The enormous gamble that Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu has taken with his citizens’ lives seemed to have paid off when the United States this weekend joined Israel’s military operation against Iran. Early on Sunday morning, US B-2 bombers struck three nuclear sites at Fordow, Natanz and Isfahan with 14 mass ordnance penetrators (otherwise known as “bunker buster” bombs) as well as Tomahawk missiles launched from a submarine.

It had been clear since Israel first attacked Iran’s nuclear programme on 13th June that Netanyahu was counting on President Trump striking these facilities, which are built deep underground, and which only American weapons can reach. He argued that their destruction was critical to Israel’s war aims and that Israel’s ability to end this operation depended on American involvement.

Iran retaliated by striking a US military base in Qatar, warning the Americans ahead of time and avoiding any casualties. It seemed Tehran had given Trump an off-ramp, and some hours later Trump announced a “Complete and Total CEASEFIRE”, starting “in approximately six hours from now when Israel and Iran have wound down and completed their in progress, final missions!”. This may not last: an hour or so after Israel’s government officially acknowledged a ceasefire on Tuesday morning, a missile barrage was intercepted in the north of the country. Israel vowed retaliation “against regime targets in the heart of Tehran”, while Iran denied firing further missiles after the ceasefire came into effect.

Whatever happens next, two things are clear: military action is unlikely to stop Iran’s nuclear programme, which has been some 25 years in the making—and Netanyahu seems to have secured his political future once more.

It still isn’t clear how much damage was done by the US strikes. On Monday, the head of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) said that “very significant damage is expected to have occurred”, but that “at this time, no one, including the IAEA, is in a position to have fully assessed the underground damage at Fordow”. It was reported, meanwhile, that the Iranians may have moved weapons-grade enriched uranium from Fordow to a hidden location ahead of the US attack.

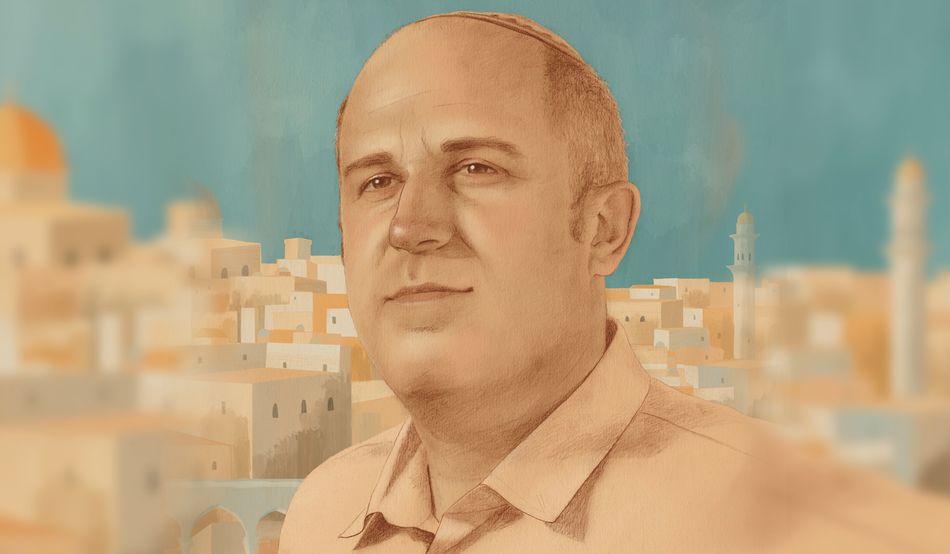

Whatever the damage caused by the US bombs, “the bottom line is you can't destroy this programme militarily”, Danny Citrinowicz, formerly head of Iran research and analysis in Israel’s Military Intelligence Directorate, says. No matter how much Israel may have managed to degrade Iran’s nuclear facilities, no matter how many nuclear scientists it has killed, Iran has the knowledge and capability to rebuild its programme. And Israel's apparent approach of treating Iran like one of its proxy groups, assassinating military commander after military commander, won’t work against a nation state.

The fact of the US involvement will reverberate for decades, as it contained “many firsts”. It occurred seemingly under pressure from Netanyahu, without the US being attacked, without congressional approval, and based on Israeli intelligence which US counterparts weren’t convinced by. “It’s not just another thing. It’s history, for better or worse,” say Eran Etzion, a diplomat and strategist who served as the former deputy head of the National Security Council in Israel’s Prime Minister’s Office.

Israel began this war without an exit strategy, save for the general understanding that the US would take part. At first it hit nuclear targets but soon Israel was striking non-nuclear targets, such as, on the 23rd June, a prison—a sign that it was trying to topple the Iranian regime.

Watching Israeli news channels since 13th June, the hubris over the “historic” operation has been palpable. Netanyahu describes the war as “existential”. The word Israelis have been using to describe the mood regarding the attack on Iran is “euphoria”.

No one was more euphoric than Netanyahu himself. The Israeli leader has for decades obsessed about the Iranian threat, and has thwarted diplomatic solutions to Iran’s nuclear programme. For instance, over his political career Netanyahu has reversed the previous Israeli policy of letting “the major powers deal with Iran, because it’s a global problem and not an Israeli problem”, explains Etzion. He fought the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action—also known as the Iran nuclear deal—and warned the United States against making “a very bad deal”. He then pushed Trump to leave the agreement in 2018, and in the recent rounds of negotiations with Iran he argued for limits on Iran’s nuclear programme that were “tantamount to [Iran’s] surrender”, Etzion adds. “It [was] an elegant (or inelegant way) to blow up the negotiations.”

For now, Netanyahu’s enormous gamble with countless lives in the region has paid off for him politically. His Likud party is polling higher than others (and three points ahead of its nearest rival). Eighty per cent of Israeli Jews support the war against Iran, despite Israelis having spent days on end under fire, with 28 people killed and entire neighbourhoods destroyed by Iran’s missiles. On 24th June, Human Rights Activists in Iran, an organisation tracking the conflict, said the death toll in the country was at least 974.

Only a day before the Iran strikes, on 12th June, opposition parties had voted to dissolve the Knesset parliament over a bill to end exemption from the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) draft for ultra-Orthodox Jews (though this ultimately didn’t pass). But on 16th June, a no confidence motion against the government failed. Netanyahu’s major political rivals—people who were key in building political momentum against him, such as Yair Lapid, the current leader of the opposition, and Naftali Bennett, his main rival for prime minister in Israel’s next election—have been working hard to show just how much they support the war, on social media and through foreign media interviews.

Netanyahu is Israel’s longest-serving prime minister. He has expertly outwitted political rivals and has gone to great lengths to stay in power, including forming a coalition in December 2022 with parties of the far right. Since May 2020, he has also been on trial on corruption charges.

In the nearly two years since the horrors of 7th October, a national tragedy for which Netanyahu has yet to take any responsibility, Israel’s prime minister has led a traumatised nation through continuous war on multiple fronts. He has scuppered ceasefire efforts in Gaza, abandoned hostages held by Hamas, and enabled his extremist coalition partners who want to annex Palestinian territories in the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza.

At a press conference on 21st June, when asked if he would leave politics after completing what appears to be his life’s mission against Iran, he said that he had “many more missions”, but that ultimately only “the people” would decide.

Europe’s leaders seem to have tacitly welcomed Netanyahu’s enormous gamble, taken with no guarantee that it could work to bring long-term stability to the region let alone peace, or an agreed causus belli. Before 13th June, the UK announced sanctions on Israeli ministers and France was considering recognising a Palestinian state. Even Germany had, unusually, expressed criticism of Israel’s continued atrocities in Gaza. But efforts to up the pressure on Israel seem to have dropped as a priority, in favour of appeals to Iran to return to negotiations. Germany’s chancellor, Friedrich Merz, said the quiet part out loud when he told German media on 19th June that Israel was doing “the dirty work…for all of us”.

A long-lasting agreement between Israel and Iran will be complex, because every side has a “different interest”, Citrinowicz says. “Without an agreement we will always attack them, and they will attack us… It won’t end.” If the US wants to stop the war with an agreement, and Israel wants to topple the regime, “Iran, I think, wants a war of attrition with Israel at the very least,” says Citrinowicz. “I don’t know how you can bridge these gaps.”