The headline of a spoof article in Private Eye in early July read: “Turkeys Vote for Christmas in Referendum Cliff-hanger." The meaning was obvious—the people who had voted to Leave the European Union were probably those were going to suffer the most from Brexit. But is that true? Our new analysis can provide a few pointers.

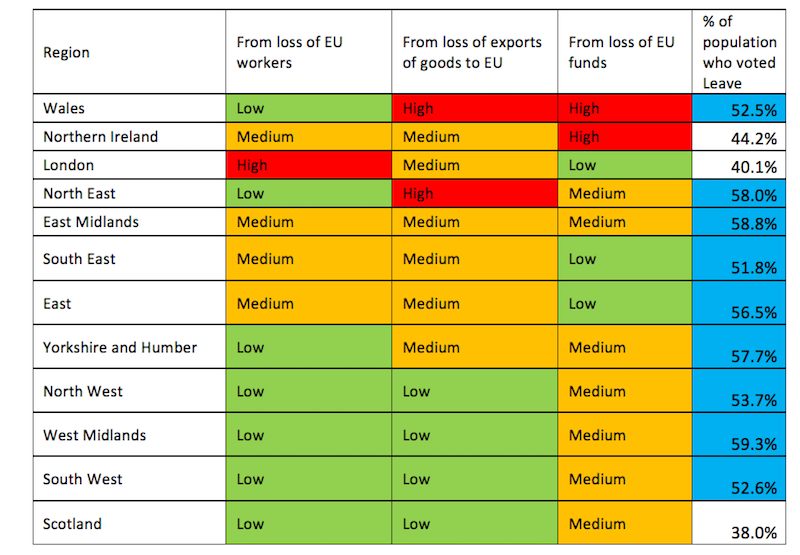

No one knows what the exact economic implications of Brexit will be. But the government has made it clear that we are leaving the Single Market and probably the customs union. Brexit will also mean exiting EU policies that support poorer areas. So, we looked at how the different regions varied in terms of their dependence on EU labour, the proportion of their exports that go to the EU and the amount of structural funds they receive. (These funds are allocated by the EU to poorer places to help increase productivity). The results are summarised below, along with the proportion of voters who voted Leave in the referendum.

The regions are listed roughly in the order of the magnitude of risk they face from three factors: loss of EU workers, loss of exports to the EU and loss of EU structural funds. So, for instance, Wales employs relatively few EU workers (just 3 per cent), but nearly two-thirds of its exports go to the EU (the highest of any region) and EU structural funds are the highest of any region (nearly 1 per cent of regional Gross Value Added). The last column is the proportion of the region that voted Leave, highlighted blue where that was the majority vote.

The idea that the areas which voted Leave stand to lose the most from Brexit has some validity—see the results for Wales and the North East. And yet it’s not as simple as that. Some areas that are at high risk from Brexit, such as Northern Ireland and London, voted to Remain. One might say the same about the West Midlands, which voted to Leave and faces a relatively low risk from Brexit. But then there is Scotland, which had the lowest Leave vote of any region but is also at relatively low risk from Brexit.

What this suggests, is something that we probably already knew—that the vote to Leave wasn’t based on a clear-headed analysis of the economic risks and rewards of leaving. But that is not to say that it was simply stupidity or an act of self-harm, as some commentators are prone to conclude. It probably just wasn’t about the economy. And that conclusion applies as much to Remain voters as it does to Leave ones—otherwise, Scottish voters might well have decided it was worth a punt.

Of course, we still don’t know what Brexit is an exit to. Only then will the regional ramifications become clearer. Even then, the implications are unpredictable: changes to trading arrangements or regulations will ripple through the economy in unforeseeable ways. But crudely, if we ask whether the turkeys voted for Christmas, the answer is: some, but probably not most of them. In any case, people care about much more than economics.