Edmund Fairfax-Lucy was laying a carpet in his home at Charlecote Park when his heart gave out. The previous week, he’d felt a sharp pain in his chest but dismissed it. Presumably, the incident happened at the top of the stairs; nobody saw him fall, but his family found him face-up on the landing. Adorning the ceiling was a mural depicting some kind of faded battle scene and, directly above his unconscious body, there loomed a chubby, almost cherubic depiction of death. In the attic, an unfinished painting sat waiting for its creator to return: Still Life of a Mantelpiece and Mirror with Roses in a Jug.

Fairfax-Lucy was buried without a headstone in a local churchyard. It was March 2020—the start of lockdown—so only his immediate family were present at the funeral. During the ceremony, his eldest son, Patrick, got up and read a mishmash of extracts from Samuel Beckett’s Molloy (“to restore silence is the role of objects”) and TS Eliot’s Four Quartets.

“I said to my soul, be still, and let the dark come upon you / Which shall be the darkness of God. As, in a theatre, / The lights are extinguished, for the scene to be changed / With a hollow rumble of wings, with a movement of darkness on darkness.” That’s from the third section of Eliot’s “East Coker”. It’s fitting because, following the loss of Walter Sickert in 1942, Fairfax-Lucy was arguably the only other British painter capable of capturing the “darkness of a theatre” as Eliot describes. Fairfax-Lucy loved Sickert; during a retrospective he was so taken by one of the works that he approached the frame, pried a fleck of paint off the canvas and swallowed it.

Fairfax-Lucy is best known for his interiors. These were mostly dark and intentionally opaque, with stray areas of illumination defined by narrow strokes of blue—such as in his masterpiece The End of Lunch (1986–88). Yet darkness itself was never really the point. If asked about his work, Fairfax-Lucy often enthused about “the space between objects”—a space composed of light and time, what Walter Benjamin might call an object’s “aura”.

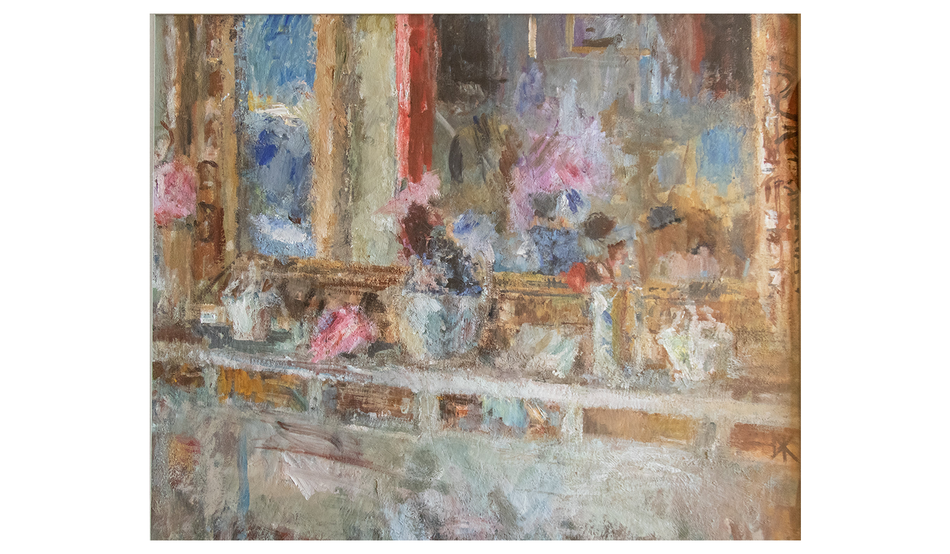

Still Life of a Mantelpiece demonstrates how Fairfax-Lucy’s work became lighter and more vibrant as he grew older. Ostensibly a still scene, it’s really a painting of two weeks in February, when the light would come in through the window just right. He became possessed during this two-week period, and each year for six years he’d endeavour to fix it to canvas. In the meantime, the roses would wilt and fall apart; sometimes he’d replace them, sometimes not. (Like Francis Bacon, he didn’t understand plastic flowers because “the whole point of flowers is that they die”.) It was common for food to rot before Fairfax-Lucy could finish painting it; his fridge was intermittently a storage facility for stinking fish muses.

The art critic Robert Hughes once said that Cezanne “painted the same motifs over and over again without ever once repeating himself”. Fairfax-Lucy did the same, but all within one painting. Endlessly scratched out with a razor blade and then reapplied with more paint, each work is an accumulation, an uncanny mountain. Up close, his canvasses disintegrate into a kind of braille. The braille is a delicate code, as Patrick tells me, “by which to read the unmaking of the flower”. Look close enough at Still Life of a Mantelpiece, and the petals and the yogurt pot on the left—barely discernible yet still retaining some mystical quality—begin to disappear.

Fairfax-Lucy was a reluctant inheritor of the British honours system; technically his full title was Sir Edmund Fairfax-Lucy, 6th Baronet, but only Wikipedia and the Telegraph’s obituary writers referred to him this way. Everyone else—including Ian Dury, who wrote a song about his garden—knew him as “Ed”. In 1946, Ed’s father Montgomerie gave Charlecote to the National Trust. In the 1980s, Ed was allowed to move back in, though the house remained open to the public. He was confined to a dusty quarter of the building where he eventually raised a family. His two sons grew up with geriatric tour groups peering in at them while they ate breakfast.

“I don’t know, at some point the will to live just reappeared,” Patrick says after taking me to see his father’s grave earlier this month; we couldn’t unlock the gate to the yard and had to climb the fence. Then we broke into the church. Having moved back home to Charlecote, Patrick suffered an almost fatal bout of depression. Occasionally, he ventures into the part of the estate run by the National Trust where sightseers stare at his dad’s work. As we speak, Patrick’s brother, Johnny, is back at the house desperately trying to finish his dissertation before the deadline. Both of them look like Ed.

Before leaving, I catch a National Trust volunteer describing Still Life of a Mantelpiece to some visitors. “Clearly it’s in the impressionist style,” he explained to a yawning couple. I can see what he means, but I also disagree. The impressionists were motivated by representing one present moment, but Still Life of a Mantelpiece is more expansive than that. It is every present moment, endlessly renewed, forever enchantingly dying and growing brighter every day.