The town of Ilulissat, with its brightly coloured wooden houses, sits on the banks of a spectacular ice fjord at the mouth of the Jakobshavn Glacier on the west coast of Greenland. With a population of around 5,000, it is the island’s third largest town, and the glacier that calves dramatically into its ice fjord is the likely origin of the iceberg that sank the Titanic.

Just 20 years ago, Ilulissat could boast a larger population of dogs—around 7,000—than humans. The dogs are the uniquely tough, sled-pulling Greenlandic huskies that have been the subject of recent sneers by Donald Trump. Like the humans who rear them, they live and work in one of the world’s most unforgiving environments, thriving in the long winter darkness that for so long spelled freedom, the time of year when the frozen sea ice opened up long routes to distant hunting grounds, some travelling as far as Kiatak, Herbert Island, Etah and the Humboldt Glacier.

Today, because of the climate change that Trump routinely denounces as a “hoax”, those journeys have become too dangerous: since 1980, the ice has been growing thinner and less stable, the risk of death on the ice greater. The winter horizons have shrunk, while the dog population has halved.

Greenlanders are adapting. Minik Rosing was born in Greenland and is now professor of geology at Copenhagen University. “The ice journeys are more dangerous,” he explains. “It transforms the winter and cultural identity is being lost, but for now there are some compensations. Open water fishing has now moved north to Thule and though free-ranging [roaming far across the ice] is no longer possible, people can see friends and family in other ways.”

The changes in the climate that are upending traditional Greenlandic culture have also transformed the wider Arctic—once one of the world’s more peaceful regions—into an unstable theatre of geopolitical, economic and strategic competition. It is into this already disturbed landscape that Trump has tossed his own hand grenade: his insistence, without evidence, that the United States “needs” to acquire Greenland for reasons of national security, and his threat—which he appeared to retract at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January—that it will do so by force if necessary. This is already destabilising Nato and undermining the US’s essential partnerships, with the United Kingdom and with the Nordic and the Baltic states, which underpin Arctic security.

The suggestion that the US could buy Greenland, now part of the sovereign kingdom of Denmark, has surfaced intermittently in Washington since the US bought Alaska from the Russian Empire in 1867. After all, the argument goes, 40 per cent of the US was acquired through purchase, most recently the former Danish West Indies (now the Virgin Islands), which Denmark sold to the US in 1916. But while previous transactions were conducted with willing sellers, Trump’s proposal more closely resembles a Mafia boss’s invitation to dinner. This is the offer you cannot refuse. The fact that you cannot refuse shows that it’s not an offer.

Washington’s Nato partners are appalled. Denmark, Greenland’s former colonial ruler, has firmly and repeatedly declined to sell. Greenlanders, whose collective ambition is for eventual independence from Denmark, are overwhelmingly opposed. Indeed, given that Greenland is a semi-autonomous territory, with its own parliament under the Act on Greenland Self-Government of June 2009, it is doubtful that Denmark could legally sell Greenland, or that Greenland, until it is fully independent, could legally sell itself. There is, in any event, no inclination to do so. As the chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Council and a member of Greenland’s parliament, Sara Olsvig, put it in a recent webinar: “It has been very, very clear that the sentiment here is that we have already been colonised once. We do not need to be colonised once again.”

Rosing agrees: “People are extremely fed up with the rhetoric, the lack of seriousness and the lack of understanding of Greenland. People in Greenland take this very seriously and don’t find it a laughing matter to hear Americans joke about taking their home. People feel wealthy already and don’t want to change their way of life for easy money. They feel they live good lives; they have health and dental care. It is not somewhere you can arrive and drop glass beads and see everyone roll over.”

But if Trump’s acquisition plan has aroused anxiety and hostility in Greenland, his concern for national security in a changing Arctic has some foundation. Trump may claim that climate change is a myth, but it has created opportunities for Russia, the biggest Arctic power, and for Moscow’s close collaborator and self-declared “near Arctic state”, China. Together they seek to dominate the resources and logistical opportunities that a transformed Arctic could offer.

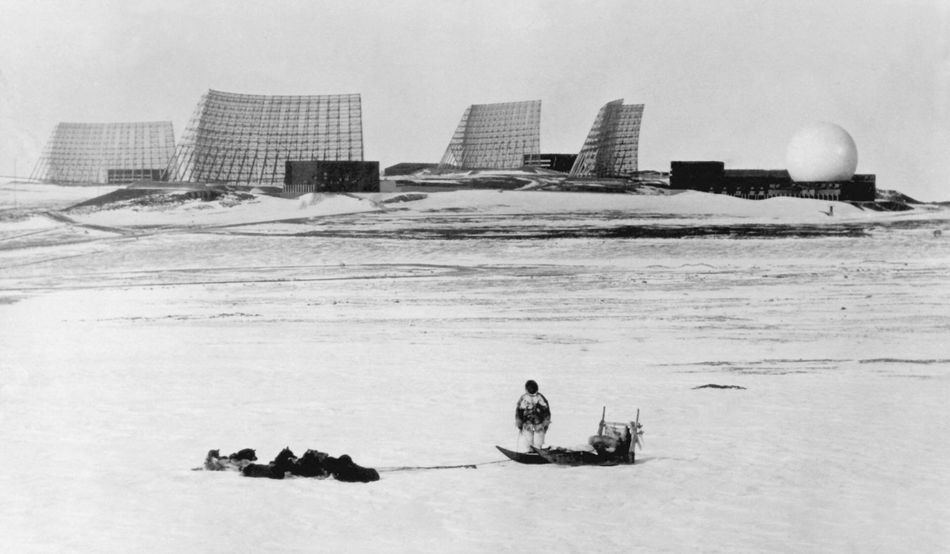

The region has long been a site of strategic rivalry. The US has been a security partner of Greenland since the Second World War, when American bases in western and southern Greenland became crucial refuelling stops for planes flying to Europe, and American soldiers garrisoned at Ivittuut, on the south Greenland coast, protected the world’s largest cryolite mine, essential for smelting aluminium. Both the Americans and the Germans built weather stations to provide forecasts for military operations in Europe. During the Cold War, the US maintained 10,000 troops and several bases in Greenland under a 1951 agreement that remains in place. By the time the Cold War ended, US attention was elsewhere, its presence much reduced. Today it has barely 100 military personnel on the island.

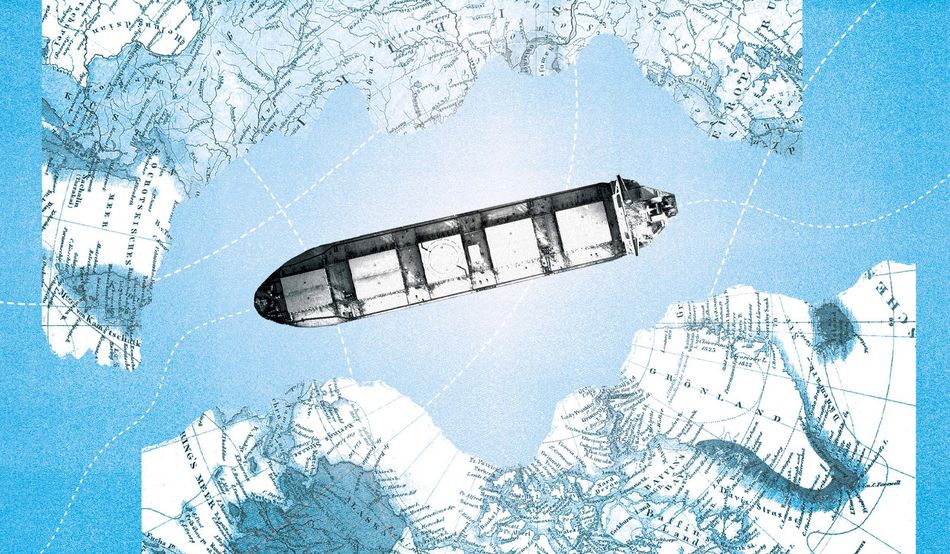

While China has no military bases in the Arctic, Moscow maintains 12, along with 16 deepwater ports and a nuclear-powered icebreaker fleet. These give it year-round capacity to dominate its Arctic waters, including the newly navigable Northern Sea Route—a shipping passage free of the danger zones and potential choke points of transit through the Suez Canal and the Malacca Strait. Beijing currently operates three icebreakers, two more than the US, and is reportedly working with Russia to develop a year-round container ship capable of transiting the Arctic. While the US steadily reduced its military and security effort in Greenland after the end of the Cold War, Russia and China have grown steadily closer since their 2022 announcement of “limitless friendship” and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

But China’s interest in the Arctic has deeper roots, and has become a key element in Xi Jinping’s global effort to build Chinese influence. China acquired its first icebreaker in 1993 from Ukraine, as the melting Arctic ice began to open the prospect of passage through the shorter, Russian-controlled Northern Sea Route.

When the Russian minister of emergency situations, Sergei Shoigu, suggested in 2011 that Russia and China collaborate to build a “Silk Road on ice” as a joint investment along the Northern Sea Route, the idea was still a little ahead of its time. Then, in 2013, China successfully applied (along with five other non-Arctic states) for an observer seat on the Arctic Council. In 2017, China formally introduced the Polar Silk Road as an element of the Belt and Road Initiative, Xi’s ambitious international infrastructure programme.

A year later, China clarified its Arctic ambitions in its first “Arctic Policy” white paper. Here, China made two arguments. First, that a country of both its size and proximity had the right to be treated as an important Arctic stakeholder. Second, that since climate change will bring transformations of global importance, non-Arctic states also have the right to access resources and participate in the shaping of the new rules of navigation, research, overflight and economic exploitation. Unlike Trump, China also promised to defend the territorial integrity and national sovereignty of the Arctic nations.

It was clear from the paper that the Arctic figured prominently in Xi’s grand strategy to make China a great power: it had become a new frontier. Not only did the Northern Sea Route offer the potential of a quicker and cheaper shipping route between China and Europe, it would also require investment in new ports, transport and communications infrastructure—exactly the kind of opportunities China sought and continues to seek.

As a non-Arctic power, China needs Russia to maintain a secure Arctic foothold. Russia, in turn, needs Chinese investment and the Chinese market to sustain its exploitation of Arctic oil and gas. In an early commitment back in 2013, China invested alongside France in a liquid natural gas project (LNG) on Russia’s Yamal peninsula. It was China’s largest investment project in Russia and the largest LNG project in the world. Yamal LNG is exported to Europe, despite the sanctions imposed on Moscow following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine and, in the summer, to northeast Asia. The first LNG shipment was delivered to China by the Northern Sea Route in July 2018.

Beyond its partnership with Russia, China’s vision for the Polar Silk Road included investments across the Arctic and active pan-Arctic diplomacy. It negotiated with Iceland over a 10,500km data cable project, with Finland and Norway over a new railway line and with Sweden over investment to expand the port of Lysekil, north of Gothenburg. China has also set up scientific research projects in Iceland and Svalbard, Norway. In Greenland, it set its sights on establishing a research station and satellite receiver station, buying a disused naval base and financing the construction of three airports.

As Chinese ambitions grew, so did concerns about longterm security risks

At first, these initiatives were welcomed by many in a region that has struggled to attract interest and investment. China was proactive, keen and, for the time being, relatively flush with cash. But the politics, not least between Copenhagen and the Greenlandic capital of Nuuk, were sensitive; the presence of a new player in that ever-volatile relationship could trigger unpredictable reactions.

For Greenland, China offered potential investment and the opportunity to play a larger role in the new dynamics of the region. Aleqa Hammond, the territory’s one-time controversial and outspoken prime minister, said Greenland had “no trouble” including Chinese companies in the development of Greenland’s infrastructure.

Denmark, too, once welcomed Chinese interest: in 2008 it became one of the few European countries to sign a “comprehensive strategic partnership” with Beijing. But, as Chinese ambitions grew, so too did concerns in Copenhagen both about the longterm security risks of a Chinese presence, and the possibility that such investment could further excite Greenland’s ambitions for independence.

In 2017, the annual report of the Danish Defence Intelligence Service warned of the risks posed by Chinese investment in Greenland, while the Danish Ministry of Defence pointed out the close relationship in the Chinese system between commercial and strategic interests. Those concerns also had some foundation: despite careful diplomatic balancing of attention between Nuuk and Copenhagen, several Chinese scholars and analysts published papers suggesting that an independent Greenland could serve as China’s permanent Arctic base.

In December 2016, the Danish government’s concerns became public when it abruptly withdrew from sale the disused Grønnedal naval station in southern Greenland. Subsequent media leaks suggested that the change of heart was triggered by a bid from General Nice, a mining company based in Hong Kong.

The following year brought a diplomatic standoff. The Greenlandic government had repeatedly sought financial support from Denmark for the development of three airports—one in Nuuk, one in Ilulissat and a third in the south of the island. Since the Danish government had declined to help, Greenland’s then prime minister Kim Kielsen flew to Beijing for discussions with the more receptive China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China. Loans could be forthcoming, he discovered, especially if Chinese companies were involved in the construction of the $555m projects.

Among the bids that followed was one from the China Communications Construction Company, blacklisted by the World Bank over a fraudulently inflated bid for a road project in the Philippines and by the US for its part in building artificial islands in the South China Sea. When news of the bid reached Washington, US defence secretary Jim Mattis reportedly made it clear to his Danish counterpart, Claus Frederiksen, that the deal could not go ahead. Denmark would have to intervene.

The Danish prime minster at the time, Lars Løkke Rasmussen, abruptly reversed his position. Two of the airports would be financed by favourable Danish government loans and Nuuk itself would finance the third. The US Department of Defense also offered to chip in with some airport infrastructure. For those Greenlandic politicians who preferred Chinese influence to that of Denmark, this was not an entirely welcome outcome. Several left the governing coalition and Kielsen’s government collapsed.

As well as opening the Arctic to geopolitical competition, the melting ice has raised the possibility that Greenland’s rich mineral and energy resources could become more vulnerable to exploitation. The US Geological Survey has estimated that the Arctic contains 13 per cent of the world’s undiscovered conventional oil and 30 per cent of undiscovered conventional gas resources. Greenland is also home to substantial reserves of rare earth elements, including some of the largest known reserves of scandium, yttrium, dysprosium and neodymium. There are coastal deposits, but much of this promised bounty lies under the ice cap.

Successive Greenlandic governments have sought finance and interest from international companies, including those in the US, to develop their mining sector. While he was Greenland’s prime minister, Múte Bourup Egede visited Washington in June 2022 to try to drum up investment in sustainable mining. “Our closest friends,” he remarked, “have not invested as we wished in the last few years, so now we are coming to our friends and saying: if you want to invest in the Arctic, you can’t ignore Greenland.”

There was interest, however, from a Chinese company. In 2013 and 2014, China Nonferrous Metal Mining Group had entered a non-binding agreement to finance and construct a mine developed by Ironbark Zinc, an Australian company, in northern Greenland’s Citronen Fjord. Ironbark finally decided against Chinese finance, however, and sold its interests in the mine in December 2024.

Far from taking over Greenland’s resources, Beijing has been shut out. China currently has no mining interest in Greenland, but two US companies are already engaged with a rare earth project in southern Greenland. The Greenlandic government has been clear that it would welcome more interest from its “closest friends”.

Minik Rosing points out that the Greenland government has been inviting investment and attending the annual Toronto conference of the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada for 20 years to try to stimulate interest. “Nobody came,” Rosing says. “But the idea that [Americans] were prevented from coming is ridiculous. The problems are more to do with the business case—the small market and the lack of processing capacity, the lack of infrastructure in Greenland and the fact that there is no unemployment, so where would the labour come from?”

Greenlanders would welcome serious US interest to help them overcome the obstacles to mineral exploitation listed by Rosing. But Trump’s approach to their homeland has hardened sentiment: in March, voters rejected the more radical pro-independence party in favour of a moderate government, and today his threats of a hostile takeover have killed off any potential attraction of a closer association with Washington.

“People are really fed up,” says Rosing. “The lack of respect, the ignorance and the lack of seriousness in the way this is being conducted. Social media is not the place to talk about taking somebody’s home.”

The permafrost on which the island’s structures are built is thawing, destabilising critical sites

The White House justifies Trump’s position by repeating his insistence that possessing Greenland is necessary for US national security, despite the US having had uninterrupted security access to the island for more than 70 years; no evidence of an increased threat to the island has been forthcoming. His claim of the presence of Russian and Chinese ships is contradicted by his own security forces; while they note increased Chinese and Russian naval activity, it is not around Greenland but to the west of the sovereign US territory of Alaska.

Trump’s remarks about dogsleds notwithstanding, the US is not—unlike its Nordic allies—currently well equipped to defend Greenland, where the effects of climate change are undermining existing American installations. The melting ice sheet is producing floods that have swept away bridges and the permafrost on which the island’s structures are built is thawing, destabilising critical sites such as the radar installation and runway at Pituffik Space Base.

The US lacks the trained personnel, the equipment and even the icebreakers to mount a defence of Greenland, and its own strategic assessments call for closer cooperation with Nato over Arctic defence. As the US Arctic Strategy, published in 2024, points out: “Collaboration in this region among Unified Combatant Commands (CCMDs) and Arctic Allies is critical to collective defense of NATO Allies and to U.S. homeland defense. The accession of new NATO Allies and the strengthening of the Alliance opens strategic opportunities and supports critical objectives…”

It is that critical collaboration that Trump’s approach puts at risk.

Nevertheless, his government has reportedly given administrative oversight of Greenland to the National Security Council official responsible for the western hemisphere, not Europe, and in January threatened his closest allies with steep tariffs if they oppose his will.

It is difficult to see anything other than deeply damaging consequences for the US, should Trump continue to insist on seizing Greenland. So why has it become such an obsession?

Trump’s first reported mention of Greenland came on 15th August 2019, when the Wall Street Journal reported that he had expressed interest in buying it from Denmark. Three days later, Trump confirmed the report, telling reporters: “We’re looking at it. It’s not number one on the burner… strategically, it’s interesting.”

The following day, he posted a social media image of a Trump tower in Greenland. The Greenlandic government responded that “Greenland is open for business, not for sale,” while Danish prime minister Mette Frederiksen called the idea “absurd”. Trump duly cancelled a planned visit to Denmark. Back in Washington, puzzled aides began to research scenarios and legal possibilities, while trying to calm the diplomatic waves.

Two people in Trump’s circle profess to have given him the idea he now claims as his own. One is billionaire Ronald Lauder of the $29bn makeup brand Estée Lauder, a personal friend of the president who had been exploring investments on the island. The other is the Republican senator Tom Cotton.

A former military officer, Cotton chairs the Senate Intelligence Committee but had no prior record of interest in the Arctic. Once the news of Trump’s interest in Greenland broke, however, he told an Arkansas newspaper: “I talked to the President multiple times about it. I know he’s interested in the potential purchase of Greenland for strategic reasons.” On 26th August 2019, Cotton put his name to an editorial in the New York Times arguing in favour of the purchase and claiming to have discussed the proposal with the Danish ambassador to Washington.

As the diplomatic fallout continued through that autumn, Cotton’s name was associated with an even stranger episode: a letter from Ane Lone Bagger, Greenland’s minister of education, culture, church and foreign affairs, dated 23rd October 2019, began to circulate on social media.

Written in English and on the minster’s headed notepaper, it promised that the government was anxious to proceed towards independence as quickly as possible and keen to pursue closer integration with the US. The government, according to the letter, accepted the US proposal that Greenland have the status of an “organised non-aligned territory”, and asked Cotton for an extra 30 per cent over the agreed budget to fund the referendum on independence from Denmark.

Cotton’s office has never confirmed or denied receipt of this surprising letter. What is clear, however, is that it was a forgery. It was swiftly disowned by Bagger’s office and Danish intelligence subsequently concluded that Russia was responsible, its apparent objective being to further tensions between Nuuk, Copenhagen and Washington—something Russia, of course, has denied.

In Greenland and in the capitals of Europe, the reputation of the US is melting faster than Greenland’s ice sheet. Even if the US does now lower its threat level and promise of a wider Arctic deal, the loss of trust is unlikely to be fully remedied. The clearest beneficiary of Trump’s threatening behaviour in reputational terms is Beijing. A recent survey carried out by the European Council on Foreign Relations and Oxford University found that China is now seen in most countries as a more reliable actor than the US. In hard security terms, the likely beneficiary of Trump’s behaviour is Russia.

Putin’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine provoked the previously neutral Finland and Sweden to join Nato, leaving Moscow facing a full set of Arctic Nato powers with conventional forces far greater than Russia’s, and whom Russia could not hope to defeat. Until now, breaking up that alliance was something that Putin could only dream of. If Trump persists, the US president could deliver it for him on a golden platter.