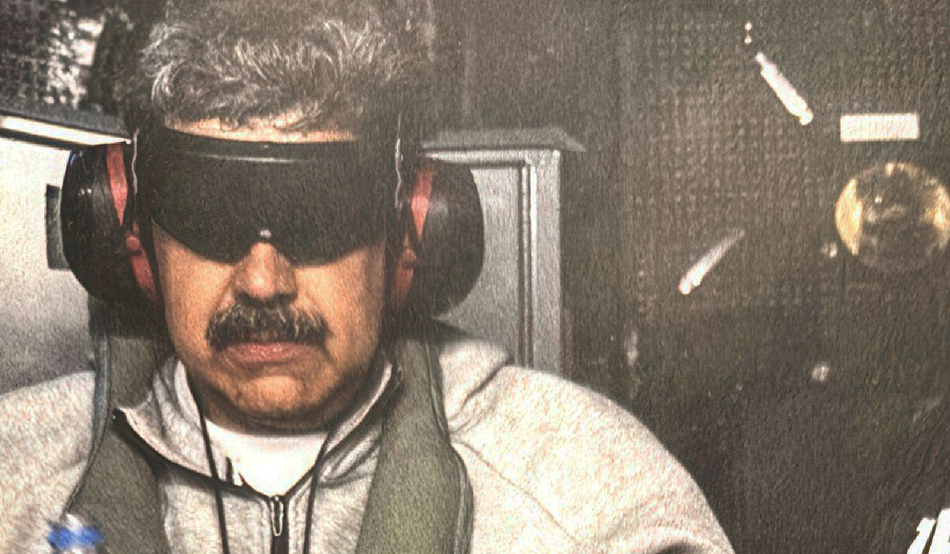

The capture and abduction of Nicolás Maduro was intended as a demonstration of strength. And in a narrow sense, it succeeded, confirming what few seriously doubt: that America’s military reach remains unmatched. If Washington decides to decapitate a regime, it often can.

But power has more than one register. And the deeper significance of Venezuela lies not in what the United States proved it can do, but in what it revealed it no longer wishes to be.

For most of the postwar period, American power rested on an unstable but extraordinarily effective combination: overwhelming military and economic capacity paired with a powerful moral and cultural appeal. The US did not merely coerce; it attracted. It offered itself—sometimes sincerely, sometimes hypocritically—as the embodiment of ideas others wanted to claim as their own: constitutional government, individual rights, social mobility, scientific modernity and a popular culture infused with optimism, irreverence and dissent. “American” once meant not just dominant, but better—at least in the imagination of many of those watching from afar.

This was no mere ideological window-dressing. Soft power was a real form of strength, built out of laboratories, courtrooms, classrooms, protest marches, movie studios and immigration lines—out of the visible capacity of a free society to innovate, to include, and to improve itself. From the space programme to Silicon Valley, US innovation signalled not conquest but possibility. Crucially, these advances circulated globally, inviting participation rather than obedience, and giving American influence a cooperative rather than coercive character.

American culture reinforced this appeal precisely because it was not monolithic or reverential. Hollywood, popular music and television exported not just glamour, but irony and self-critique. Jazz, rock and then hip-hop—forms born from marginalisation—became global languages. American culture looked unruly, plural and unfinished, and that messiness made it attractive. It lent credibility to political ideals that might otherwise have felt hollow.

This soft power lowered the cost of leadership. It helped turn allies into genuine partners. It allowed US influence to register, for many, as aspiration rather than submission. Even when American actions betrayed American ideals—and they often did—the ideals themselves retained independent force.

All of this helped stabilise the post–Second World War order America built, however imperfectly, in conscious opposition to the imperial logic that dominated the 19th century Atlantic world. That earlier model of power—territorial expansion, extraction, racial hierarchy and unapologetic subordination of those deemed inferior—had culminated in the devastation of two world wars. In response, the postwar order took shape around a different wager: that legitimacy mattered, that rules constrained even the strong, and that influence secured through consent and cooperation would ultimately prove more durable than control imposed by force.

Trump’s reinvention of the Monroe Doctrine represents a direct repudiation of that wager. On full display in Venezuela and in his threats towards Greenland, it has been stripped of its original defensive rationale and remade as a licence for extraction and domination. It marks a regression, but one with modern features: a fusion of 19th-century expansionism with 21st-century autocracy, in which law is treated as an obstacle, institutions as disposable and international cooperation as weakness.

What the Trump administration is doing in Venezuela and elsewhere is therefore not simply violating international law or abandoning the liberal, rules-based order it did so much to create and sustain. It is also dismantling the symbolic and moral infrastructure that made that order possible—squandering American soft power as it goes. Trump’s confused, ahistorical version of “greatness” rejects persuasion in favour of intimidation, legitimacy in favour of spectacle and leadership in favour of force. In doing so, it threatens to render American power indistinguishable from the lawless, illiberal rule exercised by regimes like Maduro’s—or Vladimir Putin’s.

Lacking the soft power Trump misunderstands and despises, authoritarian regimes have always fallen back on violence, territorial aggression and theatrical displays of strength. They rule populations they cannot inspire and face a world they cannot credibly lead. When authority cannot be grounded in legitimacy or shared ideals, it often resorts to threatening, brutalising and performing power endlessly instead.

This is the central irony of Trumpism. Obsessed with the decline of American power, it accelerates this decline. Venezuela magnifies the irony. In seeking to display American greatness by bringing Maduro to heel, Trump becomes a mirror image of the dictator. Abandoning the difficult work of lawful multilateralism, the president reaches instead for lawless force. This kind of power may be easy to wield, but it is far harder to sustain. Soft power does not return on command, and it cannot be restored through threats, wars, or monuments.

As an American living abroad, I see how the mythology that once surrounded my country—often exaggerated, sometimes deserved—has dramatically thinned. Under Trump, and especially after Venezuela, America can no longer plausibly present itself as the flawed steward of a grand shared project. It has instead recast itself as one more great power grabbing what it can and threatening to coerce those who stand in the way. The Venezuela operation will be remembered as a symptom of this voluntary self-abasement. In abandoning the ideals and agreements that once magnified its strength, the United States is not making itself great again. It is making itself smaller, more dangerous and less worth following.