America's racial make-up is changing. You already knew that—but did you know how quickly?

Here, Shaun Bowler writes that the proportion of the population that is white is plummeting. Arguably, the effects are already being felt. A reason often cited for the remarkable rise of Donald Trump is that his supporters feel America is no longer built to benefit them. (In an excellent piece from our latest issue, Diane Roberts discusses Americans who long for a world where minorities "have rights—but not power.")

But here, Bowler takes a longer-term view. He analyses the data and presents demographic puzzles that, over the next few decades, the Republicans and Democrats will have to deal with—or they will face extinction.

This extract is taken from More Sex, Lies and the Ballot Box, edited by Philip Cowley and Robert Ford (Biteback, £14.99). Read our review of it here.

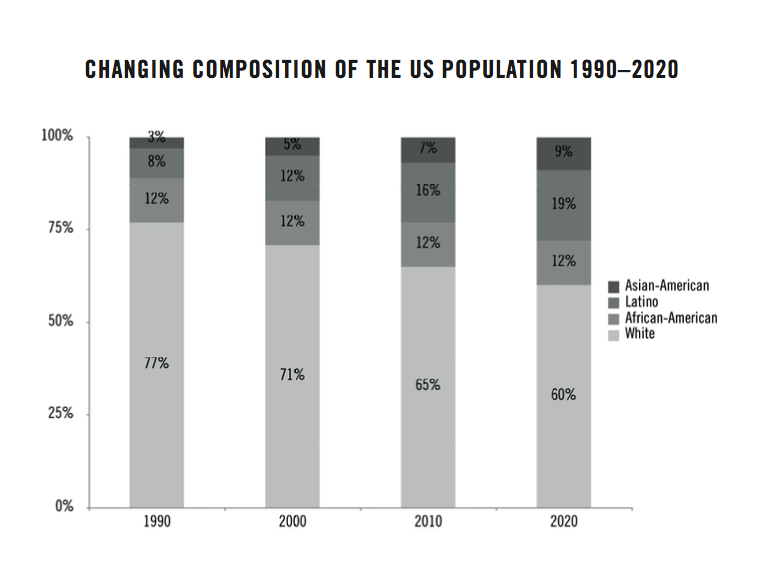

The US is changing fast. The share of the population and of the electorate who are white is dropping while the share of other racial and ethnic groups is growing. As the graph at the bottom of this post shows, the proportion who are white fell from 76 per cent in 1990 to 65 per cent in 2010; it is predicted to be just 60 per cent by 2020. On current trends, by 2044 the US will no longer be majority white.

These demographic changes present a series of challenges to some of the ways in which we think about political behaviour, which are typically based on research which focuses on the white majority. For example, the conventional understanding of political participation is that social attributes, especially education and income, are drivers of participation: the better off and the better educated take part more because they have the resources—financial and/or cognitive—to be able to do so. This tends to be much less true for Asian Americans, who, on average, have levels of income and education that should be associated with high political participation, but, as a group, currently participate much less than we would expect from our models. At the same time, African Americans participate more than we would expect from income and education levels.

One possibility is that differences in participation relate—at least somewhat—to immigrant status. Many Asian Americans are first-generation immigrants, and immigrants are often uncertain how to participate in their new home. Many may be fleeing regimes in which political participation was not seen as a good thing, or may prefer to avoid drawing potentially hostile attention to themselves. Yet this lower-than-expected participation persists even for many second (or more)-generation Asian Americans.

One influential line of argument emphasises how people are socialised into political attitudes from a very early age. Many people who immigrate did not grow up in their new home country, and so missed out on this socialisation process. How immigrants acquire attitudes and what attitudes they acquire are therefore interesting questions whose answers provide insight into, and amend our understanding of, processes of socialisation. The first generation of immigrants seems to have much more positive views of democracy and the US system of government than do those who have been brought up in the US. First-generation Latinos, for example, come to the US seeing the political system in very positive and supportive terms, often more positive than US-born whites. Successive generations, however, develop much gloomier views. This is identical to the process seen with non-white immigrants into the UK.

A third puzzle presented by changing US demographics is over the nature of identity politics. Social identities are powerful ways in which people see themselves and are seen in relation to society. In the US case, an especially important argument has been that of linked or shared fate. This argument, developed in relation to African-American experience but applied in recent scholarship to both Latinos and Asian Americans, holds that people have a set of shared histories and experiences, which lead them to consider themselves as part of a wider group and not just as individuals: injuries to individuals from a group are seen as injuries to the wider community as well. Where racial and ethnic identities overlap and are homogenous, then identities, and identity politics, may be clear-cut. In some ways that kind of identity politics makes it possible to talk of vote blocs such as "the African-American vote." Over the past generation, rising intermarriage between different racial and ethnic groups means that roughly 3 per cent of the US population now see themselves as "multi-racial"—and that group is growing fast. This group of people prompts some rethinking about identity politics.

These demographic changes also obviously matter to politicians because, as the electorate changes, so too do the electoral calculations they need to make. This is clearest in relation to the rapid rise in the Latino and Asian-American populations of the US, predicted to be almost 30 per cent of the overall population by 2020. Roughly speaking, Latino populations are largest in the southwest and west, Asian populations biggest in the west. Latinos comprise over 30 per cent of the population in four states: Arizona, California, New Mexico and Texas. For those familiar with the game of constructing electoral coalitions using the building blocks of social groups, this means that for many states a new vote bloc has to be considered and won over, or a bigger bloc needs more attention than previously. In many ways, the interests of these blocs of voters—schools, jobs, housing—are the same as any other bloc. But there are differences and distinctions. For example, immigration policy is an especially important concern to Latino voters. At the same time, while affirmative action policies resonate as a remedy for discrimination for African-American voters, Asian-American voters are often less supportive of such policies, especially with regard to areas such as university admissions. Candidates and campaigns, then, have to be careful how to address these issues and be more sensitive to issues of race and ethnicity as the electorate grows ever more diverse.

Historically, much of American politics has been "about" race and this isn’t going to change soon. Candidates have to be more mindful about the policies they stand for and the words and images they use in their campaigns. As a simple example, English-language ads in English-language news sources are no longer the only means of carrying a campaign message. While the fundamentals of electoral politics—organising, campaigning, voting—remain the same, the content of US politics will change in the coming century. It will be a century of new voices being heard.