There has been a tectonic fragility to the early weeks of 2026, the uneasy sense of an old world shifting. New horror in Syria, Venezuela, Greenland, Iran; ongoing terror in Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan. In the United States, ICE raids and Department of Justice investigations; in the UK, political defections and rising migrant crossings. Amid all this, the potential end of Nato, the upheaval of AI, our warming planet’s point of no return.

Eight years ago, the Irish writer Fintan O’Toole introduced the idea of the Yeats Test as a way to gauge the geopolitical spirits. The premise is simple: “The more quotable Yeats seems to commentators and politicians, the worse things are,” he explained. I cannot have been alone in spending these first few weeks of January reflexively muttering that familiar line: “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold.”

In the wake of such geopolitical chaos, it always seems trite to write about the arts, and yet it is fascinating that in our cultural lives we can also see a disintegration. Our habits are now often described as “social yet separate”—watching and listening to different music, television, podcasts, while in the same room as our loved ones. Even alone, we are frequently “second screening”—scrolling our mobile devices while ostensibly watching TV.

In music, we can see this dissolution in an increasing stratification of genres. At the start of the year, the sample library Splice released the findings of a study into the trends and microtrends of musical taste likely to dominate the coming year. It told of the growth of house music—particularly the melodic form of Afro house, demand for which rose 778 per cent last year, amounting to 6.7m downloads. Other forms of dance music are flourishing, too—among them speed garage and hard techno. In hip-hop, there have been expansions into boom bap, rage and trap EDM. Pop, meanwhile, has enjoyed both a resurgence and a period of experimentation, with the growing popularity of hyperpop, bedroom pop and acoustic indie.

“We are at a turning point in music,” the study’s authors claim. “Taste has become so fragmented that mainstream culture is being replaced by highly diversified listening habits and the blurring of musical styles across genres and scenes.”

It’s natural to recoil from this kind of change. And it’s undeniable that the world’s recent re-orderings have been marked by something brutish and rapacious and dark. But culturally, and certainly in terms of music, I’m not convinced that fragmentation is necessarily cause for concern. Indeed, a greater anarchy now seems loosed through the centre’s desperate efforts to still hold.

As our musical tastes splinter, mainstream culture is engaging in desperate land-grabs to shore up the power of both major recording artists and major labels who might fear a not-so-hegemonic future.

Mainstream culture is engaging in desperate land-grabs to shore up its power

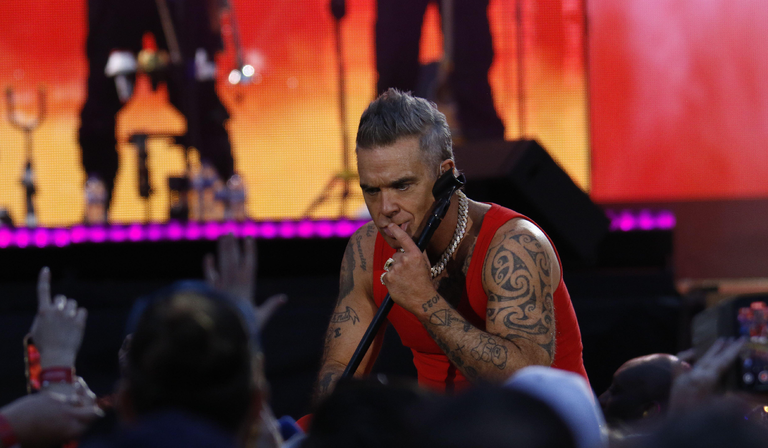

In the middle of January, Robbie Williams put out his 13th album, Britpop. It was originally announced last May and slated for release in October, before the prospect of going up against Taylor Swift’s The Life of a Showgirl gave Williams and his team the jitters. The album was pushed back to February.

The mid-January release, then, was something of a surprise. But we can see its early arrival as tactical: the singer’s record company, Columbia, laying a safe bet that Williams would knock Olivia Dean’s The Art of Loving off the top spot and encounter few other rivals in this quiet release week. The chart victory was crucial. Previously, Williams shared the title of “more number one albums” with the Beatles; Britpop, through a delicate conjuring of digital sales and preorders, pushes him out ahead.

As an album, Britpop is a curious thing. Williams himself has described it as a homage to “a golden age of British music”, and in the context of the original release schedule perhaps that might have made sense—the new songs swept up in the excitement of last year’s Oasis and Pulp live dates.

But in the light of this new year, the concept of the record feels disjointed. Williams, looking backwards to that giddy summer of 30 years ago when he quit Take That and started knocking about with the Gallaghers. Or further back still, in pursuit of a silly chart rivalry with the Beatles.

It speaks of an old world; of somewhere pale and male and stale. As 2026 sets out, I feel, increasingly, that the world I want to live in is a diversified blur; that the centre has held too long. Give me Afro house and bedroom pop, give me boom bap and rage, give me the sound of things falling apart.