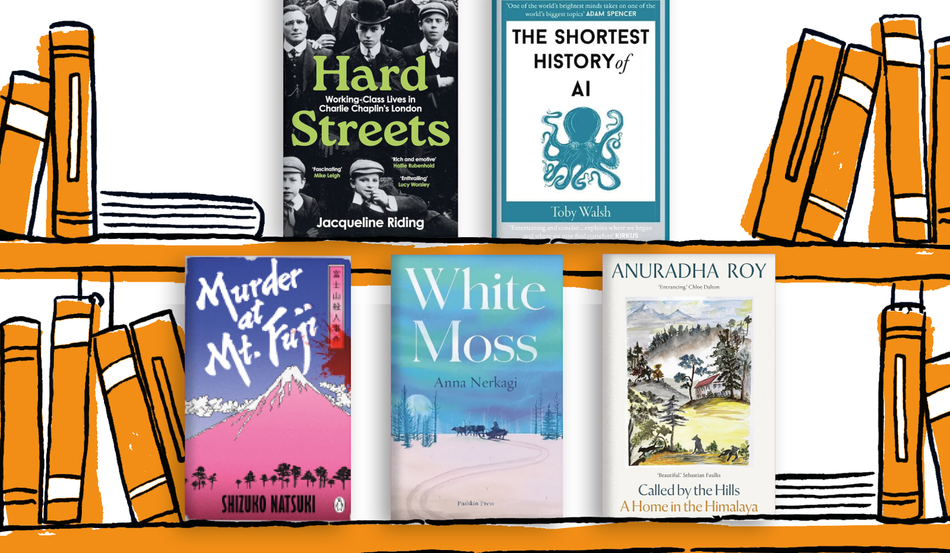

Hard Streets: Working-Class Lives in Charlie Chaplin’s London

by Jacqueline Riding (Profile, £25)

If you walk down London’s Walworth Road, a mile-long stretch that goes from Elephant and Castle to what might loosely be called the city’s southeast, and then pause on the corner of East Street, where a market has been situated since the late 19th century, you’ll see a plaque above a sports shop. It reads: “Charlie Chaplin, 1889-1977, Walworth-born comic genius.”

The vagueness of the plaque is surely intentional and, in its own way, wise—since no one has ever quite nailed down, to a specific house or site, where the great silent filmmaker came into the world. His own autobiography mentions only “East Lane”, though some doubt even that, seeing as there is no birth certificate to confirm the truth. All we really know is that Chaplin was a creature of the porous London boroughs of Lambeth and Southwark, an area of some poverty now, but excruciating poverty during his childhood.

It is this territory that Jacqueline Riding roams across in Hard Streets—though no one can accuse her or it of vagueness. Taking as her subject “working-class lives in Charlie Chaplin’s London”, the cultural historian gives us a clear—and, crucially, clear-eyed—picture of those left behind, or run over, by the upheavals of empire, industry and science around the turn of the 20th century.

Of course, there is misery, often passed down generations: we read here of workhouses, petty crime, sickliness and Chaplin’s grandmother’s confinement in Banstead Asylum. But there’s also defiance and joy: Keir Hardie speeches, proud flowerpots, raucous music halls. What other mix would we expect of the streets that produced The Tramp?

Except those same streets also produced others. Perhaps the main flaw of Hard Streets—though it is an understandable one, and no fault of the author—is the focus on Chaplin in its cover image and subtitle. The autography of another “local-boy-made-good”, the ceramist George Tinworth, underpins perhaps even more of Riding’s text. Where’s his plaque, I wonder?

Peter Hoskin

Called by the Hills: A Home in the Himalaya

by Anuradha Roy (Daunt Books £12.99)

I went to a boarding school in the Himalayan foothills from where we were sent out trekking twice a year, in the hope that a deep love for the mountains would take root in our pubescent minds.

It must have worked, because any time I see a book with “Himalayas” in the title, I start salivating. And if it has the etymologically correct singular “Himalaya” (from the Sanskrit hima-alaya, “abode of snow”), I pounce upon it instantly. So I relished the prospect of novelist Anuradha Roy’s first nonfiction work, which promised a journey beyond the merely geographical Himalayas, that thing of rock and snow, into the Himalaya, that realm of poetry, imagination and myth.

It met my expectations. From my polluted Delhi bedroom, I was whisked to Ranikhet, a hill town where the British set up a cantonment in 1869. Roy moved there 25 years ago, along with her husband, after falling in love with a rundown cottage.

Illustrated with Roy’s watercolours, this is a work of quiet beauty. Over 12 chapters, she shares numerous vignettes from her life in the hills: her arrival in the town; interactions with local characters; encounters with birds, dogs, snakes, scorpions; the threat of commerce and climate change.

Indeed, the writing shines so much that each time I encountered a quotation from another author, poet or scholar, no matter how relevant, I wanted to rush ahead to Roy’s own observations, which possess great wit and empathy. See, for example, her encounter with a mansplaining government official who keeps peppering his otherwise all-Hindi discourse with an English verbal tic: “sophar-sogud” (so far, so good).

At roughly 200 pages, it left me hungry for a lot more. At times, I wondered about such prosaic matters as: what’s the grocery supply like? How often do they go to the city? Any run-ins with quacks dispensing herbal remedies for every illness under the sun? I long for a follow-up that welcomes us more fully into Roy’s world. Until then: sophar-sogud.

Tanuj Kumar

The Shortest History of AI

by Toby Walsh (Old Street Press, £9.99)

Toby Walsh isn’t just a great demystifier of AI—he’s also a strident one. At the start of his new book, he says that he’s setting out to prove “there’s a lot less magic to AI than the media would have you believe”, adding that he aims to “cut through the lunacy, the wild claims, the myths and the threats”.

Given that Walsh is a prominent AI scientist, he’s in a position to deliver on these promises—although expertise doesn’t always translate into clear English. As it is, I certainly couldn’t begin to programme a neural network after reading this book, but I could go quite far in explaining how they work to my ever-suffering friends and family.

Its masterstroke is one of organisation. The Shortest History of AI is divided into two halves: “The Symbolic Era” (running roughly from the 1950s to the 2000s, when AI systems relied on logic equations and human input) to the “Learning Era” (when they started to teach themselves). Each of these halves then tackles three ideas that researchers have explored in that time, ending up with “You can compute the probability of an event, given evidence about the event, using Bayes’ theorem”.

If this sounds like a bloodless way of doing history, it is not. Walsh is a funny and considerate guide who lays out these ideas as a kind of path, something that readers can follow so they don’t get lost. Without such clear explanations of the actual science, the more tangible milestones—from chess computers to ChatGPT—would barely make any sense.

Besides, Walsh doesn’t leave out the people. The usual names appear—Alan Turing, Ada Lovelace, Geoffrey Hinton, Sam Altman—but I particularly appreciated the pen portraits of less heralded figures. One of the pioneers of neural networks, Walter Pitts, once devoured the 2,000 pages of Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell’s Principia Mathematica in three days, I learned, and then wrote to Russell about several mathematical errors he’d spotted. He was 12 years old.

The result is a book that’s both educational and enjoyable. Deposit it in school libraries—and on the reading piles of politicians, journalists and, indeed, anyone who hopes to understand the revolution.

Peter Hoskin

Murder at Mt Fuji

by Shizuko Natsuki, tr Robert B Rohmer (Penguin, £9.99)

Snow is falling when Jane Prescott, an American student, steps off the train in the foothills of Mount Fuji to join her friend Chiyo and her wealthy family for their annual New Year’s gathering. She’s there partly as a tutor and partly just as a pal, when, after a celebratory dinner, she becomes an unwitting witness to a murder. Chiyo stumbles down a hallway, clutching a knife, hollering that she’s killed her grandfather, the head of one of Japan’s biggest pharmaceutical companies.

Case closed? Of course not. After that arresting beginning, Jane—who, it must be said, remains unbelievably unflustered throughout, especially considering she’s an outsider to this setting—is drawn into the family’s web of lies. Just how far will they go to protect Chiyo, their own reputations and their inheritances?

Capitalising on the current boom in Japanese crime novels, Murder at Mt Fuji is republished by Penguin as a “rediscovered classic”. It wasn’t the first mystery penned by Shizuko Natsuki, who was hugely successful in Japan, but it was the first to be translated and published in English, in 1984, and is generally regarded as a good entry point to her wider body of work.

Natsuki draws the inevitable comparisons to Agatha Christie, and this story has practically all the hallmarks of the “cosy” murder mystery: a big house in the country, scandals buried for years, rumours of family curses and a sharp local detective with a keen eye for even the smallest detail.

Fans of Seichō Matsumoto and the intricate cases of Seishi Yokomizo’s Inspector Kindaichi will enjoy the twists and turns of this tale—but don’t expect a neat ending. The book doesn’t just ask a lot of Jane, it even expects the reader to question their own memory of events. Chilling, indeed.

Ellie Jay

White Moss

by Anna Nerkagi, tr Irina Sadovina (Pushkin Press £12.99)

In this novel—originally published in 1996 and translated now for the first time, ably, by Irina Sadovina—Anna Nerkagi draws an evocative portrait of her Nenets community, who live a nomadic existence deep in northern Siberia. At the heart of the story is Alyoshka, a young man who’s just got married, although the occasion feels more like a funeral than a wedding. He still yearns bitterly for his lost love, Ilne, the daughter of his old neighbour Petko, who left their camp seven years earlier, making a new life for herself in the city instead.

One has sympathy with the absent Ilne. Life on the tundra is harsh, and Nenets society is governed by traditional gendered roles in which women are subservient. “Don’t try to look further than your husband,” Alyoshka’s mother tells her new daughter-in-law. “Life is a long journey, and the path is always chosen by the man.” Yet even for the menfolk, theirs is not an existence in which they have much choice or personal freedom. The survival of the group is paramount. Alyoshka is the only member of the younger generation left: he needs a helpmeet, and children. Love has nothing to do with it. The needs of the community must come before his own happiness.

Replete with imagery that conjures up the unforgiving but beautiful natural world—a man is described as “living sturdily, solidly, sitting like a nail in this life: couldn’t be pulled out, couldn’t be broken,” while happiness is “like a fox: as soon as you see it, before you can reach for the gun, its tail has already flashed behind a nearby bush”—this is an almost fable-like story of rifts: between the young and the old, men and women, tradition and modernity.

Lucy Scholes