When I interviewed the artist Ai Weiwei for the March issue of Prospect, there was one thing he said that has stuck with me ever since.

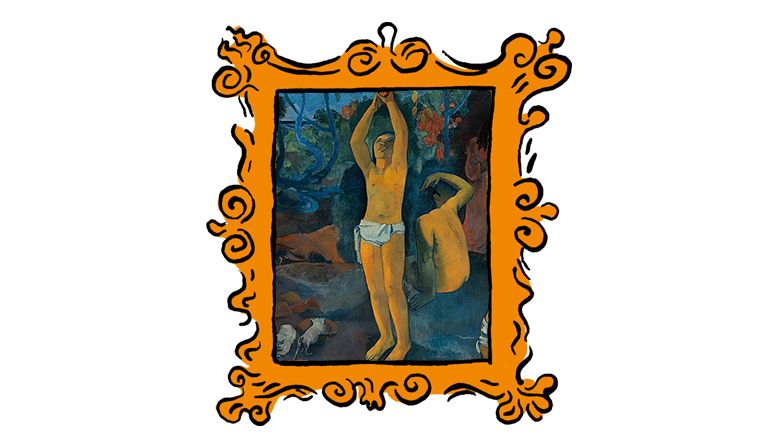

As someone better known for his affinities with irreverent imagemakers such as Andy Warhol and Marcel Duchamp, Ai surprised me when he revealed that one of his most formative influences was the postimpressionist Paul Gauguin. From the very moment he encountered his most famous work, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897–98), Ai knew Gauguin was a special artist. “I saw the painting when I was a teenager,” he told me. “And, oh, I thought, okay. He’s different from the others.” The painting’s lasting impact on him was such that, four decades later, he recast it in toy bricks, with all the typical defacements and self-references thrown in. He made it his own.

I asked him where he first saw the work, imagining a landmark exhibition of the impressionists staged at a grand national institution. Ai frowned: “I just saw copies or prints when I was in Beijing,” he said. “I don’t think I ever saw the actual painting. Just good reproductions.”

At first this sounded so strange. How could you love a painting so much without ever seeing it? Then I realised it wasn’t that strange at all. For—undergraduate musings on The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction notwithstanding—there’s one thing in Ai’s words we can all recognise: art cannot always travel, but its influence most certainly can.

And that, to my mind, is what arts journalism should be all about: a means to guide that influence beyond the vagaries and happenstance of the cultural calendar, beyond the limits of space and time which are the only real determining factors in what kind of art we get to see in the first place. (How often have we told ourselves we will see that “important” new show, only for it to completely pass us by?)

Yet, equally, it can be easy for journalism to fall short of this promise. In our overemphasis on exhibition reviews, in which individual works are reduced to being mere parts of a greater whole, we risk speaking little to the actual experience of how most of us engage with art. (To say nothing of how this underplays its innate capacity to exist in other ways, beyond the exhibition.)

It was for these reasons that we launched our regular online column “One Painting at a Time”.

The premise of the column is simple. Rather than focusing on an entire show or body of work, we take just one painting and analyse it in detail. The painting in question could be from a new exhibition or it could be sat, unassumingly, in a permanent collection. It could be relevant to what’s going on in the world right now, or it could just be somebody’s favourite picture of all time. The most important thing is that the work, for whatever reason, has ignited a spark in its onlooker. That’s the only rule; other than that, anything goes.

The result, we hope, is threefold: one, to carve out a little space in our coverage that doesn’t hinge on the contingency of exhibitions; two, to create something more self-contained than a conventional review, which by its nature can only hint and suggest rather than really show; and three, to highlight just how much life can exist in a single work, if we give it the time to be seen.

But in the spirit of showing rather than telling, let me give you some examples published since we got the column up and running just over a year ago. Last August, painter Mark Connolly chose Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 (1888) by James Ensor, a work he finds particularly captivating for its layered, cacophonous use of paint: “We can see into the cracks and spaces between the colours, into an internal space beyond the image itself.” Yet the more he takes in of this satire of Belgian politics at the end of the 18th century, he also hits on another thought: how this of all Ensor’s work, so steeped in the particularities of place, should have wound up all the way over in Los Angeles. In the end, he concludes that, really, this work ought to return to its homeland. “Ensor has a lot to give and much to teach, but to do so he needs to be seen; his work should be displayed where it commands attention.”

History is important, though one thing that’s liberating about looking at a single work is that you don’t necessarily need to take it all in at once; sometimes bringing your own experiences to the fore can be just as powerful. Back in February, Cecilia Vilela went to the Royal Academy’s recent exhibition on Brazilian modernism. While more than aware of the historic significance of the show, what really resonated with Cecilia was how much Flying a Kite (1950) by Djanira took her back to her own childhood in São Paulo: “Where I grew up, in Brazil, the blue sky of the summer holidays was always sprinkled with kites.” Mapping that experience onto the anticipatory feeling of Djanira’s work—which shows a figure preparing to send a colourful kite into the air, bystanders waiting expectantly—she manages to find a message of hope. “We don’t seem to need even the title of the painting to know that this kite is going to fly—if not by the collective force of this crowd surrounding it, then most certainly by the force of our imagination.”

Finally, in the edition that ran earlier this week, Miles Ellingham went to see the last unfinished painting by the late Edmund Fairfax-Lucy, an artist whose work has been criminally overlooked. Fairfax-Lucy was an obsessive reworker; with Still Life of a Mantelpiece and Mirror with Roses in a Jug (2014–20), he tried to recapture the same two-week period in February over six years, “when the light would come in through the window just right”. In the process, he turned what might have been an innocuous still life into something like a visual spectrum, an unphotographable image of the passing of time. “Endlessly scratched out with a razor blade and then reapplied with more paint, each work is an accumulation, an uncanny mountain.”

In Fairfax-Lucy’s unusual process is, I like to think, a neat little metaphor for One Painting at a Time overall: that every work of art contains so many different versions of itself, but it’s up to us to scrape away the layers and bring them to light. Personally, I’m excited for what our columnists might uncover next. And I hope you are, too.

The Prospect approach to painting

Through our ‘One Painting at a Time’ series, rather than focusing on an entire show or body of work, we take just one work and analyse it in detail.

May 15, 2025

Paul Gauguin’s ‘Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?’