable organic reality of the Other’s body, the male resorts to a transactional object that’s completely manipulable, whether this be a shoe, a glove, a whip, or a keyboard attached to a computer.

The data is often conflicting, representing all sorts of biases on the part of researchers themselves. Nevertheless, there is considerable evidence to suggest that the rise of the virtual has coincided with both an increase in mental illness—specifically depression, that most ineluctably embodied of states—and a decrease in sexual intercourse. In Japan, some pessimists are suggesting there will be a population decline of as much as 30 per cent by 2040, caused at least in part by the capacity of screen-mediated communication to at once excitingly enlarge the visible body—the “empty breasts and narrow thighs” of Ballard’s disgusted protagonist’s wife—and simultaneously collapse all the stages of becoming intimate with another which were once socially mediated.

Thus if the internet allows simultaneously for the illusion of intimacy and the confusion of pornography with sexual intercourse, it may be placing our species in a sort of embodied zugzwang: compelled towards the other by magnified desire, but constrained by enlarged understanding. And here, perhaps, we find the inversion of the compensatory, as our modes of being in the world join together to displace us from it. Even before the pandemic added our fear of physical contagion to the messy business of touch, people were coming to terms with online dating. You don’t have to be a Marxist to appreciate that apps such as Tinder, Grindr, Zoosk et al first fetishise and then powerfully facilitate—indeed, demand—the commoditisation of our bodies, just as the social media in general do this to ourselves. The business of contemporary dating has to a huge extent moved online—and business is the operative word, because the pixelated panders who own these apps are coining it off our frustrations, sexual and emotional, while we willingly assist them by turning the messy contingencies of our being (our multiplying social selves, our divisible physical ones), into a series of sales pitches.

Men’s tales of online dating often revolve around the disparity between the image and the reality of the other’s body, women’s around the over-intelligibility of men’s behaviour on these sites. Socially embedded male braggadocio, posturing and mansplaining become stereotypic to the point of robotic once compressed to this narrower bandwidth. Writing in the Guardian last December, the novelist CJ Hauser described her purgatorial experiences on Tinder. No fan of small talk, and in search of “Smart Sad People Flaunting Their Intelligence With Panache” (aren’t we all!), Hauser found that the ease of bantering online was matched by the ease of finding herself in a risky situation, having sex with a man who briefly choked her. Driven back to circumspection and attempting to extract concrete information from her computer-mediated interlocutors, she “began seeing similarities between the Turing Test and what us Tinder-searchers were doing—whether we were looking for sex or looking for love.”

The Turing test, named for the computer pioneer—and breaker of the Enigma code—Alan Turing, consists in a verbal examination of another, aimed at establishing whether they are human or an artificial intelligence. Hauser’s imitation of an online Turing testing worked for her in at least one instance—and she had a relationship with a man she met that lasted over a year, and which seems to have given her some pleasure. It also left her with a curious gift: a blanket bestowed upon her by her soon-to-be-ex on their one-year anniversary, that had woven into it their initial Turing testing exchanges on Tinder: the living, breathing man she’d managed to magic out of cyberspace had disappeared back into it, leaving behind only this woolly pelt. You can say what you will about the awkwardness of first dates—or, indeed, all the social contortions by which cultures attempt to mediate their sexual relationships—but at least when you meet someone offline you can be in no doubt about their sentience.

“You don’t have to be a Marxist to appreciate that apps such as Tinder, Grindr, Zoosk et al first fetishise and then powerfully facilitate—indeed, demand—the commoditisation of our bodies”

All of which makes the fantasy of some sort of uninhibited sexual Renaissance, a “contactless sexual revolution”—as hymned by not a few jejune proselytisers—seem sadder and more deluded than just about anything. Ballard’s first-time physically united family members fall upon each other with a murderousness born, surely, of the very realisation that they were… well, once born of each other: theirs is the rage of Calibans forced to the uncomfortable realisation that their bodies aren’t as pristine as machine-code nor their lives as deterministic. His vision stands to remind us of the critical mass of human phenomenology: too close, and we all become Brobdingnagian and revolting to one another—too far, and we become Lilliputians who’ll annihilate one another over the merest abstractions.

My rather pessimistic view of the increasing virtualisation of our lives zooming us towards mass neuroticism in a ghastly mass synergy of fetishism and frigidity isn’t shared by my friend Nick Mercer, an existential psychotherapist. Nick had to shift his practice from the consulting room to the screen this spring, and was initially sceptical about the possibilities for a truly virtual talking therapy: “John Osborne’s verdict on Waiting for Godot came to mind: ‘A very long chew on a very dry prune.’ This, and the pallor of the Greek underworld as I sit squinting in an unnaturally hunched position at the tiny screen of my phone with knotted brow straining to hear the communications of the ghostly figure before me. These delinquent imaginings flourish in the physical absence of the other because these ghostly images lack the power of presence—that total immersion in the physical.”

But two months on, doing 10 hours of therapy a week online, Nick finds himself enchanted by the same prospect: “I’ve seen a whole rich new world open up, one almost unthinkable in the gloom of the old consulting rooms. Heresies abound. A brave new world—and such creatures in it, I muse, as a woman carrying a baby waves to the screen, as she passes through the room and touches my client on the shoulder in gentle apology—then a cat appears. Meanwhile at my end the postman calls and I have to answer. Each time the space resumes without fuss and each time I’m less fazed as the old orthodoxies crumble. And each time the soup of it feels richer, that’s the thing that quickens the pulse… that the relationship—the allotted time and space of it—can not only survive outside the physical confines of the room but actually increase in psychic compression by expanding to include the everyday.”

Coming from a school of therapy that founds its methods in phenomenology—the assumption that human embodiment is a given of the human condition, rather than something we have to reason our way into from the Cartesian position of a virtualised understanding—Nick’s enthusiasm may seem bizarre. But we must defer—at least a little—to someone who is actually doing this particular work, and at a time when rates of mental illness are increasing. Perhaps Nick’s hopes of zooming towards better psychological wellbeing represent the ultimate compensatory dyad of virtualising technology; the frisson that surrounds the intellectual apprehension of the other’s life-world substitutes for their physical presence—and provides far greater true empathy, as opposed to the messy and unpredictable sentiments afforded us by proximity and physical sympathy.

I hope so. Because if lockdowns, quarantines and social distancing measures stretch ahead of us into the future—while Facebook and Google tighten their techno-hold on the world’s governance à cause de la crise, we’re going to be in severe need of effective therapy to counter the mass waves of hysteria and neurosis that will, I predict, inevitably attend the full inception of the Machine, and the dawning of the age of Intensive Care.