Back in 2008, George Osborne reframed the whole way we discuss economics with a series of stern soundbites. As Lehman Brothers toppled, he buried the previous cuddly Cameronian Conservatism that had pledged to match New Labour spending totals, and instead pronounced that “the cupboard is bare” as he vowed to put “sound money” first. It took some chutzpah to blame a banking crisis on “big government,” but that’s what he did. And it worked. The stage for the long years of austerity was set.

Listening to Hammond today, you could hear the language of economics being reframed again, although perhaps not in the way that Spreadsheet Phil would have chosen. “Austerity” was out and “investment” was suddenly in, with plenty of bold talk on housing, upskilling and building hospitals—pretty much exactly the shift in tone that Labour and John McDonnell have been pushing from the opposition benches. But will the new “invest to grow” mood music alter the financial choices the government makes? That is much less clear.

This humbled and minority government has clearly decided that it can no longer afford to fixate on the (admittedly now much smaller) deficit in the way that it once did. Hammond loosened the purse strings by nearly £10bn in 2018/19, equivalent to cutting 2p off the basic rate of tax. But the score card in the Budget book suggests that the political priorities have not changed all that much.

There was, for example, a good deal of talk about putting the health service first, but almost as much money is going on freezing fuel and alcohol duties as bailing out the NHS. Instead of new welfare cuts of the sort Osborne often used to announce, there was a bit of a welfare retreat, with the long delays and harshest edges of Universal Credit eased a bit. But the money involved was only about £300m, a drop in the ocean compared to the cumulative benefit cuts since 2010 of perhaps £30bn, and small even beside various other modest giveaways, for example on business rates. More serious money, some £7bn, was earmarked for Hammond’s productivity fund, but it doesn’t kick in for several years, and he said almost nothing about how it would be spent.

One thing he did talk about a lot—both in the speech itself and in the build-up—was housing. There were promises to get Britain building again, but when I’ve heard so many of these before, under both Labour and the Tories, I’d advise against swallowing them until the experts have given the various elements of the plan a thorough going over. But what we can see is where Hammond chose to put his cash.

The chancellor talked about various guarantees and regeneration schemes, but the biggest outlay went on the Housing Infrastructure Fund, for which he earmarked about £3bn by the end of this parliament. That is almost exactly the same amount that he is preparing to forgo over the same period by cutting Stamp Duty, purportedly to help “first time buyers.” In reality, cutting taxes on property, already the most undertaxed form of wealth in Britain, will pour more fuel on the fire of the property market. It will push prices up, which will in the end help those who already own, as much as those who are locked out by prices being too high. The Office for Budget Responsibility has expressly written in an increase in house prices of 0.3 per cent on account of this policy.

If this sounds familiar, it is because it repeats the logic (or illogic) of George Osborne’s Help to Buy. It, too, promised to help those priced out of the property market, but in effect worked to push prices up. The language of Osbornomics may have gone. But the old British addiction to ruinously high property prices looks like it will be harder to kick.

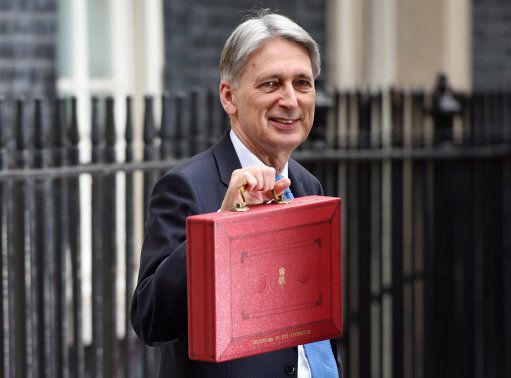

Philip Hammond’s Little Red Book

The Budget pushed the language of economics left—but tax cuts on housing suggest that the real priorities haven’t changed all that much

November 22, 2017

Photo: Joe Giddens/PA Wire/PA Images