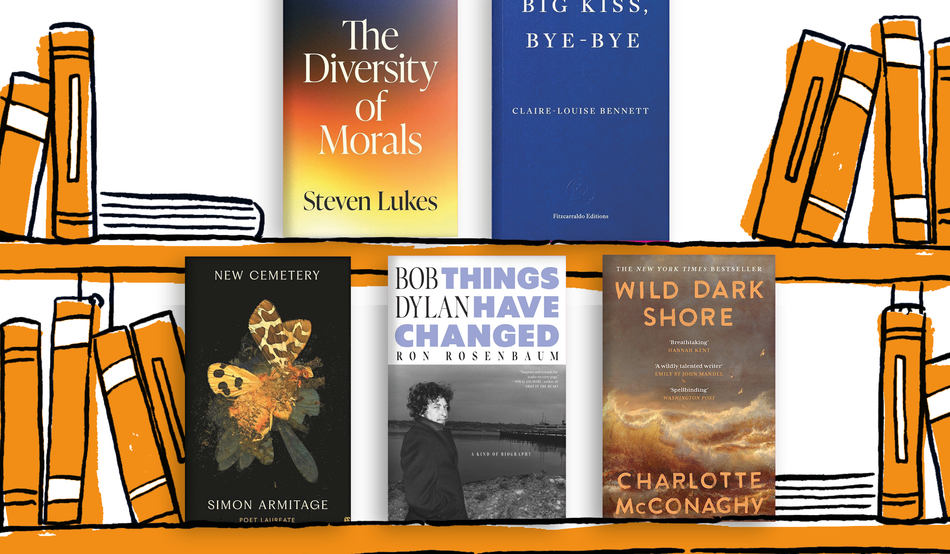

New Cemetery

by Simon Armitage (Faber, £14.99)

In later life, WB Yeats saw himself as “a sixty-year-old smiling public man” still driven by the passions of a young poet. Simon Armitage was once a youthful voice too: his acclaimed first books were called Zoom! (1989) and Kid (1992). But now he is 62 and poet laureate, writing smiling public haiku for the National Trust, as collected in his last volume, Blossomise.

In New Cemetery, however, he joins Yeats to rummage again in the “rag and bone shop of the heart”. These are his own, uncommissioned poems, composed over the last decade as he watched the local council build a graveyard on fields at the top of his road in Yorkshire. Many describe working from home, in Zen-like meditations on the mortality of nothing much, such as a ballpoint “striped / with the faded name / of a Munich hotel”.

The tweezer-like, three-line stanza Armitage employs is ideal for these reflections unpicking how the world is made—an aesthetic that might be called Deep Dad. There are some lovely ones (really) in praise of the Velux skylight above the poet’s desk: “glass planchette / elbowing / cloud-edge and cloud-base // onto a scrawled page”. And the poems on the death of his own dad are particularly moving, even if one stanza is simply the classic male conversational gambit of naming roads (“M5 / M6 / M62”).

At 100 pages, New Cemetery is less a long poem and more a landscape of small ones, some slighter than others. It doesn’t have the self-lacerating Yeatsian energy of LX, the ingeniously rhymed sonnet sequence Armitage published for his 60th birthday (“My soul said ‘I guess I was lucky… a la-di-da laureate / I could have ended up in a laundrette’”). But his mordantly humorous feeling for life—and death—is undiminished.

Jeremy Noel-Tod

The Diversity of Morals

by Steven Lukes (Princeton UP, £25)

What are we talking about when we talk about morality? Steven Lukes tackles this question by richly combining sociology, his own discipline, with philosophy, anthropology, history and political theory.

Philosophers, he says, tend to follow Hume, in treating morality as a timeless, unitary—if differently realised—phenomenon of which we have somehow-uniform “intuitions”. Social scientists follow Herder in celebrating each culture’s different, incommensurable “standard of perfection”, but they therefore face the problem of articulating what such a diversity of morals is actually a diversity of—how do you distinguish moral values and rules from customs, conventions, etiquette, or from what is simply immoral?

Surely, argues Lukes, a key feature of any morality is its aspiration to universality. In the “Axial Age”, between the 3rd and 8th centuries BCE, there was (it is generally agreed) a parallel emergence of religious and philosophical thought in different countries worldwide. Like other species (Lukes cites various primatologists), humans had a limited range of altruism, and they now began to transcend the tribal mentality of “us versus them” into a sense of a common humanity.

Lukes also appeals to Adam Smith, who wrote of our innate sensibility to others’ sorrow and of how everyone, even villains, senses “the man within the breast, the… ideal spectator of our sentiments and conduct”. Perhaps, thanks to the evolution of this judicious empathy, “what counts as right and good, as obligatory and admirable, as human and inhuman, [is] internal to varying and incompatible moral frameworks”.

Lukes admits that, because our current multicultural societies no longer have the separate horizons envisaged by Herder, the potential amount and depth of polarisation within them is exacerbated; but he is somehow hopeful. Moral Relativism, his recent book, was a classic. This, although full of insights and erudition, is almost too irenic.

Jane O’Grady

Bob Dylan: Things Have Changed

by Ron Rosenbaum (Melville House, £25)

“You been talkin’ to Ginsberg?” Bob Dylan rasped when Ron Rosenbaum interviewed him for Playboy back in the late 1970s. Rosenbaum’s sin was to have “deconstruct[ed]… in four-and-a-half minutes” the four-plus-hours rough cut of Dylan’s directorial debut Renaldo and Clara it had been insisted he sit through the day before their meeting. Taking journalists down a peg is standard practice for Dylan, of course. But since one of the abiding themes of Rosenbaum’s new book, Things Have Changed, is Dylan’s life-long anti-intellectualism, he should surely have known not to harp on the movie’s frequently ponderous mystical ramblings and go in big on, say, Howie Wyeth’s drumming.

The first thing to be said about Rosenbaum’s book is that, though it is subtitled A Kind of Biography—at least it is on the dustjacket; inside it’s called A Sort of Biography—it is far from being yet another life of Bob. (I don’t know whether Things Have Changed started life as the Dylan biography Rosenbaum was for several years meant to be writing for Yale, but if it did, they had every right to reject it.) Instead, it zones in on what might be Dylan’s ur-theme—the illusory nature of the unified self.

Alas, like so many Bobolators before him, Rosenbaum wants only to discuss Dylan’s lyrics. Though he more than once tells us he’s proud to have been the reporter to whom Dylan worried he would never again find “That thin, that wild mercury sound” of his mid-1960s masterpieces Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde, Rosenbaum has no interest in commenting on Dylan’s various soundscapes. Indeed, at one point this soi disant “good little English major” dismisses musicological analysis for being “crippled [by] subjectivity”.

But if his insights are narrow, his interests are wide. You finish the book vowing to listen again to a dozen and more Dylan songs not normally regarded as classics.

Christopher Bray

Wild Dark Shore

by Charlotte McConaghy (Canongate, £19.99)

Climate fiction can be a hard sell. Who wants to sink into an eco-disaster novel when we are living the reality? But with high stakes comes the potential for high drama. In her third novel, Charlotte McConaghy stretches plausibility to examine how we might react when pushed to extremes—of temperature, weather and living conditions—on a small, subantarctic island.

Rowan is drowning when she washes up on Shearwater during the worst storm Dominic Salt and his three children have endured in the eight years since the widower took a caretaker job on the tiny island. A face flashes into Rowan’s vision: “His face, a return. A drowning,” writes McConaghy, setting up a mystery from the outset. Fen, Dominic’s teenage daughter, spots Rowan “draped upon a tangle of driftwood” and drags her ashore.

With some judicious nursing, Rowan survives, her mysterious arrival triggering a family reckoning and coinciding with crunch time for the Salts and Shearwater Island, which is itself drowning under rising sea levels. While McConaghy’s two previous novels were about the fate of animals, it is seeds that are under threat here: the fictional Shearwater is home to the world’s largest seed bank. The Salts are the island’s last inhabitants; a ship is coming in six weeks to evacuate them and as many seeds as they can salvage before melting permafrost floods the storage vault.

McConaghy, who switches between first- and third-person points of view to tell her story, goes all in with intrigue, melodrama and more pathetic fallacy than a Key Stage 2 English lesson, but somehow it all works… just. The strength is in the detail: Shearwater is based closely on Macquarie Island, a World Heritage Site, where McConaghy travelled for research. Sparks fly as the pace accelerates in the last 50 pages; I read into the small hours, gripped by this atmospheric addition to a growing genre.

Susie Mesure

Big Kiss, Bye-Bye

by Claire-Louise Bennett (Fitzcarraldo Editions, £12.99)

At the start of Claire-Louise Bennett’s incandescent new novel Big Kiss, Bye-Bye, the unnamed narrator—an author—and her ex, Xavier, “are no longer in touch”. She has moved to rural Ireland without telling him. But that doesn’t stay the case for long in a will-they-won’t-they romance that explores what it means to see another person “correctly”—or, rather, “see into them deeply, right to the core, and know them better than anyone else”.

Bennett embarked on similar projects with Pond (which used a woman’s everyday life as a launchpad for near-transcendent ruminations) and Checkout 19 (a revelatory künstlerroman relaying a woman’s coming-of-age through reading). This time, the thread by which the book hangs together is the failed loves that make up one’s personal history.

Its pages contain a catalogue of disappointing men. There is, of course, Xavier, a needy former banker who once “kept staff”—now in his seventies, he is about to go into a care home and the narrator no longer desires him; then Robert Turner, a philosophy teacher whom she had “dealings” with at school, since realising that he “behaved very badly”; “the coward”, who is married but pursues her anyway; and other troublesome minor players, who have even broken into her apartment. Sketched out in rambling, roundabout prose, these characters begin to blur into one.

Though it intersperses sensual passages with witty musings on everything from bouquets of flowers to satanism, the novel is more coldly restrained than Bennett’s previous work. Like the narrator’s romantic encounters, the book is not quite satisfying as an exploration of the fragility of desire. But it takes flight in moments grounded by female friendship and has flashes of brilliance.

Miriam Balanescu