It is a cliché—perhaps also a truism—that you should never meet your heroes. But how about writing a biography of them? Attempting a life of the musician, actor and one-time rock ’n’ rollin’ bitch David Bowie is the third time that I have done so for a personal idol. The first occasion was 2014’s Blazing Star, a modestly revisionist biography of the libertine poet Lord Rochester; I argued that he wasn’t nearly as bad as posterity had suggested. Two years later, I attempted the opposite perspective on the other aristocratic versifier, Lord Byron, in which I suggested that he was in fact worse than reputation held, being a grubby sex pest who was capable of hideous acts that were in no way excused by his considerable personal charm.

Neither Blazing Star nor Byron’s Women changed many minds, I fear, but they gave me a taste for the provocative. Yet when it came to Bowie, I was afraid of what I would discover if I raised the figurative rock. Would there be all manner of licentious creepy-crawlies underneath? The #MeToo era and cancel culture have not been kind, reputationally, to many of the musicians who once dominated the industry, and the possibility of some grim discoveries was inevitably a concern when I came to write about the erstwhile Ziggy Stardust. There have been repeated claims about sex with underage groupies in the 1970s, and although Bowie was hardly alone in this regard, that does not excuse the unsavoury nature of the (admittedly unsubstantiated) accusations that have been levelled against him posthumously. But there were other worries, too. Before now, I had abandoned several other biographies of people I admired, often because there wasn’t a book to be written about them. Would Bowie—one of the most documented figures of the 20th and 21st centuries—really justify a new life?

It seemed clear that there was only one angle left to explore, and that was not Bowie the shape-shifting 1970s gender-bender, nor indeed his brief, unlikely heyday in the early 1980s as the world-conquering Let’s Dance pop icon. Instead, I was more interested in the latter half of his life and career, as Bowie—once a figure who seemed to exert near-total influence over the music industry—became, all over again, the man who fell to earth. After the complete dud of 1987’s Never Let Me Down, he buried himself in the equally unsuccessful debacle of Tin Machine, an American-accented hard-rock band that saw Bowie pretending to be “one of the guys”.

He later claimed that he threw himself into the project to reignite his creative fire. It worked, up to a point, but only insofar as he realised that even his distinguished reputation could not survive another disaster of that kind. Yet I remembered another detail from that time: Bowie visiting his family home in Brixton in 1991, when the Tin Machine tour bus arrived there for a gig, and being reduced to tears, unable either to comprehend the good fortune that he had enjoyed in his life or the depredations of fashion that had led to his presently reduced circumstances. The image of the musician standing on an undistinguished South London street, weeping, seemed the perfect way to begin the book, just as his departure from the world to the strains of his final album, the near-mythic Blackstar, gave it an obvious ending. Deciding what would come in between was the harder part.

The problem with the narrative of Bowie’s return to critical and commercial success, only arrested by inconvenient mortality, is that it is not a straightforward tale of a plucky underdog regaining his rightful place in the Valhalla of musical stardom. Many would argue that he never salvaged the giddy genius of his heyday, and they may have a point. Estimable albums such as The Buddha of Suburbia (1993), Outside (1995), Heathen (2002) and, of course, Blackstar (2016) are seldom talked of in the same breath as Ziggy Stardust (1972), Station to Station (1976), Low (1977) or Scary Monsters (1980). As for the individual songs, well you can make a case for many of them, but they simply aren’t the equal of “Heroes”, “Life on Mars” or “Ashes to Ashes”. Only a delusional fool would attempt to make such a case.

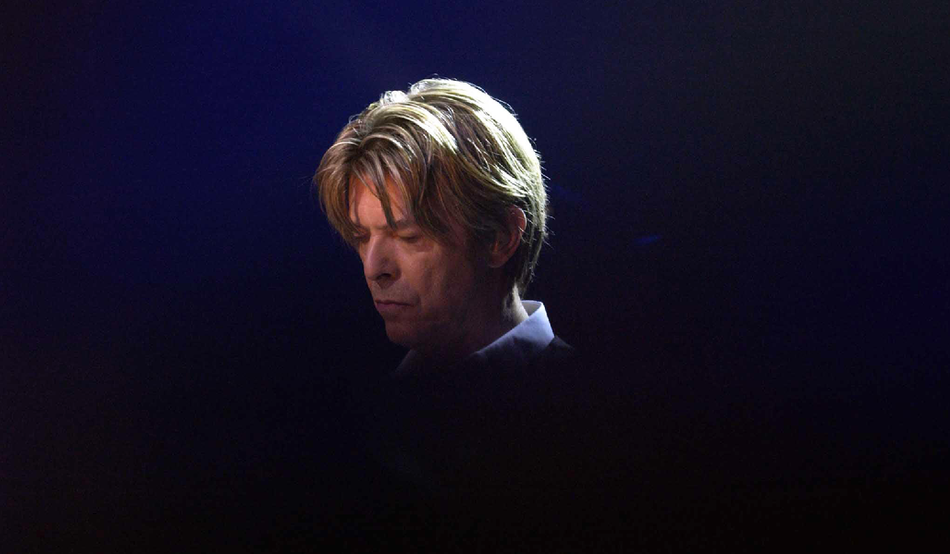

Many would argue that Bowie never salvaged the giddy genius of his heyday

Paging Mr Delusional. I was fortunate enough to find an editor, in the form of New Modern’s Pete Selby, who was not only as paid-up a Bowie fan as I am, but who understood the project and what I was attempting to do. A deal was struck, publication date agreed—January 2026, naturally, given the anniversary of Bowie’s death on the 10th of the month—and I began my research. It would be a significant change of pace from my earlier historical biographies in that many of the people who worked with Bowie during the period I wished to write about were alive and about. They had also been underexploited by other writers, who preferred to speak to other well-known figures from Bowie’s past, including musicians such as Rick Wakeman (who famously played piano on “Life on Mars”) and the producer Nile Rodgers, who triumphed with Let’s Dance (1983) only to stumble on Black Tie White Noise (1993) because of Bowie being dictatorial. By talking to lesser-known men and women who played with him in the 1990s, and beyond, I was convinced that they would have invaluable, never-before-heard stories.

A wish-list of interviewees was drawn up, with Tony Visconti, Bowie’s long-time producer, Mike Garson, his genius keyboardist and one of the Spiders from Mars, and Reeves Gabrels, his most consistent collaborator throughout this later period, right at the top. Having interviewed the forthcoming and warm Visconti previously for another piece, I foresaw no difficulty in obtaining another interview. And then an iceberg of sorts appeared. Casually emailing the producer in near-assurance that he would play ball, I was stunned to receive a formal reply not from him but his agent, informing me that commitments to Visconti’s own memoir—which would cover much of the period I was writing about—meant that he was not cooperating with any rival projects.

For a night, I considered jacking in the whole thing. After all, if I couldn’t get the interviewees I needed, the book would be nothing more than a cuttings job. I had no serious expectation that I would be speaking to the likes of Ricky Gervais, Tilda Swinton and Christopher Nolan—all late-era Bowie collaborators—despite my best efforts, so the loss of Visconti’s input was a blow. Then I reconsidered it pragmatically. While the previous conversation we’d had had been about an entirely different era, he had been generous in his observations about his working relationship with Bowie and his later reconciliation. Belying the usual stories that he and the singer had become estranged, he told me “David and I never fell out. We gave each other permission to work with other people.” Even with just these small, telling details, it was a start. So then it was time to begin contacting musicians, filmmakers, biographers and publicists—and hope for the best.

Those who had worked with and loved Bowie were happy to discuss their collaborations and spoke generously of their time together. Over and over again, the same attributes were brought up, quite independently: Bowie’s sense of humour; his thirst for books; his penetrating intelligence; his kindness and personal decency, most clearly seen in his love for his family and loyalty to collaborators; and his relentless, questing desire always to move onto the next project, which saw him dispense with these collaborators less out of callousness and more because he wished to explore new worlds with new shipmates, with the old ones left safely behind on shore.

His personal decency was most clearly seen in his love for his family and loyalty to collaborators

One long-term first mate who kept returning for fresh adventures was keyboardist Garson, whose wonderfully warm—at times even emotional—recollections of Bowie form the centrepiece of Lazarus, as my book was eventually, inevitably titled. Another was Gabrels, whom I tracked down in a spirit of discovery that would have done credit to Marlow in Heart of Darkness. Email addresses gave only bounce-backs, telephone numbers had been disconnected, and I had almost given up hope when one day I received an email saying, “Hi, this is Reeves. I understand you want to chat to me about Bowie?”

The musician proved not to be a Mr Kurtz, but a wonderfully witty, endlessly revelatory interviewee who was both pragmatic and wry about his years spent with Bowie, and the regrets he had over his decision, as he put it, to be “the only guy who ever quit working with [him] rather than being fired”. He spoke movingly of his long friendship with Bowie, saying that “Today, I have evolved emotionally enough that I would have been more demonstrative of how much I appreciated the previous 14 years.” His warmth, and candour, made our conversations a pleasure.

But there were many others, too, whose input made the book what it is. And now, writing in the immediate aftermath of its publication, I can finally assess Bowie in the round. Despite my love of much of his music, I was uninterested in writing a hagiography of a man who was certainly not flawless. He was capable, as one musician put it, of being “a shitty, pissy little asshole”, and I am still faintly surprised at how poorly he emerges from the first third or so of the book, as grand scheme after grand scheme fails and he retreats into over-compensatory high-handedness. The Tin Machine project fizzled out ignobly, and several of his albums simply don’t work; I won’t be rushing to listen to Black Tie White Noise or the dismal drum ’n’ bass experiment Earthling (1997) again any time soon. Yet he was also a genius, in the true sense of the term. As his innate talent began to win out after the desperate attempts to keep up with the (David) Joneses, he recaptured the glories that he had demonstrated earlier in his career.

A near-fatal heart attack in 2004 stopped his momentum, but not his creativity, and by the time he returned with the greatest comeback albums imaginable—The Next Day (2013) and Blackstar—he had reasserted his primacy all over again. Even such a thing as death could not entirely halt his stride, nor dim the passion that so many continue to feel for him. Occasional bouts of shittiness and pissiness notwithstanding, it has been a pleasure to follow in Bowie’s footsteps. All I can hope is that those who take the journey with me will feel the same way too.

Lazarus: The Second Coming of David Bowie is available now (New Modern, £25)