While David Cameron was making his speech on immigration at the Home Office yesterday (he blamed the Liberal Democrats for blocking the coalition government's attempts to reduce the level of net migration to the UK), his former senior adviser Steve Hilton was in Prospect's offices in London for a roundtable discussion with a group of journalists and policy professionals about his new book, More Human: Designing a World Where People Come First.

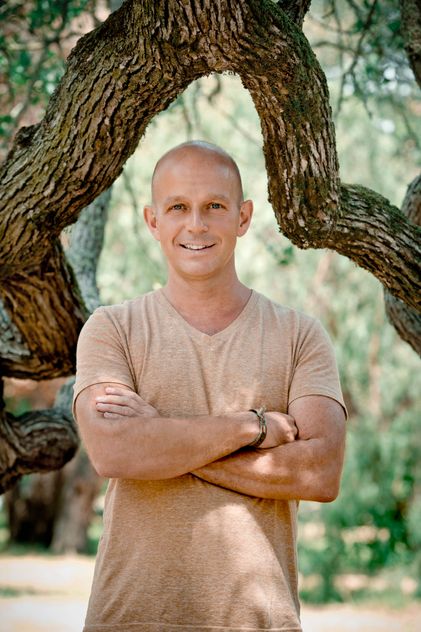

After he left Downing Street in May 2012, complaining about the obstacles that the Whitehall machine had put in the way of his attempts to transform how the government was run, Hilton moved with his family to California. He's still there—he's now CEO of a Silicon Valley start-up and a visiting professor at Stanford—and his book is saturated in the kind of optimism (or boosterism, depending on one's taste) often associated with the "Golden State." (Scott and Jason Bade, Hilton's two co-authors—who, he said, provided the "facts to buttress [his] prejudices"—are themselves both twenty-something scions of Silicon Valley.) Hilton pays tribute to the distinctive atmosphere of his new home in the introduction to More Human, particularly to the "entrepreneurial community at Stanford University" that has, he says, shaped his thinking about what he still calls (and the Prime Minister used to call) the "post-bureaucratic age."

More Human is a manifesto for the post-bureaucratic age, then; a blueprint for new kinds of institutions (and not just government ones, but in education and business, too) designed on a human scale. But, Hilton insisted yesterday, "this is not a 'small is beautiful' argument." He's less interested in the size of institutions, he said, than in dislodging "concentrations" of political and economic power wherever they occur.

Inevitably, much of the blanket media coverage of Hilton's book has concentrated on the extent to which his ideas have survived both contact with the upper echelons of the Civil Service while he was in government and then his departure in 2012. Does Hiltonism endure even though its originator no longer has an office in Number 10? One could be forgiven for being sceptical—and not just because the Tories have just run a successful election campaign that was decidedly un-Californian in tone. The knighthood to be conferred on Eric Pickles, the former Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, might, for instance, be interpreted as a reward for ensuring that the Hiltonite obsession with localism (in the book he advocates what he now calls, in Silicon Valley jargon, "MVG," or "Minimum Viable Government") didn't do too much damage. That said, Hilton could plausibly claim some responsibility, however remote, for George Osborne's agenda for the devolution of power to cities like Manchester—even if the Chancellor's rhetoric and demeanour couldn't be less evocative of the West Coast of the United States.

Prospect has taken a close interest in that agenda (as well as expressing qualified enthusiasm for it), particularly in our "Blueprint for Britain" series on the constitutional changes we believe the country needs. But we're also sensitive to the costs, as well as the benefits, of redistributing power from the centre. Some of these costs were set out forcefully at the roundtable yesterday by Matthew Parris of the Times. "Isn't the centralising of power," Parris asked, "a means by which the poor and less successful can be assisted? And doesn't the fragmentation of power very often redound to the advantage of the privileged and successful in society?"

In response, Hilton rehearsed the brief history of the rise of bureaucratic systems of government that he sketches in the book. "In the 2oth century, centralised bureaucratic systems delivered huge advances—no doubt about it. The NHS, state education and the welfare system lifted people up in a dramatic way. What I think is that they have reached the limit of their usefulness. In the terms of the poorest [in society]—if we want them to genuinely have a life worth living, that requires a really personal connection. The reasons that a family might be stuck, or an individual might be stuck… are very human and personal. Stuff has gone on in their lives that needs personal attention. All the answers to these problems in the end come back to individuals working with each other. Patient interaction with a person to get them back on track… can't be delivered by someone in Whitehall. It's decentralisation to that individual level that I'm talking about. The other thing that's really important is that accountability is devolved. You need political accountability at the local level."

Some round the table wondered whether Hilton was conflating the question of how public services are delivered—and of course tailored, targeted intervention in the often chaotic lives of the deprived is better than "cookie-cutter" solutions bought off the peg in Whitehall—with the question of who is responsible for delivering them. Did Hilton mean to say, Peter Riddell of the Institute for Government asked, that "central government just does the core things of defence and presumably pensions," leaving the rest to be handled at the local level (whether in the new "city-regions" or in county councils)? "And how do you draw up a funding model?"

Hilton didn't quite bite the bullet. "The principle should be that you devolve the funding, as well as the power. The US is a better model in that respect. Local taxes are standard. Tax competition between different areas is not something people think is outlandish or weird."

The book is full of American examples like this. But what works for California wouldn't necessarily work for Cornwall. Having "crazy ideas" (Hilton's own words) is one thing. What the despised bureaucrats call "delivery" is quite another.

Steve Hilton's "More Human: Designing a World Where People Come First" is published by WH Allen (£18.99)

The following people were present at Prospect's roundtable with Steve Hilton: Matthew d'Ancona, journalist and author; Jonathan Derbyshire, managing editor, Prospect; Bill Emmott, former editor of the Economist; Tony Grew, editor and founder of PARLY; Richard Harries, deputy director, Reform; Ben Judah, journalist and writer; Serena Kutchinsky, digital editor, Prospect; Josh Lowe, deputy digital editor, Prospect; Bronwen Maddox editor, Prospect; Emran Mian, director of the Social Market Foundation; John McTernan, former political secretary to Tony Blair; Matthew Parris, columnist, the Times; Jonathan Refoy, director of external affairs, CH2M Hill; Peter Riddell, director, Institute for Government; Alice Thomson, columnist, the Times.

Steve Hilton: California dreamin'

The prodigal son returns to some hard questions about the risks involved in giving away power

May 22, 2015