At St Martin’s School of Art in London in the mid-1960s, Gilbert Proesch from the Dolomites and George Passmore from Somerset met, fell in love and decided to be artists together for the rest of their lives. With exceptional self-discipline they have sustained this dedication to making art as if a single person now for almost 60 years. The life of Gilbert & George is in itself by far the most extraordinary piece of performance art I have witnessed during my own time as a curator, antiquarian, writer and consumer of contemporary culture, three and four years, respectively, their junior.

In a reversal of what seemed at first a bizarre contrivance, the seamless performance of being Gilbert & George—the unchanging patterns of behaviour and speech, the matching suits, the eating every meal out because they don’t have a kitchen in the east London house they’ve lived in since the early 1970s—has come to feel simultaneously natural and surreal. It no longer matters, at least not to me, which of these opposites is true—probably both—as on none of the many occasions I have spent with them, whether discussing 1870s furniture and ceramics or sharing supper and lunch, have I observed a false step in this great double act. Theirs, it could be said, is the perfect partnership, always in public agreement, always soft-voiced, courteous and mutually supportive to each other. If one of them drinks too much at supper, the other settles the tab, calls a taxi and guides him home. Although the message on their telephone answering machine ends with “Goodbye and good riddance!”, they are considerate to others. When the older couple running the Market Café in Spitalfields—at one time their favourite eating place—came into problems with health and safety regulators, G&G paid for the necessary renovation of the entire premises and even helped out by serving at table.

They are not sociable in any conventional dinner-party sense and do not attend other artists’ exhibition previews, unembarrassed to proclaim total disinterest in any art but their own. Immediately following St Martin’s, Gilbert & George did do a couple of performances with fellow student Bruce McLean and also made a memorable artwork by serving David Hockney a meal. Gerhard Richter was another artist friend of this period, whom they met in Düsseldorf in 1970, when G&G had their first show abroad, with the influential dealer Konrad Fischer. According to Richter, they were among the first people to like and understand his landscape paintings, and in response he painted eight portraits of them from colour photographs, exhibited at Fischer’s in 1975. A pair of these Richter portraits, one of Gilbert and the other of George, are in the Tate’s collection. Another is in the National Gallery of Australia, purchased in 1976 from Fischer. The only artist whose work I have subsequently heard them praise is David Robilliard, whom they met in 1979, engaging him as one of the angry young men in the 1981 film The World of Gilbert & George. In 1984, they privately published Robilliard’s first volume of poetry, Inevitable, in an edition of one thousand. They were in constant attendance during his last days in hospital, dying of Aids in 1988, aged 36.

Indeed, Gilbert & George’s public reputation for exclusive self-focus is unjustified, as in private they are concerned and generous friends. “We of course give you full, free and non-exclusive permission to reproduce whatever you want of our work,” they once wrote to me in a letter on headed paper handwritten by George and signed by them both, the back of the envelope inscribed in large capital letters, SWALK, postwar teenage code for “sealed with a loving kiss”.

Although they and their work travel the globe continuously, with a major exhibition currently on show at the Hayward Gallery, Gilbert & George avoid the tedious waste of time that is joining the international jet set. Their loyalty is to the people connected to their home and the extensive studio at the back of the house, including the local men and boys photographed for their work. Thus when Joshua Compston, the central model for their work Naked Dream (1991), died in 1996 at the age of only 25, they attended his funeral in the Hawksmoor Church at the end of their street and were photographed paying sorrowful respect at his coffin, painted in Compston’s favourite William Morris motifs by his YBA friends Gary Hume and Gavin Turk. Previously, Gilbert & George had contributed to the Factual Nonsense exhibition HARDCORE (part 11) a framed brown envelope with the message in biro to Compston: “For Our Darling HARD-CORE with hard love + core blimey, from Gilbert & George x x. NOVEMBER 19th 1993.” (This work is now part of my recent gift of 60 contemporary works to Southampton City Art Gallery, including early pieces by Adam Dant, Angus Fairhurst, Fiona Banner, Jeremy Deller and Tracey Emin.)

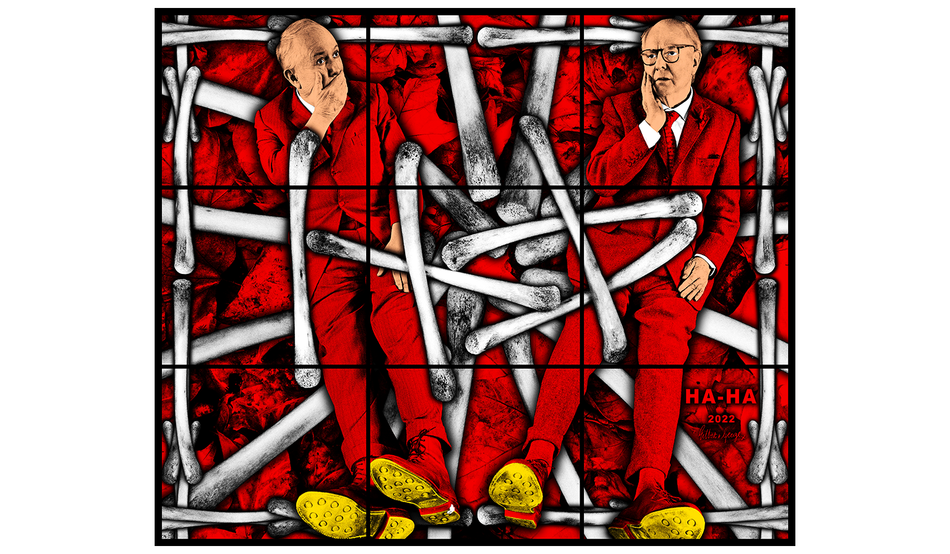

Gilbert & George’s unique fulltime double act is endlessly entertaining. On 15th October 1993, the precise day on which their combined ages added up to 100, they invited 30 friends to a nine-course dinner at a restaurant in Soho, at which nine select wines were served, concluding with a vintage Armagnac of 1893. Seated side by side, the birthday boys processed course by course around the four tables, George unsteady on his feet towards the end of the evening, leaning on the arm of a waiter. The menu and place names were decorated by hand in red acrylic and printed with a biblical quotation, from Kings 2:18, ending with the words: “…to the men who sit on the wall, that they may eat their own dung, and drink their own piss with you?” In one form or another, Gilbert & George are in all their work, the subject of which is their own life and circumstances, centred for a couple of years in the early 1970s on unrestrained drinking. They filmed themselves standing at the bar of their local pub, chatting and downing glass after glass of Gordon’s Gin until their slurred words no longer made sense. As the video ended, they both looked in danger of falling to the floor. For an invitation to the opening of their exhibition Bloody Life at the Lucio Amelio gallery in Naples in 1975, a black and white photograph of their two overlapping prostrate figures is printed in blood red.

I used to worry about the intense pitch of their life, the ceaseless effort in work and play of being Gilbert & George. In my first published writing about them, an essay in issue 14 of the quarterly art magazine Parkett in 1987, I wondered about the strain of maintaining inseparable togetherness as they grew into old age, suggesting that a practical solution might be to keep up the public performance while privately living apart in each of the identical Spitalfields houses they owned, both leading at the back onto their large studio. Yet, as far as I can tell, nothing has changed 38 years later; the extraordinary show is still on the road. Gilbert has bladder troubles and George’s balance is unreliable, requiring the constant companionship of their long-term assistant Yu Yigang, his hand resting on the shorter man’s shoulder as they go out three times a day to eat. I remain as mystified by them as on the Saturday morning in the spring of 1979, when they walked unannounced into the Victorian schoolroom in Bloomsbury where I used to run a specialist antiques shop.

Gilbert & George’s latest public statement has been to convert a textile workshop near their home into a public museum dedicated to them and their work. Opening through wrought iron gates of their own design onto a cobbled yard, there are three large galleries, a shop selling catalogues, memorabilia and tapes, as well as a viewing room. Their pride in the place was apparent when they showed me around during the building work, the attention to material detail impressive as we made a path beneath scaffold into the emerging spaces. Wearing hard hats, hi-vis jackets and steel-capped boots, G&G were unrecognisable as the living sculptors of historic invention. For a short while, we were simply three old men wandering around a building site, amiably discussing issues of light and access. That is until disrobing, when Gilbert and George again became a single person, the artist Gilbert & George.

Gilbert & George: 21st Century Pictures is on display at the Hayward Gallery until 11th January 2026