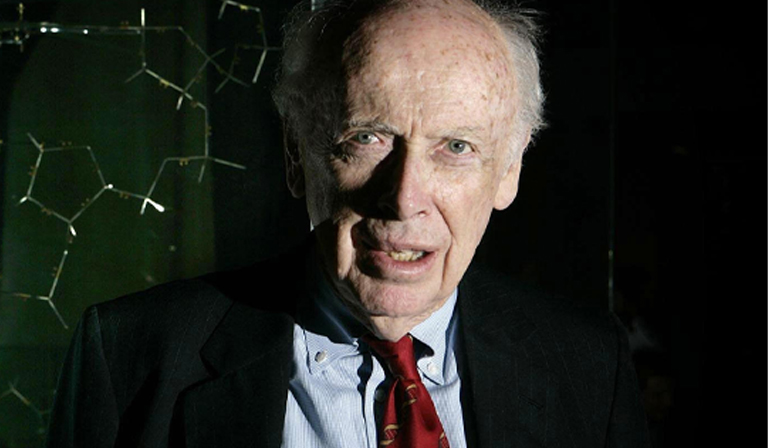

When James Watson died on 6th November last year at the age of 97, he was survived by a wife, two sons and a severely tarnished reputation. Watson was one of the world’s most famous scientists, having been awarded the Nobel for the co-discovery of the structure of DNA in 1962. His subsequent book The Double Helix (1968) was one of the most influential nonfiction titles of the 20th century. In 1988, he became the director of the Human Genome Project, an ambitious attempt to decipher the complete set of human genetic material. Watson famously left the project in 1992, having failed to stop some colleagues from patenting the genome. “The human genome belongs to the world’s people, as opposed to its nations,” he said.

A long life affords a person plenty of opportunity to fall off their pedestal. As his impressive career advanced, Watson became notorious for expressing avowedly racist beliefs about human ability and biology. He was also known for his sexism; the story of Rosalind Franklin, the colleague whose contributions to the DNA discovery were overlooked, and whom Watson publicly belittled and demeaned, may be familiar. As such, his career presents a paradox: Watson was celebrated as one of the leading scientific minds of our time, but some of the things he said were regressive and bigoted. In a word, they were unscientific.

Born in Chicago in 1928, Watson was a precocious student, going to university at 15 to study ornithology. In the spring of 1946, his plans changed when he read the physicist Erwin Schrödinger’s book What is Life? Schrödinger, who is now known to have been a sexual abuser, was an undeniable influence. His book asked: what is the gene? That is, what is the biological mechanism of heredity? How are traits passed from one generation to the next? “That,” Watson said, “was a really big idea.”

In her 2021 book Narrative in the Age of the Genome, the academic Lara Choksey traces the biography of the gene from a proposed unit of heredity in 1900, to being located in the chromosomes the following decade, to being a blueprint for protein molecules in the 1940s. One notion has remained remarkably resilient throughout: that the thing that makes us us is somehow encoded in our bodies.

Watson picked up this idea and, in 1951, his search for the gene landed him at Cambridge University where he met Francis Crick, with whom he would later win the Nobel. Watson became part of a research community attempting to crack the molecular structure of DNA—a substance present in cells that had recently been proven to be the active component of heredity. In The Double Helix, Watson told the story of the discovery, casting himself in the role of incendiary genius and everyone else as directionless, stupid or both.

According to Watson and Crick’s biographers, the search for the double helix was much more collaborative. Working at King’s College, London, Franklin, Raymond Gosling and Maurice Wilkins provided crucial experimental data. Then at Cambridge, Crick and Watson used that data to test different molecular models until they finally hit upon one that worked. In Watson’s eyes, it was so beautiful that it had to be true.

In 1962, when Crick, Watson and Wilkins won the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine, it cemented Watson’s reputation. He worked at Harvard for a few years before settling down at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York state. Over the decades, his colleagues often despaired at the things he said. According to EO Wilson, the noted biologist who was posthumously revealed to share some of Watson’s views on race and intelligence, “his bad manners were tolerated because of the greatness of the discovery he had made.”

Watson’s wasn’t a casual prejudice. In October 2007, the Sunday Times quoted him as being “inherently gloomy about the prospect of Africa”, because “all our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours—whereas all the testing says not really.” Despite resigning his chancellorship of Cold Spring Harbor as a result of the scandal over his views, years later Watson doubled down on those comments. Asked if his views had changed, he replied: “No, not at all.” He did regret hurting people, he said, but in the absence of any new evidence he had to stick to the view that differences in intelligence were genetic. “It should be no surprise,” he said, “that someone who wanted to find the double helix believed that genes were important.”

‘It should be no surprise,’ Watson once said, ‘that someone who wanted to find the double helix believed that genes were important’

Through the success of The Double Helix, Watson had popularised the idea that everything you need to know about a person is encoded in their body. He was building on old foundations. The same thinking that ran through 17th-century race science and 19th-century eugenics now informed 20th-century ideas about genetics.

Like traits, ideas have their antecedents, and they can also be handed down. Watson’s generation of scientists inherited the idea that moral and character traits can be passed on like physical ones. It’s an idea that informs the 1994 book The Bell Curve by Richard J Herrnstein and Charles Murray, which Watson’s biographer Nathaniel Comfort describes him as “brandishing” while walking around the Cold Spring Harbor campus. The book is notorious for its controversial findings that black people are inherently less intelligent than other racialised groups.

Watson’s scientific collaborator Crick had taken up eugenics himself. In a 1971 letter to a colleague at the Fogarty International Centre (for medical research), Crick wrote, “I think it likely that more than half the difference between the average IQ of American whites and Negroes is due to genetic reasons, and will not be eliminated by any foreseeable change in the environment.” And in another letter from the same year: “The Nazis gave [eugenics] a bad name and I think it is time something was done to make it respectable again.”

Such thinking was there in plain sight, if you knew what to look for. Echoing the earliest eugenicists, Watson invoked his best-known, if distant, relative: “I like to believe that I’ve been successful for some of the genes that I probably shared with my relative Orson Welles.” Just as Citizen Kane was the best movie ever made, so the discovery of the structure of DNA was “the greatest bit of chemistry ever done”. (Watson’s own account is that Welles was a Watson on his mother’s side. It seems that he didn’t engage much with his cousin’s work beyond its reputation, or else the film’s central theme of success resulting from inherited wealth and privilege might have rubbed off on him.)

Given Watson’s beliefs, the Human Genome Project is arguably the greatest failed experiment in the history of science. It had been hoped that mapping and sequencing the genome would lay bare the secret to life. What the first eugenicists had tried to do at the macro level—measuring heads, limbs and ability—this global collaboration attempted at the molecular level. The result was both unexpected and edifying.

For all that your genome can tell you about yourself, there’s a lot that it can’t. It can place you at the scene of a crime or determine if the person you think is your parent is in fact your parent. It can help to map where the people whose genes are most similar to yours are distributed geographically. It can indicate if you have, or are likely to have, certain diseases. It can’t tell you how clever you are, nor how likely you are to be successful.

The irony is that the Human Genome Project ultimately put paid to the notion of race. The false divisions put in place by race scientists and eugenicists failed to hold. At the molecular level, we are all very tediously alike. There lies the inherent contradiction of James Watson: the brilliant mind unable to see past the limitations of bad science.