When Italy failed to qualify for this year’s World Cup finals, it inevitably caused shock, dismay and a bout of national soul-searching. The fortunes of a football-obsessed society had been entrusted to a 69-year-old coach, Giampiero Ventura, whose greatest sporting achievement had been to clinch the third-tier Serie C1 championship 21 years earlier. Why had he been hired, asked Carlo Garganese on the website Goal? His answer, like that of many Italians, was “because of who he knew rather than because of his talent.” Ventura’s appointment exemplified the influence of what has been called “the veterans’ lobby.”

Their power is a function of Italy’s skewed demographics. Britain and the United States fret about being ageing societies, but next to Italy they look positively spritely. Where the median age is 38 in the US, and 40 in the UK, in Italy it is a touch over 44. And were it not for Italy’s immigrants the country would be greying even faster than it is. They are younger than native Italians, and women have a higher fertility rate, but they are not integrated enough to challenge the grip of Italy’s senior citizens. Few, indeed, have the vote. This means that 41 per cent of the voters called to the polls next month will be over the age of 55.

Men far older than Ventura continue to exert control in many areas of Italian society, infusing it with attitudes from a bygone era. In finance and industry, shareholder pacts allow firms to be controlled by investors with relatively modest holdings, and enable those same investors to retain influence almost indefinitely. Despite a reform some years ago that forced university teachers to retire at 70, academic staff are still getting older: the average age of professors is almost 60. Showbiz personalities—even pop singers—who built their careers way back in the 20th century remain among the biggest names in the charts.

If some Britons seem to be reliving a variant of the Second World War, then—to outsiders at least—it seems as if a large section of Italian society has its gaze fixed on the country’s dolce vita years, when the economy was booming, Italian design and fashion were all the rage, and Federico Fellini was wowing audiences in art-movie houses the world over.

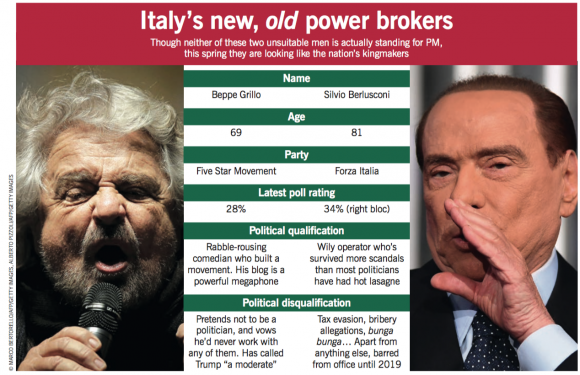

In politics, too, gerontocracy rules. There was a moment when its grip appeared to loosen. In 2014, Matteo Renzi was sworn in as Italy’s youngest ever prime minister, at just 39. The average age of his ministers was 47. Half were women. The break with the past, begun under his predecessor, Enrico Letta, looked irreversible. But Renzi’s hubristic decision to call a referendum on constitutional reform in 2016 proved fatal. When he lost and resigned, the “veterans’ lobby” simply returned. His genial successor, Paolo Gentiloni, also of the centre-left Democratic Party (PD), is 63. He is being challenged from the left by a party called Free and Equal, which is headed by a 73-year old former anti-mafia prosecutor. And to the disbelief of many outside Italy, the likely kingmaker in the coalition talks that are expected to follow the ballot is the 81-year-old disgraced former prime minister, Silvio Berlusconi.

Then there is the Five Star Movement (M5S), which, was leading the polls when the election was called. At first blush, this looks like a reaction to Italy’s aged political guard: it’s only been in existence for nine years, and has great appeal to the young. But the real power in the Movement is wielded by Beppe Grillo, the 69-year-old semi-retired comedian who founded it. Grillo got his first big break in television in 1977, when Jim Callaghan was prime minister in Britain and the BBC was still cheerfully broadcasting The Black and White Minstrel Show. In Italian politics, even the new is led by the old.

*** At Italy’s last general election in 2013, a quarter of the electorate voted for the M5S. It has been the key to understanding Italian politics since then. Outside the country, though, it is widely misunderstood—lumped together with the other populist parties that have made big inroads across Europe by posing as “anti-establishment.” Often, that is just a pose, but in the M5S’s case the label is apt. What has made it a peculiarly disruptive force is that until now, it has refused even to discuss forming electoral alliances or governmental coalitions with other parties. In fact, it does not consider itself a party at all: so far at least, its animating mission has been to do away with Italy’s discredited old parties and the whole system of traditional parliamentary democracy in which they have always worked. What the M5S claims to want to put in its place is an internet-based form of direct democracy.

The Movement’s outright refusal to work with others marks it out from non-populist reformers, such as Britain’s Liberal Democrats, who may want to abolish the electoral system or the House of Lords, but see the route to doing so as playing by the established rules. The M5S’s refusenik approach also distinguishes it from many populist forces. However radical and different their ideas, Podemos in Spain and the Alternative für Deutschland—even Italy’s own Northern League-—all seek to work inside an existing system to bring about change. The M5S openly campaigns to replace that very system.

The man who inspired Grillo to create his movement was the late Gianroberto Casaleggio. An internet executive and would-be visionary, Casaleggio’s point of departure was the remorseless destruction by the internet of all forms of intermediation. Just as estate agents, second-hand car dealers and—he was convinced—newspapers and magazines were all doomed to extinction, the same would prove true of political parties. In future, voters would not be content to hand power over to parties and politicians they chose every few years. They would want to say “yes” or “no” to policies and bills in the way they already bought goods directly from Amazon and liked or unliked videos on YouTube. Democracy would thus return to its classical, Athenian roots--—except that decisions would be taken, not with a show of hands on the Pnyx, but over the internet.

While the M5S’s policies reflect a mix of left- and right-wing ideas that put the party, on balance, close to the middle of the traditional spectrum, Casaleggio’s ultimate goal was revolution. And, as he once remarked to his friend and associate, “You, dear Beppe, will play the role of Robespierre.”

The M5S’s role was to facilitate the change. And, to some extent, anticipate it: its representatives regard themselves as “spokespeople” for policies decided by the membership in online polls. It may sound gloriously representative, but it is striking how often what emerges from this supposedly unco-ordinated process bears a close relation to Grillo’s own proposals. He has steered the Movement towards a more Eurosceptic line, for example, and a tougher stance on immigration.

How long the M5S will be willing to sit on the sidelines remains to be seen. In March, the electorate may offer it a chance to participate in government. The lure of power is great, and the Movement has already taken on some attributes of the parties it so despises. Two years ago, it won control of the city halls of Rome and Turin, yet in neither city has the M5S mayor done much to introduce the citizenry to the joys of direct democracy. Some of the political novices elected to parliament five years ago have become considerably more than “spokespeople.” The most notable example is Luigi Di Maio, a 31-year-old from near Naples who is the Movement’s candidate for prime minister. Berlusconi once scathingly remarked that Di Maio’s only proper job before that of lawmaker was as a steward at Napoli’s home football matches.

In December, Di Maio appeared to change M5S’s attitude towards power when he told an interviewer that, if the Movement fell short of the 40 per cent of votes needed for an outright majority in parliament, it would be ready to accept the support of any party that agreed with its programme. How far things have really shifted is less clear. Being willing to accept external support is very different from negotiating a coalition deal. More dangerously still, hard decisions and compromises could shatter the all-things-to-all-men ambiguity that has got the Movement this far.

But by so far sticking to its policy of non-co-operation, M5S has created a giant headache for Italy’s mainstream politicians. The Movement’s substantial representation in parliament has meant that neither the left nor right could form a viable government; it is no exaggeration to say that its success has blocked the normal functioning of democracy. Some form of “grand coalition” was left as the only way forward.

Each of the three governments since the M5S breakthrough in 2013 has been an inherently unnatural grouping of people with contrasting ideas. First came Enrico Letta’s cabinet, which included, among others, representatives from the PD and Berlusconi’s Forza Italia. After Berlusconi tried withdrawing his party’s support, Forza Italia’s representatives in cabinet and some other members broke away to form the New Centre Right (NCD). The NCD went on to prop up Letta, Renzi and latterly Gentiloni in turn. The price the PD had to pay was a veto over any legislation that might upset the NCD’s tiny, conservative electoral base, most recently and notably a bill to give automatic citizenship to the children of immigrants.

That any of these right-left coalitions managed to reform anything is a tribute to the Italian talent for negotiating compromises. But the sight of politicians who deplore and ridicule one another on the hustings sitting together around a cabinet table only helps Grillo: it lends credibility to his argument that all the power-hungry parties are fundamentally the same.

The polls are pointing to another hung parliament. After Renzi’s attempt to clip the wings of the Senate and decisively reform Italy’s electoral laws so spectacularly went awry, the procedural sclerosis which gave rise to M5S in the first place seems likely to intensify. The shape of the government will probably need to be decided afterwards in tortuous negotiations. Bizarrely, many older Italians find that prospect rather comforting. It is the way things worked through those dolce vita years: governments were led by the Christian Democrat and alliances with other parties ensured that the Communists never got into power. This would be essentially the same, but with the M5S taking the place of the old Communist Party as Italy’s political leper.

The Cold War era saw parties making numerous compromises and bargains, many of them immoral. But notwithstanding dizzyingly frequent changes of government, there was an underlying stability that allowed the economy to prosper and generate that golden era of Italian growth.

The danger today is that nostalgia for these times obscures the reality: the world is a different place today. One reason why Italy has stagnated so lamentably since the turn of the century is that it has not benefited from the sort of bold- and often unpopular reforms that a modern economy needs. These can only be imposed by a government with clear priorities and a secure majority. Between 2001 and 2006, Berlusconi had just such an unassailable majority, but his priorities were notoriously self-serving.

Another reason for Italy’s economic sluggishness is the euro. The old way out of economic discipline was to devalue the currency; this was a route post-war Italy often took, and though there was a price to pay in the ludicrously low purchasing power of the lira, it allowed the economy to keep growing without Italians having to face up to divisive questions about what standard of living the country could afford. Inside the single currency, that escape route no longer exists. Small wonder Euroscepticism has grown and that, while shrinking from a commitment to abandon the euro, the M5S, the Northern League and Forza Italia have all tried to cash in. The favoured wheeze is to argue for a parallel currency.

Even against this litany of political and economic problems, many outsiders will be scratching their heads at how on earth it can be that the repeatedly humiliated Berlusconi is back as a serious force. How is it that a country in obvious need of a serious overhaul could, once again, be in thrall to an octogenarian with a criminal record?

It is the prospect of two different scenarios that has once again made him a player. First, if yet another “grand coalition” has to be formed, the obvious partnership is between the centre-left PD and Berlusconi’s Forza Italia. Second, if the electoral arithmetic were to enable a minority right-wing alliance—as it might—Berlusconi’s party would probably dominate. Forza Italia has been gaining support since last spring, and entered the campaign a nose ahead of the Northern League. Some of this has to do with the emergence of a supposedly new Berlusconi. Gone is the priapic host of the notorious bunga bunga parties, his place taken by a grandfatherly figure, albeit with a 32-year-old partner, who has converted him to animal defence and vegetarianism. Who says men in their 80s can’t change?

Then, on top of all the spin and electoral arithmetic, there is the Trump factor. Italy’s former prime minister is often seen as the US president’s precursor, and rightly. Both men made their fortunes in real estate and used television as a platform from which to launch themselves into politics. Both can be toe-curlingly vulgar; campaigning in the Sicilian regional elections last year, Berlusconi told his audience a joke that combined African immigrants, bidets and fellatio. He and Trump also share a distinctly shaky relationship with verifiable fact. And yet the comparison with America’s chaotic and scattergun president actually works well for Berlusconi—whatever else he may lack, governmental experience is not among them. My predecessor as Economist correspondent, Beppe Severgnini, wrote that, compared to the US president, Berlusconi “looks like Winston Churchill.”

Implausible as it may seem, given his endless legal difficulties, a conviction for tax fraud and disqualification from public office, Berlusconi’s role in the election will be to reassure. He may not be Italy’s next PM—the European Court of Human Rights is unlikely to rule on his appeal against disqualification before voters go to the polls. But that doesn’t mean he can’t campaign, and his new, softer image will bolster the spin that he and his allies belong to the centro destra, the respectable centre-right.

The reality is different. His partners are the hard-right, anti-immigrant Northern League, and a smaller and even more radical party called the Brothers of Italy (ironically led by a woman). There was much controversy about the company Berlusconi kept when he first entered politics in 1994, in a reactionary coalition that included the League (then more moderate than now) and Italy’s old neo-fascist party, unconvincingly rebranded as the National Alliance (AN). Since then, AN has been simply dissolved into Forza Italia, with the exception of the diehards who stalked off to form the Brothers of Italy. Any government to emerge from this mix could be every bit as strident, and perhaps more so, than that singularly controversial administration all those years ago.

But Berlusconi styles his supporters and allies I moderati (the moderates). And his electoral pledges include measures many middle-of-the-road conservative leaders might toy with: a new minimum pension of €1,000 a month and—reflecting the new, cuddly Berlusconi—scrapping VAT on dog food. At the same time, however, he has proposed a flat rate of income tax and floated the idea of making a retired general from the Carabinieri (Italy’s fourth military force, which also discharges policing duties) as the right’s candidate for prime minister.

Of course, it is also quite conceivable that no government at all can be formed. Italy would then follow Belgium, Spain, the Netherlands and Germany into a period of caretaker rule. Italians have often known political crises, and seem unfazed by the prospect. Financial analysts are less sanguine. They fret that prolonged uncertainty might set off jitters among bond dealers and inflate the cost of paying for Italy’s huge public debt (over 130 per cent of GDP), just as it did when the euro crisis set in back in 2011.

There is one final possibility. The new arrangements do not tie parties to their electoral alliances when it comes to forming a government. So, in theory, the populists in the League could join forces with the populists of the M5S. Representatives of both have pooh-poohed the idea. But if anything has characterised the M5S in recent months, it is a gradual shift to more conservative positions that has strained the loyalty of some of its activists. Among other things, the Movement has opposed a move to tighten up a largely ineffective law restricting the use of fascist-era symbols and propaganda.

An M5S/Northern League coalition would certainly represent a setback for the “veterans’ lobby.” The League’s leader, Matteo Salvini, is only 44 and many of the M5S’s prospective ministers are in their thirties. But it could also turn out to be a lot more frightening than a bout of political paralysis. Which is why such a discredited character as Berlusconi can pose convincingly as a guarantor of stability.