As I write this, the 80-year-old author Boualem Sansal, who suffers from prostate cancer, has been sitting in jail for almost nine months.

An Algerian who writes in French and lives in France, Sansal has been a major figure of the francophone literary scene for a few decades. Since his first books, which tried to make sense of the civil war that devastated Algeria in the 1990s, Sansal’s works have revolved around Algerian politics and criticised religious extremism. His 2084: The End of the World, a dystopian novel in which all of society is ruled by a religion not unlike Islam, was awarded the prestigious Prix de l’Académie Française. (I read it a good ten years ago; I found it boring as hell, a bastard offspring of Houellebecq’s Submission and Orwell’s 1984, minus the fun—but that’s not the point.)

The reason Sansal lies in prison, however, is not his fiction. Over the years, the writer has become a prominent voice on the French right, openly criticising political Islam and contributing to conservative publications such as Le Figaro. On 2nd October last year, he stated in an interview that parts of today’s Algerian territory used to belong to Morocco before the French colonised the area in the 19th century.

What may seem like a benign remark was enough to land the author in jail. The border between Morocco and Algeria has been fiercely debated between both countries for decades, and Sansal’s words were seen as an endorsement of Morocco’s stance on the subject. The writer was arrested, during a trip to Algiers, on the grounds of “endangering national security”.

The Algerian government was never famous for a liberal approach to freedom of speech. In Sansal’s case, however, there is much more involved than just domestic policy.

The summer before he was arrested, Sansal received French citizenship—which effectively turned him into a means for Algeria to put pressure on the French government. Diplomatic relations between the country and its former coloniser are notoriously strained and have been particularly difficult over the past year. From French president Emmanuel Macron publicly endorsing Morocco’s claims on Algerian territory to reciprocal threats regarding visa deliveries, an already tense situation has been getting tenser.

This is not the first time the Algerian government has trampled over a writer’s rights as part of its argument with France. Kamel Daoud, another French-Algerian author, was awarded the 2024 Prix Goncourt—France’s highest literary distinction—for his novel Houris. It is set during the Algerian civil war and tells the true story of a woman who lost her voice when armed men slit her throat and left her for dead. After the book was published, Daoud and his publisher, Gallimard, were prevented from entering Algerian territory; writing about this bloody period of recent history is purely and simply forbidden.

Sansal was next—and, on 27th March, he was sentenced to five years in prison. At his age, and given his medical condition, this is the equivalent of a death sentence.

What’s surprising, however, is not so much Sansal’s incarceration, nor even the parlous state of freedom of speech around the world. No, it’s the uneasy silence that surrounds these events on the French side of the Mediterranean.

The French left has long been outspoken in its advocacy for freedom of speech; it’s been part of their DNA for over two centuries, dating back to the French Revolution. Sansal, however, is a conservative, and the interview that led him to being arrested was published in the far-right magazine Frontières, which he cofounded. This, it seems, is enough for the left to consider him unworthy of political support.

While a few intellectuals initially defended the writer, embarrassment around his case has since caused them to lapse into silence. Wherever attempts have been made to act, no matter how minor, the left has remained impressively unsupportive. In May, for example, the French parliament voted on a text asking that the writer be immediately released; the initiative was largely symbolic, but far-left party LFI still voted against it, arguing that this would mean instrumentalising Sansal’s life for political purposes. It did not seem to dawn upon them that this was precisely the point of his being arrested.

In the country that saw the staff of satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo slaughtered ten years ago, this lack of support for Sansal is a disgrace.

After they died, Charlie Hebdo cartoonists were acclaimed as heroes by politicians who would only ever mention them with disdain while they were alive. Many shed ostentatious tears when remembering artists who, before the attack, were widely considered a national annoyance. Putting the dead on a pedestal is convenient: unlike the living, they can’t disagree.

A decade on, the slogan “Je suis Charlie” has fallen out of fashion and is now slightly embarrassing, like the music you were listening to when you were 13. We can only wish that all those politicians who were so quick to support Charlie Hebdo in 2015 would do the same for Sansal today. But it’s one thing to hail the dead as martyrs; quite another, it seems, to stand up for them while it’s still time. It turns out that freedom of speech, and the defence of it, is a seasonal thing.

After the Charlie Hebdo journalists were murdered, councils named streets after some of them. While that support was welcome, it came too late. And I can’t help wondering whether Boualem Sansal will know the same fate: being largely ignored while alive and in trouble, only to be feted once he’s dead. When you’re an 80-year-old with prostate cancer sitting in prison, these things can happen quickly.

And, quite frankly, the signs aren’t great: councils have already started renaming streets in Sansal’s honour.

Boualem Sansal is still in jail—and no one cares

The 80-year-old writer has been locked up in an Algerian prison for nine months. Where are the defenders of free speech now?

August 14, 2025

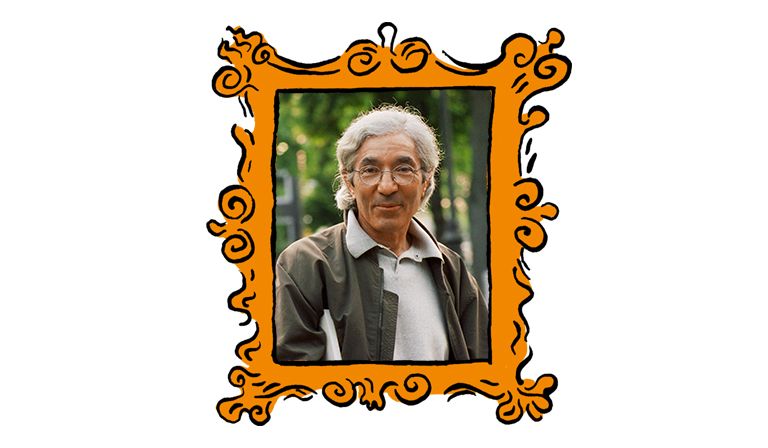

Boualem Sansal in 2009. Image: Interfoto/Alamy