“Johannes Vermeer is the most laconic of the Dutch old masters,” Andrew Graham-Dixon once remarked, adding that this “may explain why he has been the cause of so much volubility in others”. A quarter of a century on, Graham-Dixon is back with a whopping great study of the painter that, if never quite voluble, is far from laconic. Vermeer: A Life Lost and Found is many things—a critical biography, a history of the Golden Age of the Dutch Republic, a primer in iconography, an introduction to the techniques of art restoration, a guide to the methods of art authentication. Above all, though, the book is a tubthumping argument.

Graham-Dixon, who in his dedication tells us that he is the son of a barrister, has a case to make. That case is simply put. Vermeer wasn’t just the painter of some of the most creamily lyrical pictures in the history of art. He was a political and philosophical visionary, “a painter not of things but of ideas,” as ahead of his time as Voltaire and John Locke. “Once Vermeer’s place in history is properly understood,” says Graham-Dixon, “it becomes clear that he was one of a chosen few who built the values on which a tolerant and liberal civilisation, our own even, might be based.” Those are big claims to make of an artist on whom the dossier is so slender.

The few facts are these. Vermeer was born a Protestant in Delft in the United Provinces in 1632. In 1653, he likely converted to Catholicism when he married one Catharina Bolnes. Catharina bore him 15 children, 11 of whom survived. As well as being a painter, Vermeer was something of a dealer, and well enough respected by his peers to become one of the head honchos at the artists’ Guild of Saint Luke. Nonetheless, when he died in 1675 he was deep in debt—so deep that Catharina was declared insolvent.

Beyond this we know nothing. Nor is this a surprise. Back in Vermeer’s day, few law-abiding people left behind much—if any—trace of their existence. No letter by Vermeer survives, nothing of his ideas and theories about painting and painters, much less any record of his day-to-day life and conversation. Little wonder, says Graham-Dixon, that the French art critic and connoisseur Théophile Thoré, who did so much to revive Vermeer’s reputation in the mid-19th century, called him “The Sphinx of Delft”.

It doesn’t help that there are so few Vermeers to look at. We have no drawings by him, nor any preparatory sketches. (Vermeer was, Graham-Dixon reminds us, “one of the first [painters] to describe forms purely through gradations of light and shade, without recourse to line”.) The official record attributes just 35 pictures to Vermeer’s hand.

Make that 36, says Graham-Dixon, who is in no doubt that the Saint Praxedis (1655; all dates given are taken from the book and don’t always tally with the records elsewhere) in Tokyo’s National Museum of Western Art “was painted by Vermeer”. From beneath his horsehair peruke, he says we should ignore the doubters who have claimed that the picture’s signature and inscription were added long after it was finished. Instead, pay heed to the two sets of boffins who, working independently, have analysed the lead isotope ratio of the white pigment used in the painting and established beyond doubt that it is from the same batch which Vermeer used to paint Diana and Her Companions (1653).

This is art history of the old school, with facts and dates to the fore

This is impressive detective work, and Vermeer: A Life Lost and Found is studded with similar moments. Recent graduates in art history might be shocked at the way Graham-Dixon foregoes discussions of, say, Vermeer’s attitudes towards gender and domesticity or property and patriarchy, and doubly shocked at his Holmesian obsession with just who painted what, when, using what implements and chemicals. This is art history of the old school, with facts to the fore and dates bringing up the rear.

The military metaphor is apt because Graham-Dixon kicks things off with a long disquisition on what he calls Vermeer’s “Inheritance”—a history of the 70 or so years that preceded his birth—which is almost entirely about war. Fair enough. When Vermeer was born, the Eighty Years’ War (brutally summarised: northern Protestants seeking autonomy from heavily taxing Spanish Catholics) still had the best part of two decades to run. Nor is there any denying that Graham-Dixon has done his homework. If you want to know about the siege of Leiden or the Sack of Antwerp, or how “the massacres at Zutphen and Naarden changed the course of the Dutch Revolt”, he has all the relevant information.

But is all the information relevant? It is one thing for a biographer to sketch in a historical background. Our lives are, after all, ineluctably bound up with our times, and we can none of us be understood separate from them. It is quite another for him to fill in said background with so much photorealist detail that his subject becomes a blurry pointillist dot. We can none of us, after all, be explained solely by reference to our times. It’s not that history isn’t central to life. It’s that so much of life is tangential to history.

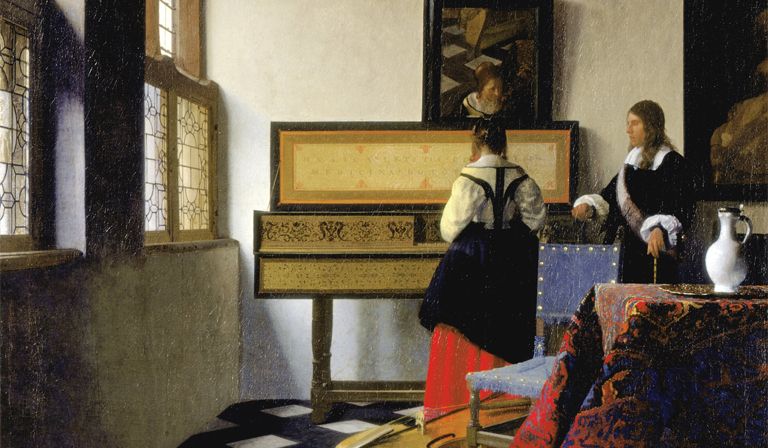

“What,” Graham-Dixon wonders after a dozen or so pages on Arminian resistance to Calvinist orthodoxy, “does all this have to do with Johannes Vermeer?” What indeed? To be sure, whatever Vermeer might have thought he was up to at his easel, the socioreligious strains and stresses of the age cannot but have been having their effect on him. But those strains and stresses were having their effect on everyone else too. Yet there was only one guy who painted The Little Street (1660) or The Music Lesson (1661-62).

Praise be, then, that for all the historical heavy-handedness, Graham-Dixon still contrives to give us the deepest and most rounded portrait of Vermeer we are ever likely to have. The portrait isn’t all that deep or rounded—given what Graham-Dixon calls “the archival void”, how could it be?—but if this Vermeer isn’t a wholly apprehended human being, then he is at least a wholly apprehended human type. We are dealing, Graham-Dixon argues, with an artist who believed his work could make the world a better place, a didactic painter whose almost blithely perfect pictures of seemingly quotidian scenes—a housefront in a quiet street, a woman in profile and gazing out of a window—are in fact gravid with significance.

Graham-Dixon made his name as an art critic on the Independent in its early glory days, and all his gifts of description and evocation are on display in his analyses of Vermeer’s work. I could fill this page with quotations that help you see the paintings more closely and clearly. Of The Guitar Player (1670), Graham-Dixon spots how “Her coiffure is a playful arrangement of tumbling ringlets that hang in the air against the back wall of the room like some new form of musical notation”. Of the Young Woman Standing at a Virginal (1670), he notes that she “is like a caryatid… perfectly upright, the folds in her white silk gown giving her the appearance of a fluted marble column”. No words can ever substitute for seeing a picture in the flesh, but if you can’t be there, then Graham-Dixon is the best parser of painterly effects since the late Robert Hughes.

The problems start when he passes from description to interpretation. “Vermeer’s work is many things,” he rightly argues, but is Woman with a Pearl Necklace (1665-67) really “a vindication of the rights of women”? Even if we allow Graham-Dixon’s assumption that the model for Girl with a Pearl Earring (1667-68) was Magdalena van Ruijven (the daughter of the couple for whom Vermeer was working), does it follow that the painting is really a portrait of Mary Magdalene? And even if it does, does this Magdalena really “turn with such depth of feeling” because she is reenacting for her family the scene from John’s Gospel in which Mary Magdalene realises that the gardener she has just been chatting to is the risen Christ? Because if it does, what is the no less coquettishly slack-jawed Taylor Swift turning to on the sleeve of her album Speak Now? Or Britney Spears on In the Zone?

The hermeneutics hit peak absurdity with what might well be Vermeer’s most famous picture, his View of Delft (1665). To you and me—and to Marcel Proust, who thought it “the most beautiful painting in the world”—this is simply (though there is, of course, nothing simple about it) one of the most piercingly precise studies of a townscape there’s ever going to be. But no, says Graham-Dixon. There’s far more to this picture than Vermeer’s granular registration of light and dark, sky and cloud, brick and water, beach and boat.

Calling on the Book of Revelation, with its references to the Lost Tribes of Israel and its prediction of the End of Days, and roping in “the lapsed Jewish philosopher Spinoza, who may have been in Vermeer’s circle” (that “may” does an awful lot of work there, as do the book’s countless variants thereon—“more than possible”, “seems probable”, “seems likely”, this can’t “be presented as truth, only possibility”—none of which would stand up in court), Graham-Dixon tells us that the View of Delft is “not a representation of reality” but a “prophetic vision” of heaven on earth. This is because “the sunlight flooding the scene is at its brightest, by implication, in the concealed centre of town”, where a couple of churches with which Vermeer had connections stand. It follows, apparently, that in “the world the picture dreams of there will be no distinction between one church and another, no more sects, no more division”. Hmm...

In a way, of course, the View of Delft is a vision of paradise. All great paintings are. Whatever their content, they usher us into a perfect space, an ideated arena of the ideal. Turner’s seascapes; Constable’s scenes of country life; Claude’s sunrises and sunsets; Monet’s waterlilies—like Vermeer’s eerily shimmering compositions, they grant us a vision of a world beyond the here and now.

Looking for meaning in these pictures is like looking for significance in the fact of your being alive

What’s oddest about Graham-Dixon’s readings is that he feels the need to make them. Pretty much ever since Vermeer’s rediscovery, it has been a critical commonplace that he is essentially a formalist—a painter not of subjects but of shapes and shades. This is not to say that he was some kind of prototype Clement Greenberg protégé bent on foregrounding the objecthood of the flat canvas. But it is to say that his paintings are so pointedly plain—a brick wall, a tiled floor, light filtering through a window on to a girl with a lute—that there is no meaningful way to talk about them beyond their efforts to, as that other (ancestrally Dutch) realist John Updike put it, “give the mundane its beautiful due”. Looking for meaning in these pictures is like looking for significance in the fact of your being alive. And anyway, art’s job isn’t to foist concealed lectures on us. It is to fix tiny moments of life in order that they might go on living.

But even if Graham-Dixon’s interpretations were susceptible of proof, the new meanings he finds in Vermeer’s work are so trifling they end up making the pictures seem shallower than we had hitherto thought. I suppose it’s possible that The Lacemaker (1671) is an allegory of pregnancy—something to do with that sewing cushion and its “torrent” of crimson thread. But if pregnancy were Vermeer’s real subject, why didn’t he just paint a picture of a woman with child? And if the meanings of these paintings really have been hidden for so long, how come so many people have been moved by them down the years?

I am being hard on this book because parts of it are so impressive. The depth of research, the passion for painting, the rhetorical power of Graham-Dixon’s properly critical appreciation, not to mention the glorious four-colour reproductions of Vermeer’s and his contemporaries’ work—they are almost enough to make up for the hectoring exegesis and laboured historicism. Almost. In the end though, Vermeer: A Life Lost and Found is no truer to its subject than Tracy Chevalier’s high-end period-piece potboiler Girl with a Pearl Earring. Case dismissed.