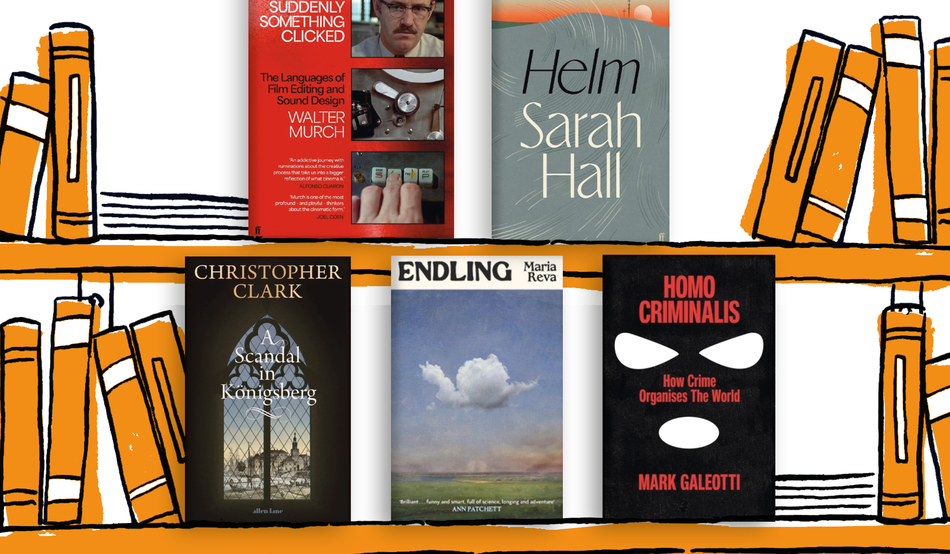

A Scandal in Königsberg

by Christopher Clark (Allen Lane, £22)

Christopher Clark’s last book, Revolutionary Spring, about the upheavals of 1848, was almost 900 pages long. His magisterial account of Europe’s descent into the First World War, The Sleepwalkers, was over 700 pages. His history of Prussia, Iron Kingdom, topped 800 pages.

But what is this? Clark’s latest book, A Scandal in Königsberg, is a mere 177 pages, or more like 150 if you take out the back matter. Publishers have clearly stopped paying Cambridge’s regius professor of history by the inch.

Or, rather, here is a signal lesson on why you should never judge a book by the number of pages between its covers: there is actually a lot going on in A Scandal in Königsberg.

Let’s start with the scandal itself. It took place in the Prussian city of Königsberg (now part of a Russian enclave squeezed between Poland and Lithuania, known as Kaliningrad) in the 1830s and concerned two Lutheran preachers, Johann Ebel and Heinrich Diestel, who were accused of corrupting young women with their progressive ways. The accusations involved some of the finest families in Königsberg and lots and lots of sexual impropriety.

Were these charges correct? Judging from the evidence that Clark has carefully excavated from various archives, no—they were almost certainly the lashings-out of jealous, hypocritical men. But while A Scandal in Königsberg defends Ebel and Diestel, it is more interested in what their case reveals about the rise of the media, the birth pangs of liberty and even the tension between reason and imagination. Its plot of history is small, but its horizons are enormous.

And so, too, is its emotional sensitivity. Clark ends the book by dwelling on the “good people [who] were sucked into the maelstrom… women steadfastly defending themselves against impertinent and deeply offensive lines of questioning”. History can be many things: enlightening, entertaining, salacious. But it is also, A Scandal in Königsberg seems to emphasise, a thing that happens to real people.

Peter Hoskin

Suddenly Something Clicked: The Languages of Film Editing and Sound Design

by Walter Murch (Faber, £30)

For over 50 years, Walter Murch has been the technical backbone of numerous films, including some of the very greatest. The son of a magic realist painter, he inherited his family’s artistry in his composition of motion pictures. And with his latest work, Suddenly, Something Clicked—which is textbook, autobiography and insanity all in one—he pulls back the curtain on that craft.

The book is split between sound design and film editing, Murch’s main areas of expertise. And its structure echoes his signature editing style, favouring emotional rhythm over strict chronology. So we flit from his view of editors as surgical gardeners to his re-edit of Orson Welles’s studio-interfered Touch of Evil (1958) to, of course, a seven-page interview with a sentient sound effect.

It’s impossible to discuss Murch without touching on his longtime friend and collaborator Francis Ford Coppola. The book’s second part opens with the latter’s accidental aerosol macing of the post-production suite for their 1974 film The Conversation. The making of Apocalypse Now (1979) also happened in strange, strained circumstances—it’s disclosed here that the sound mix took place in an abandoned sweatshop, on Coppola’s insistence—but Murch also draws attention to the quiet moments of genius, such as how, taken together, Willard’s narration and Kilgore’s recording of “Flight of the Valkyries” are intended as acoustic inhabitations of the characters’ souls.

These are mere gestures towards what Suddenly, Something Clicked offers; much like the masterpieces Murch has post-produced, it really has to be experienced first-hand. Towards the end, he teases what’s to come—apparently, this book only covers “40 per cent” of his original manuscript. Bring on another apocalypse.

Teddy D'Ancona

Homo Criminalis: How Crime Organises the World

by Mark Galeotti (Ebury, £22)

We are all homo sapiens, but are we all really so sapiens? There are some who would say that the current occupant of the White House isn’t much wiser than, say, a pan troglodytes or even a lumbricus terrestris.

Which is why the title of Mark Galeotti’s new book, Homo Criminalis, carries immediate appeal. And so does its thesis: that the criminal underworld has had—and continues to have—more influence on our seemingly respectable upperworld than we generally care to admit. Now that really does sound a bit more like Trump and his gangster presidency.

Galeotti’s previous books have focused on Russia and its organised criminals, so he knows whereof he speaks. Indeed, he writes here that “it is Vladimir Putin’s Russia which seems to have most clearly identified the way a state can use crime not simply as a means of support, but as a weapon”—citing everything from its cyberattacks on other countries to its use of contract killers for political murders.

But Galeotti also takes us beyond Russia—and the present day. The book starts with the eunuch bandits of 17th-century China and soon bounds to Norman England, Ancient Greece and dozens of other times and places. Did you know that tax collectors in pharaonic Egypt used to rig their scales to cheat farmers out of produce? Or that the martial art of capoeira was pioneered by the knife-wielding gangs of 19th-century Rio de Janeiro?

All this is great fun but also sobering—especially when you realise that, under Galeotti’s schema, we’re all complicit. In an age of interconnectedness and cryptocurrencies and environmental hazard, there is barely a single transaction that hasn’t been touched by crime somewhere along the line. Maybe, in the end, Trump isn’t the only one who doesn’t deserve to be called sapiens.

Peter Hoskin

Endling

by Maria Reva (Virago, £20)

Yeva is a misanthropic, maverick malacologist dedicated to saving as many dying species of snail as possible, “humble victims of the Earth’s sixth mass extinction”. She lives and works in the campervan that’s also her laboratory, the funding for which she earns by dating western men who’ve come to Ukraine—both a breadbasket and “a bride basket”—searching for biddable life-partners.

Also on the books of the “Romeo Meets Yulia” romance tour agency is 18-year-old Nastia. She and her sister/interpreter, Sol, have ulterior motives too. Their mother is a well-known activist in a Pussy Riot-esque protest group, and Nastia’s now planning a headline-grabbing action of her own.

Soon, the three women are barrelling through the Ukrainian countryside with a lab full of kidnapped bachelors, while also on a desperate mission to find a mate for one of Yeva’s beloved snails, all at the exact moment that Russian forces mount their invasion…

The war doesn’t just interrupt the women’s best-laid plans, it’s a formal intrusion into the narrative itself. The author—who was born in Ukraine but today lives in Canada—becomes a character in the novel, pontificating about the right and wrong ways to write about the unfolding of history, worrying about her family members back in Ukraine and trying to work out what she should be writing about: “What right do I have to write about the war from my armchair?”

Unfortunately, these metafictional manoeuvres throw everything out of balance. What should be experimental and exciting actually just confuses matters. And while I understand that this is Reva’s point—pit a comic heist against the realities of active combat and an inevitable schism appears—it’s not enough to save the novel from its floundering second half. One of the weaker members of this year’s Booker Dozen; I’ll be surprised if it makes the shortlist.

Lucy Scholes

Helm

by Sarah Hall (Faber, £20)

The English novelist Sarah Hall has a taste for dark futures. A flooded Britain falls prey to a misogynist junta in her 2007 novel The Carhullan Army; in 2021’s Burntcoat the country is overrun by a virus liquefying its victims from inside. Added to this widescreen imagination is a poet’s eye: Hall’s finely wrought sentences are as pressurised as her scenarios, electric with word choices that startle and delight.

Hall’s 10th book, Helm, unfolds as a mosaic of episodes involving a dizzying range of characters in her native Cumbria, from a Stone Age herdswoman and a medieval warlock to a climate scientist and a traumatised ex-cop, all of them overseen by the titular northeasterly wind that is the novel’s unifying presence, overseeing its millennia-spanning panorama of humanity in a series of playful interludes.

Keeping track of the storylines is taxing, since we stick with no character for more than a few pages at a time. Yet the hopscotch form gives Hall a way to track incremental environmental change—the novelistic equivalent of time-lapse footage—while letting her use her talents as a miniaturist at larger scale (the author of three story collections, Hall is the only writer to have won the BBC National Short Story Award twice).

Besides the vast scope and imaginative courage to plunge into the nitty-gritty of disparate experience, what really makes Helm tick is the endless creativity of the diction, by turns rugged, sensual and mischievous, sometimes all at once; I don’t ever recall seeing “spigot” used the way it is here, during a scene of alfresco congress in a hot air balloon. If we sometimes lose sight of the characters, maybe that’s part of the point of a novel that puts the elements centre stage.

Anthony Cummins