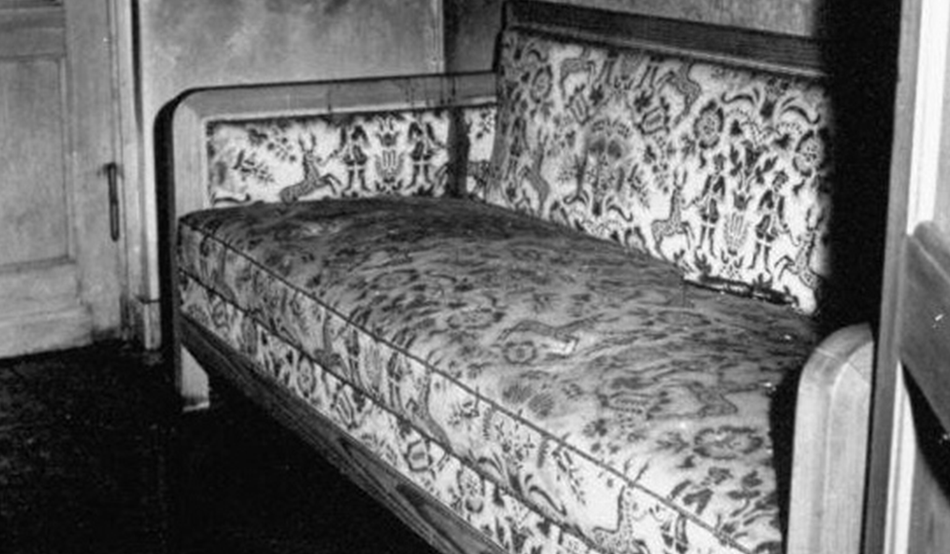

Few historical figures have been discussed and debated as much as Adolf Hitler. We have a wealth of primary source material available to us about his life, including his autobiographical manifesto Mein Kampf, personal correspondence, political directives and military orders, recordings and transcriptions of his countless speeches, eyewitness accounts, photographs and film footage. Now, 80 years after his death, a groundbreaking documentary has unlocked a new source by presenting the results of a world-first analysis of a sample of Hitler’s DNA. The sample was taken from the blood on a small piece of fabric cut from the sofa on which Hitler bled to death after shooting himself in his Berlin bunker on the afternoon of 30th April 1945. Eight years in the making, Hitler’s DNA: Blueprint of a Dictator was produced by Blink Films and is currently airing on Channel 4.

For the very first time, Hitler’s DNA has been identified. Painstaking scientific testing carried out for the documentary confirmed that the DNA in the blood sample belonged to the 20th century’s most notorious figure. This was achieved by successfully matching it with the DNA of a male-line blood relative. Hitler now joins other famous historical figures, including Ludwig van Beethoven, whose genomes have been sequenced. I had the privilege of being part of this documentary as senior historical consultant and lead investigator, together with the geneticist Professor Turi King, best known for leading the DNA verification during the exhumation and reburial of King Richard III.

Let us be clear about what Hitler’s DNA can tell us and what it cannot. No attempt to explain the man he became and the extreme inhumanity he exhibited can be reduced to a question of genetics. Environmental and social factors played a central role. Born in provincial Austria in 1889, he had a very traumatic childhood, experiencing abuse at the hands of his father and losing four out of five siblings as well as both parents by the time he turned 19 years of age. He later wrote in Mein Kampf that his mother’s death had been “a dreadful blow”. Experiencing such loss during one’s formative years would have a lasting effect on anyone. These events were arguably at least as significant in shaping him as his genes were.

Similarly important for the bigger picture is the fact that Hitler was only one man. He was the undisputed dictator of Germany for 12 years. He devised and ordered the genocide of Europe’s Jews, as well as countless other atrocities. But he did not act alone. There were hundreds of thousands of German and Austrian perpetrators. Millions more eagerly followed him and profited from his policies. Genetics does not bring us any closer to understanding and explaining how the Holocaust could have happened.

At the same time, it is undeniable that certain people have a huge and lasting impact on the course of historical events. Hitler is one of those people. The historian Ian Kershaw, author of the definitive biography of the Nazi leader (and one of my own academic mentors from my time at the University of Sheffield), once wrote of the dictator: “He is one of the few individuals of whom it can be said with absolute certainty: without him, the course of history would have been different.” Being able to decode Hitler’s DNA thus offers us a remarkable and singular opportunity to learn more about the inner workings of the man regarded as “the embodiment of modern political evil” (Kershaw, again).

The DNA analysis has produced two major discoveries

In addition to the significant finding that the blood sample in question did indeed belong to Hitler, the DNA analysis has produced two major discoveries. The first concerns the question of whether Hitler had Jewish heritage through his paternal grandfather. In view of Hitler’s virulent antisemitism and his pivotal role in the extermination of almost six million European Jews, it is understandable that this particular rumour has triggered a great deal of speculation among both scholars and the general public alike. It is important, therefore, that the rigorous scientific testing carried out for the documentary has now confirmed beyond doubt what serious historians had long believed, namely that there is no truth in the rumour that has circulated since the early 1920s. The documentary firmly debunks the Jewish ancestry myth.

Of far greater interest to me as a historian, however, is the second major discovery: that Hitler had Kallmann syndrome. Among other things, this genetic disorder can result in an impaired testosterone production, low libido, underdeveloped reproductive features and, by extension, a disrupted reproductive function. The revelation that Hitler had Kallmann syndrome is intriguing because of the likely implications for his private life. This finding strongly suggests a causal relationship between Hitler’s genetic make-up and particular facets of his behaviour. It complements what we already knew about this part of Hitler’s biography and it sheds light on aspects of his life that we could previously only speculate about. For example, it might explain why Hitler’s personal physician, Dr Theo Morell, was injecting him with the male sex hormone testosterone during the final years of his life.

As we have known since the medical file resurfaced at an auction in 2010, a physical examination during Hitler’s time in Landsberg prison in 1923, following the failed Munich putsch the previous November, revealed that he had “right-sided cryptorchidism”—that is, an undescended testicle. (It turns out that the British satirical song “Hitler Has Only Got One Ball”, the origins of which remain unknown, was right, after all.) This physical abnormality might help to explain the account given by Hitler’s closest (and perhaps only) friend during his adolescence, August Kubizek, our most important source for this period. While living in Vienna, Hitler and Kubizek shared a room from February to July 1908. Noting Hitler’s “obvious indifference to the opposite sex”, his “strict monk-like asceticism” and the fact that he “refrained from masturbation”, Kubizek observed: “my friend undoubtedly found favour with the opposite sex although, to my amazement, he never took advantage of it”. Commenting on the entirety of their friendship from the autumn of 1905 (not 1904, as Kubizek claimed), when they met at the opera in Linz, to the summer of 1908, when their time together in Vienna came to an end, Kubizek concluded: “I think I can say with certainty: Adolf never met a girl, either in Linz or Vienna, who actually gave herself to him.”

Tellingly, one of Hitler’s closest confidants during the 1920s and 1930s, Ernst Hanfstaengl, later wrote:

“I can never recall having seen him in a bathing costume, nor had anyone else. A story, probably authentic, was frequently told that Hitler’s old army comrades, who had seen him in the wash-house, had noted that his genital organs were almost freakishly underdeveloped, and he doubtless had some sense of shame about displaying himself. It seemed to me that this must all be part of the underlying complex in his physical relations, which was compensated for by the terrifying urge for domination expressed in the field of politics.”

According to Ian Kershaw: “Kubizek’s account, together with the language Hitler himself used in Mein Kampf, does point at the least to an acutely disturbed and repressed sexual development.” Rumours that Hitler had been infected with syphilis by a Jewish prostitute were without foundation. Medical tests in 1940 showed that Hitler had not suffered from syphilis. The discovery that Hitler had Kallmann syndrome might thus be the key to explaining his seemingly “disturbed and repressed sexual development”. As Hanfstaengl observed, Hitler must have been extremely self-conscious about his body and, for this reason, reluctant to engage in relations of an intimate or sexual nature—and perhaps even uninterested in that side of life. This fact would help to explain Hitler’s absolute devotion to politics to the almost complete exclusion of any kind of private life. Such devotion was exceptional among Nazi leaders. All other senior Nazis—Hermann Göring, Heinrich Himmler, Joseph Goebbels, Martin Bormann, Rudolf Hess, Albert Speer, and so on—had wives and children; some even had extramarital affairs.

Ian Kershaw once wrote:

“There was no ‘private life’ for Hitler. Of course, he could enjoy his escapist films, his daily walk to the Tea-House at the Berghof, his time in his alpine idyll far from government ministries in Berlin. But these were empty routines. There was no retreat to a sphere outside the political, to a deeper existence which conditioned his public reflexes.”

Thanks to the discovery and testing of Hitler’s DNA, in combination with the historical facts already available to us, we now understand why.

I have long thought that only under Hitler could the Nazi movement have come to power, consolidated that power, waged a European war and committed the most terrible crimes in modern history. One reason for this is Hitler’s single-mindedness in the pursuit of power, which was unmatched by any other senior Nazi. Hitler’s genetic makeup contributed to this devotion. The fact that he had Kallmann syndrome surely played a part in his renunciation of any kind of private life or intimate relationships. All available evidence suggests that he did not even have sex with his long-term companion, Eva Braun. Hitler always claimed that his life was devoted to Germany, so that there was no room in it for a wife. It seems this claim might, at least in part, have been a way of covering up his aversion to intimate relationships, and that his genes may have played a bigger part in his decision not to marry and have children than he was willing to admit.

No single piece of evidence explains everything. We cannot view the genetic information about Hitler in isolation. It must be seen in the context of what we already know from historical sources about him and the era in which he lived. However, the discovery of this DNA and the findings that have emerged from its analysis and which are now presented in this cutting-edge documentary provide historians with a unique and extremely significant new piece of the jigsaw puzzle in their attempts to understand and explain Adolf Hitler.