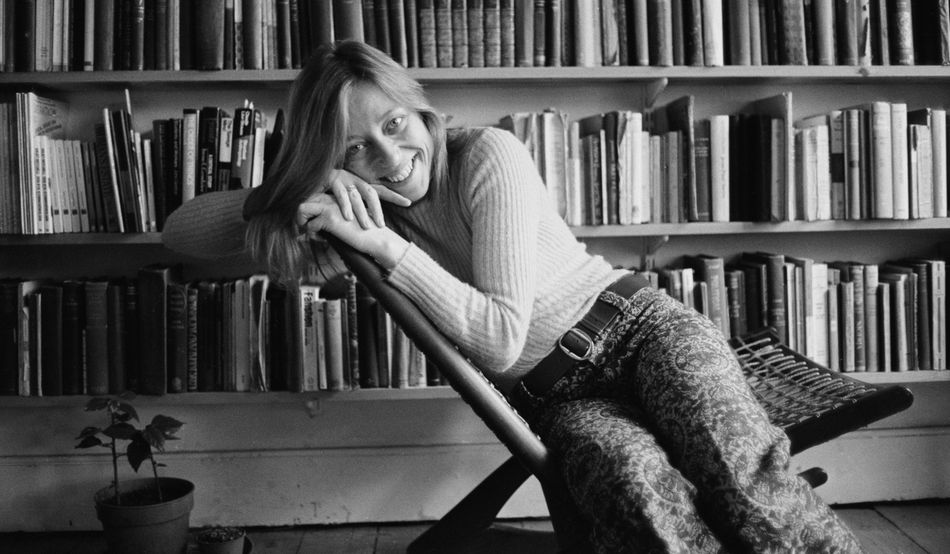

In 1966, an essay far ahead of its time appeared in the pages of the New Left Review (NLR). “Women: The Longest Revolution” was an analysis of how women are produced as a class. Its author, Juliet Mitchell, then a lecturer in English at Leeds University, was one of the people behind the new socialism that was emerging at the time in a reaction against Marxist orthodoxies. With the Women’s Liberation Movement still nascent in Britain, her New Left colleagues weren’t convinced that “women” was a topic worthy of an essay. Mitchell, who was married to Perry Anderson when he became editor of the NLR in 1962, has written about the editorial board meeting in which she, the only woman around the table, pitched her idea. “I was told emphatically that it was not a subject.”

Drawing on Louis Althusser’s structural Marxism, Mitchell would argue that the position of women was produced by a “complex unity” of “structures”—“Production, Reproduction, Sex and Socialization of children”. The concept of “complex unity” applied to women was cutting edge, and arguably prefigured what is now commonly known as intersectionality. As Mitchell wrote back then, “The four elements of women’s condition cannot merely be considered each in isolation. They form a structure of specific interrelation.” This wasn’t identitarian as such, but Mitchell saw that you couldn’t fully understand women’s oppression without noticing the knotty, interdependent layers that created and comprised it.

Despite the initial incredulity of her New Left peers, “Women: The Longest Revolution” soon found its audience in the burgeoning feminist movement. The essay “was widely translated and pirated with my happy connivance”, Mitchell has written. In 1971, it would become a book, Woman’s Estate, written in only six weeks “in the huge excitement about feminism” (the title was adapted from a William Blake poem). Last year, just over a half-century later, it was reissued by Verso with a new preface by Mitchell, now in her eighties.

This work was only the very start of a decades-long career. The coming years would take Mitchell from lecturing in English at Leeds University and being at the centre of the New Left, to becoming one of the most influential thinkers of second-wave feminism and psychoanalysis (she trained as a psychoanalyst in the 1970s—more on that later). And just as she started, Mitchell would continue to be pioneering: to see the things that others missed.

I met Mitchell twice in 2025: first, on a spring day at Jesus College, Cambridge, where the professor emeritus and founder director of the university’s Centre for Gender Studies has an office; second, in the autumn, at the house she used to share with her third husband, the social anthropologist John Rankine Goody, who died a decade ago.

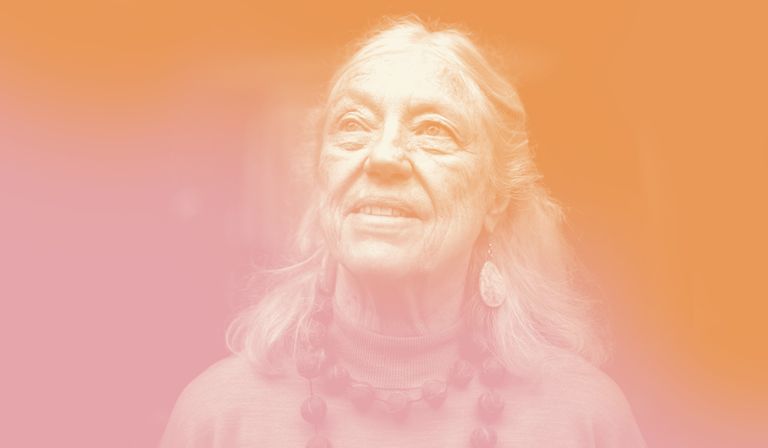

Back in April, the woman who approached me in a sunlit college quad wore long red flower-shaped earrings (her favourite jewellery, alongside rings; she could “take or leave” bracelets and brooches) and a navy sun hat. She had smiling blue eyes and shoulder-length white hair, and she moved with the help of two walking sticks.

“There’s something very nice about old age, which people don’t realise,” she told me later over coffee, reflecting on the physical indignities of being elderly, “which is that you could pop off any moment and you don’t need to bother, in a sense.”

Mitchell was born in 1940 in New Zealand, moving to England with her mother in 1944. She studied English at Oxford, then taught at Leeds and at Reading. Growing up in the 1950s, “the big change” on the left “was people leaving the Communist party. That was huge.” In the 1960s, she became active in socialist and feminist politics.

The 85-year-old still thinks of herself as a socialist and a feminist—and has by no means retired. The night before we met, her day ended at 9.45pm; she had met online with a psychology group she established when she joined the college in the late 1990s. At a long, dark wooden table in the faculty dining room, over celeriac chowder and salmon, Mitchell told me about her latest project: a book on Louise Bourgeois—her life in analysis and what made her so exceptional. The French-American artist—known globally for her nine-metre-high sculptures of spiders, among other works—spent years under intensive analysis and made 1,000 pages of notes on her therapy.

Mitchell thinks carefully before she speaks, and when she does it’s often quiet. Every once in a while, she laughs with self-deprecation. “There’s no question that she was exceptional. There’s no question she was extraordinary,” she says of her subject. “Bourgeois was brave enough to be mad and to live with her madness.”

The two were due to meet, though Bourgeois died, aged 98 in 2010, just before they could. Still, Mitchell’s memories are littered with fantasy dinner party participants of the highest calibre. With Ms Magazine founder Gloria Steinem she recalls (in the new preface to Woman’s Estate) “tap-dancing with excitement… in celebration of the founding of the National Organization of Women (NOW) in 1966”. She was also “very friendly” with Betty Friedan, author of The Feminine Mystique, the 1963 book considered one of the sparks for the second wave, the period of feminist activism that lasted until the 1980s and focused on women’s legal, social and economic rights. She still wears a coat she bought with Friedan when the pair sneaked out of a meeting to go shopping in New York. She refers to Judith Butler, a former visiting professor at the Cambridge Centre for Gender Studies, as Judy (the world-famous philosopher wrote a highly complimentary cover blurb for the new edition of Woman’s Estate).

In the early 1960s, Mitchell met Simone de Beauvoir, author of another foundational feminist text, The Second Sex (1949), along with the philosopher’s then lover, the film director Claude Lanzmann. She got to know de Beauvoir “quite well”. The pair marched together in Paris against the criminalisation of abortion, she recalls, with placards reading: “We’ve had abortions, please imprison us.”

What was de Beauvoir like? “Very open minded, very honest, very integrated, very courageous.” They argued “very strongly”—and often about psychoanalysis. But, de Beauvoir noted in her autobiography, Mitchell convinced her to think differently about Freud. “When all is said and done,” observes Mitchell now, “she says I changed her mind.”

Indeed, it was with her contrarian arguments on Freud that Mitchell would gain even greater notoriety as a feminist voice. The father of psychoanalysis was pilloried at the time. As Mitchell put it in a 2004 interview published in the journal October, he was seen as “the arch-patriarch”. “He was a bad face on the calendar, and they put the dart through his eye”, she tells me.

But Mitchell wanted to know more, so she read Freud. “Wait a minute,” she remembers thinking. “This is a different thing altogether.” His ideas were “terribly useful for understanding the position of women, not something that you want to reject”. Of course, Freud could and would be critiqued, but “rather than abuse him, we have to use him”. When Mitchell’s second book, Psychoanalysis and Feminism, was published in 1974 (it, too, has now been reissued by Verso, in January this year), there was “shock” in the United States and objection from her friends.

Even earlier, however, Mitchell noticed how feminism overlooked the ways in which oppression operates within us. Woman’s Estate had a chapter on psychoanalysis. The “role and nature” of the family needed to be understood “from within”, she wrote.

In that 2004 interview, Mitchell reflected on how she makes up for gaps in her own thinking. “I’ve begun to think that perhaps everything I do is because of something missing in what I’ve just done,” she said. “After ‘The Longest Revolution’, I felt I hadn’t considered how sexual difference was internalised so that, even when we didn’t think about it, it is always there. With that problem in mind I started reading psychoanalysis and concluded Woman’s Estate with a discussion of psychoanalysis and ideology, then eventually wrote Psychoanalysis and Feminism. After the book, I felt I needed access to the material on which the theory was built, and I trained as a clinical psychoanalyst.”

In this field, Mitchell would also break new ground—with her work on siblings. She argued that psychoanalysis had focused on the “vertical” axis of parent-child relationships to the exclusion of “horizontal” sibling relationships, and these were just as important. “It was there, and we weren’t seeing it,” she tells me. “So when I started to see it, I started to find it there, everywhere. No, not everywhere. But I found a history of it.”

She explains part of the central sibling trauma: “The older child has been attacked by the presence of the new one. And sometimes the new one will be the one who wants to get rid of the old one.” The elder sibling, meanwhile, thinks their “very existence” is under threat. Mitchell first wrote about these complex dynamics—of jealousy, of the fear of being replaced—in her history of hysteria, Mad Men and Medusas, published in 2000. Three years later, she followed it up with Siblings: Sex and Violence. In her 2023 book, Fratriarchy: The Sibling Trauma and the Law of the Mother, she showed how the positions of women—and indeed feminism—were key to understanding sibling trauma and how its effects extrapolate across society.

After lunch, Mitchell, showed me around her office, pointing out the shelf bearing research material on Bourgeois. Here, she also recalled how her innovation in psychoanalysis struck her like an epiphany. She was holidaying in France with her husband, they were writing together, and “I was sitting there looking at the sea and looking at the sunshine, and suddenly siblings dropped from the sky into my head. It came to me.”

When we meet again, some months later, Mitchell’s dark-blue plastic earrings were stark against her white hair, which brushed the shoulders of her grey-and-white striped turtleneck. We sat upstairs, in a room lined with books and filled with sunlight. Mitchell’s brother, the artist Gregory Mitchell, had recently died. His paintings lined the stairs up to the second floor. They were also arranged against a window, facing out, so that passersby on the common outside could see them. “I like to think lying down,” Mitchell said, and lay back on her sofa. Her long-time agent and friend, Candida Lacey, sat with us (later, as we discussed siblings, Mitchell encouraged Lacey to tell me about the time her elder brother tried to swap her younger brother for a puppy in Hong Kong).

Despite her years, Mitchell was as industrious as ever, and still very much occupied with Bourgeois. “My working day is working,” she told me, “and if I’m not working, I’m not happy.” Also, for fun, she was in the process of reading “the whole of Iris Murdoch”.

The Bourgeois project had hit something of a snag since we last met. A friend and colleague of Mitchell’s, Marie-Laure Bernadac, has written a biography of the artist, published in January, which draws from the same material—the artist’s notes on the psychoanalysis she underwent regularly from 1952 to 1985. “I thought, wait a minute. I’ve got to show that I’m different. So, in a sense, I’m rewriting my own book on Louise Bourgeois.”

Mitchell grows animated when she talks about Bourgeois. She clearly feels an affinity with the artist—and not just because, as she realised recently, the pair must have overlapped in New York’s Central Park in the 1980s, “when [Bourgeois] was actually talking about her own feminism there and showing her own sculptures”. When it comes to their attitudes towards fame, “I think she had the same reaction that I had,” says Mitchell. “Both of us didn’t particularly love being well known. I used the privacy of psychoanalysis to stop the well-known-ness of me in left-wing circles and feminism.” (Judith Butler, on the other hand, “is particularly good at being famous” because they aren’t “flaunting their fame in any way”.)

I want to ask Mitchell about this moment in feminism, and the idea that feminism around the world is lost, perhaps even emptied of meaning. “The history of feminism is also the history of antifeminism,” she responds, “and that’s much more interesting than global feminism.”

Seeing feminism as global is “crude” in any case, she adds. “It’s differentiated everywhere.” She notes that in Afghanistan, where the Taliban has rolled back women’s rights to naught, feminists are risking their lives: “They’re being slaughtered, and they’re now divided into people who are frightened and people who are standing out. And that’s a real and important tension, because those who are frightened are quite reasonably frightened.” She notes, too, the brave women fighting for their rights in Iran.

When she says that she is “much more interested in the concept of bisexuality in feminism”, I wonder whether she is referring to the big split in British feminism—certainly the one that takes up the most oxygen in the press—which some characterise as the trans versus women’s rights debate. She isn’t.

“I’m talking about something more interesting than gender and sex,” she says. What Mitchell means is that, even with the most fluid approach to gender (a term she thinks is more “generic” than it is useful), people are still ultimately defined by binaries.

In this, she stands in opposition to the academic Jacqueline Rose, an old friend whose work has also focused on feminism and psychoanalysis, who has argued that we are at last overcoming the man-woman binary. But “if one does go across the binary, are you not thinking in a binary way?” Mitchell asks. This question comes from the fact that society is delineated by binary prohibitions; you can or you cannot do certain things, whether that’s building a house in a particular area or committing a murder. “And it’s prohibitions you must look at, not allowances,” insists Mitchell. The idea of gender, she says, is more about allowance than prohibition, whereas it is the latter that “makes human culture”. That’s where her interest lies.

More than 50 years after the publication of Woman’s Estate, is the position of women better or worse? “It’s both. It was a such a high moment at the end of the 1960s, it was such an alive moment for women... and it was connected with the concept of the end of capitalism. Now we don’t have that high, though many of us do have more choices, of course, and many of us don’t. And misogyny is still rife.”

Feminism has officially been through two more waves since the 1960s. Mitchell says she is “stuck” with the second, with ideas about “personalising the political” and the need to think more about oppression. Still, “rather than going backwards with it”, she hopes she is “going forwards”. And it is by focusing on “the details of the present world” that she might spot what peers have missed. It is “the minutiae… the relationships between people… that tell you so much about the bigger things”.

And so Mitchell will keep thinking. She will read all of Iris Murdoch. She will write her book on Louise Bourgeois. She will go on seeing the things that others don’t.