I recently took a DNA test at the instigation of my sister-in-law, who has an interest in family trees and ancestry more generally. It came back as “100 per cent North Wales”. This did not surprise me. My mother came from a small village near Harlech, my father from a rural community near the town of Machynlleth, inland from Aberystwyth. They left in the 1930s, separately, to find a new life in the East End of London, my mother as a primary school teacher, my father as a bank clerk. In those days there was a thriving Welsh community in the capital, including Welsh-language Calvinistic Methodist chapels in the East End and on the Charing Cross Road, and after Sunday services the people would gather at a spot in Hyde Park known as Welsh Corner. There my parents met and, in 1940, they married. I was born in 1947, a typical postwar baby-boomer.

Every year at Easter—and sometimes in the summer too—we would go to Wales on the Cambrian Coast Express to visit family, an experience I always enjoyed. But Machynlleth and the surrounding area were experiencing a sharp decline in fortunes. The basis for the economy, the slate industry which had employed my grandfather, was collapsing. The narrow-gauge railway which ran from Corris to Machynlleth along the Dulas valley, below the farm where my father had grown up, ceased operating in 1948, the track torn up and the permanent way soon overgrown by bushes and brambles. The small hill-farms dotted around the area had depended on the income brought in from the men who worked in the quarries, and one by one they were deserted and fell into disrepair. For a time, they served as a refuge: for people seeking an alternative lifestyle or the remoteness necessary for setting up a cannabis farm or some similar operation, away from the prying eyes of the law. During one visit, my father, walking up the main street in Machynlleth, fell into conversation with a wild-looking, long-haired “hippy” (his description) who told him he played in a rock band. “Which one?” my father asked. “It’s called Led Zeppelin,” the man told him. It was Robert Plant.

My unmarried aunt Jane lived in the old family hill-farm halfway up the Dulas valley, close to the village of Pantperthog and a mile or so from the disused Llwyngwern quarry, which was repurposed as the Centre for Alternative Technology in the 1970s. I used to love visiting her and going for long walks in the surrounding hills. “Some new people have moved into Gellygen Fach,” she told me when I was staying with her in the early 1970s: “You should go and say hello to them.” This was welcome news: the grumpy Welsh couple who used to live there were unfriendly and had shot my aunt’s sheepdog, Wally, when he had escaped and run the mile or so up the hillside and onto their property.

One summer’s evening I walked along the lane with my then girlfriend, who was doing a degree in psychology, and turned left towards the old farm at a fork in the road. Most of the land had been sold to the Forestry Commission, and Gellygen Fach was now surrounded by conifers. As we came out into the open, a strange sight greeted us. On a small west-facing slope to the right, which had been kept as a lawn, two figures were bending over, close to the ground. Hearing us coming, they stood up to greet us. Each of them was wielding a large pair of scissors, which they were using to cut slugs in half. The sickly yellow light cast onto the lawn by the setting sun, and the rancid yellow slime oozing from the bodies of the butchered slugs, made an indelibly sinister impression.

The couple took us into the house, which had been renovated and modernised. Set into the top of the gable-end there was a slate panel on which was carved the inscription: “Wanda Chantler, artist. Alan Chantler, ornithologist”. They showed us round. I remember being particularly impressed by the sunken bath, set into the tiled floor of the bathroom. Over tea and biscuits, we conversed about our lives. They had met in a German prison camp, they said. Born in 1923, Wanda was “White Russian” (in fact, she was Polish, born Wanda Cieniewska). She was a prisoner of the Nazis when she was liberated at the end of the war; Alan was among the British troops who had freed her and the other inmates. They had just moved to Wales, loving its beauty and remoteness. They asked what I did for a living. I was an historian, I told them, and had recently completed a doctorate on the long-term origins of German women’s support for Nazism. We began to discuss Hitler and, as the conversation progressed, I had an increasingly uneasy feeling that Wanda actually admired him and identified with the Nazis and the Third Reich.

Trying to change the subject, I commented on Wanda’s artwork, which was hanging on the sitting-room walls. Most of her paintings were accurate but rather unimaginative depictions of various species of birds, but interspersed among them were small oil paintings of brightly coloured concentric circles. “Sometimes I just have to paint them,” she said, “I don’t know why.” Their presence was deeply troubling. Not long before, I had read in the Sunday Times colour supplement an illustrated article on art produced in mental hospitals by schizophrenics. It was exactly the same. Walking back to my aunt’s cottage, I asked my girlfriend what she thought. “Did you see her eyes?’ she said, with a shocked expression on her face. “Completely doolally!”

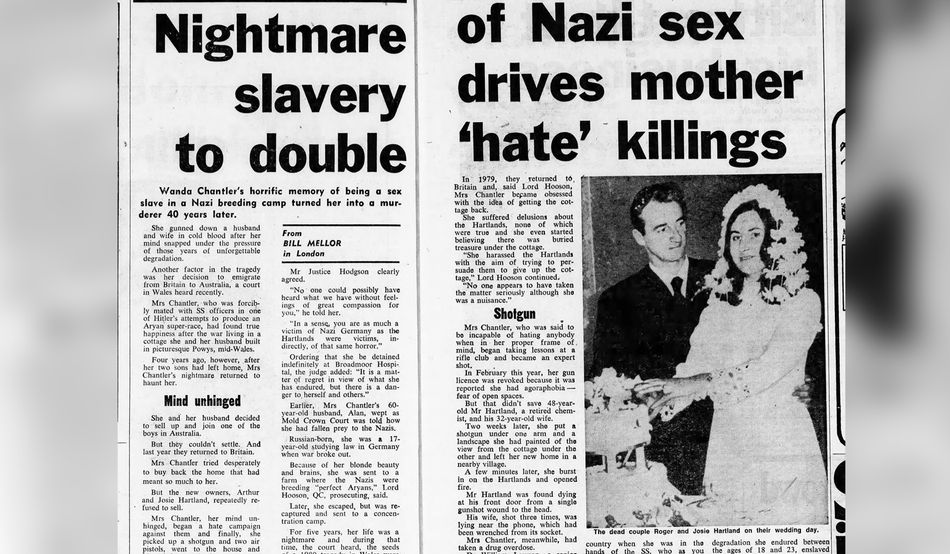

The Chantlers made ends meet by working in Machynlleth, he as a petrol-pump attendant, she as a physiotherapist. They had a son, and a daughter who had trained as a doctor. On another, later visit, bizarrely, Wanda confessed she had thought I lived with my aunt and hoped I would marry the daughter. In fact I never met her, as she had gone to live far away from her parents, in Australia. Alan and Wanda clearly missed her badly, and in 1975 they sold Gellygen Fach to a youngish couple from Birmingham, Roger and Josie Hartland, and moved Down Under to be with her. But things did not work out and, in 1979, Alan and Wanda moved back to Wales. And this is when the trouble began.

Wanda, the dominant figure in the marriage in every respect, began to agitate to get the Hartlands to sell Gellygen Fach back to them. The Chantlers rented accommodation in Machynlleth, and Wanda asked Roger and Josie if they were willing to sell. But the Hartlands had moved to the area for exactly the same reason as the Chantlers, to get away from it all, and in the remote but modernised old farmhouse they had found exactly what they wanted. They said no. Wanda then began to bombard them with abusive and increasingly threatening letters. She began to spread malicious rumours about them. They complained to the police, but were not taken seriously. There was gold buried under the bathroom floor, Wanda claimed; the Hartlands had stolen it. In truth, the only thing under the bathroom floor was the sunken bath.

It emerged that Wanda had been trying to get my fingerprints on the steering-wheel

I was staying with my aunt on one occasion when Wanda drove up in her Mini Countryman, a small estate car. She got out and asked if I would drive her to Gellygen Fach. Her hands were heavily bandaged, and she explained to me that she had injured them and found it difficult to drive. I wasn’t entirely convinced by this, since she had after all managed to drive from Machynlleth. I could see my aunt standing behind her, shaking her head. But in any case, I wasn’t willing to take the wheel. Inside the car was a very yappy dog, standing on top of some blankets in the back, barking away. I had always been afraid of dogs, put off them by the fierce Welsh sheepdogs kept by farmers in the area; they were definitely not pets and, my parents had warned me, should not be approached. Later, it emerged that Wanda had been trying to get my fingerprints onto the steering- wheel, for reasons that soon became tragically clear.

After she had driven back down the hill, my aunt explained to me that Wanda (“that old woman”) had driven up past her house several times, stopping to say hello. Wanda would start driving up the lane in the direction of Gellygen Fach but, my aunt said, “I always follow her, she knows I’ve seen her, and she turns back.” One day, however, she drove straight past, up the hill. My aunt, who was very deaf, was busy and did not notice. Arriving at Gellygen Fach, Wanda got out and waited for Roger and Josie Hartland to return from work.

Approaching the couple when they arrived, Wanda said she wanted to give them a present. It was a painting she had made of the house. But that was not the only thing she had with her. Under the blankets at the back of the Mini were two air pistols and a double-barrelled shotgun. She had obtained them when she had joined a local shooting club, though her licence had been revoked a couple of weeks beforehand, because the club officials had begun to have doubts about her mental state. Grabbing the shotgun, she discharged both barrels at Roger Hartland, shooting him in the face at close range and literally blowing his brains out. As Josie fled into the house to phone the police, Wanda followed her and shot her three times in the back, reloading as she went. Then she took an overdose of pills, and waited for someone to arrive.

Roger Hartland had already warned Alan Chantler over the phone that his wife was driving up to the house, but it was four hours before he arrived and confronted the grisly scene. The police and emergency services eventually came and cleared up the mess. Wanda Chantler’s attempt to kill herself had been as unsuccessful as her attempt to get her old home back. She was arrested and brought to trial but, following psychiatric reports, she was not charged with murder; rather, she was indicted for manslaughter on grounds of diminished responsibility. She pleaded guilty and was sentenced to be confined indefinitely in the secure psychiatric hospital at Broadmoor.

At her trial, Wanda Chantler said she had been traumatised by her experiences as a young woman. Her father in Poland, she said, had sent her to Hamburg before the war to train as a German lawyer. On the outbreak of hostilities, she had been arrested and put into a Nazi “breeding camp” where she had been repeatedly raped by a series of SS men. This was accepted by the judge, who described her as a victim of the Nazis just as much as the Hartlands were of her. It was greatly savoured by the press reporters attending the trial, who were fascinated by this salacious detail. But it was entirely untrue. No such camps existed. There was an SS institution called Lebensborn, “well of life”, which ran maternity homes that would accept unmarried mothers provided they were “racially pure”, but it did not force young women into pregnancy. In any case, there was no evidence that Wanda had given birth before she had her daughter. If she was traumatised, it was by her experience of the Allied bombing of Hamburg in the summer of 1943, which created a huge firestorm, incinerating some 40,000 people in the city.

On the other hand, the Nazis did arrest blonde, “Aryan” Poles, at home as well as in Germany, for “Germanisation”. They were confined in barracks while they were examined above all for political reliability—a scheme set up by SS chief Heinrich Himmler in his capacity as Reich Commissioner for the Strengthening of Germandom. If, as a blonde, “Aryan”-looking young woman, Wanda Chantler had a positive experience being selected as part of this programme it might help explain why she seemed to me to have had such a rosy view of the Nazis. She may have got the idea of “breeding camps”, meanwhile, from a 1961 movie called Ordered to Love, directed by Werner Klingler. The film was set in such a camp, a scenario that had no basis in reality.

Wanda Chantler was eventually released from Broadmoor and went with her husband, who was not held responsible for her crime though he may have been aware of her intentions, to live in Southampton. He died in 2004 and was followed in 2009 by his wife, who died in a care home. The house where the murders were committed still exists, though the Chantlers’ names have been erased from the gable-end plaque. My aunt died in 1998 and her house was sold. Machynlleth continued to decline for a number of years, the main street filled with charity shops and bric-a-brac emporia (my uncle’s pharmacy, HJ Evans Drug Stores, 25 Maengwyn Street, became one such “antiques” store). An attempt to establish a cultural centre (“Celtica”) in the town was a failure. The local school in Pantperthog closed in 1973 and the congregation at the village chapel dwindled almost to nothing as people deserted the surrounding hill-farms. The murder at Gellygen Fach was not the only instance of violence in the area. My aunt’s handyman, who also lived up the hill not far from the old farm, poured petrol over himself and set it alight after an argument with his wife. A farmer across the Dulas valley opposite my aunt’s place shot himself after overreaching financially, having built a new bungalow.

Recently there have been signs of recovery. There’s an annual comedy festival and a Museum of Modern Art in Machynlleth. Tourism has become a more significant source of income, though the area is still somewhat off the beaten track. The school at Pantperthog has been turned into a village hall, but the Edwardian buildings are in need of repair. After the disaster at the South Welsh village of Aberfan in 1966, when a massive slag-heap collapsed and swept away the local school (a calamity in which my young cousin Robert was killed), the mountains of slate spoil that loomed over the village of Corris were levelled and a craft centre was established, inviting visitors to stop where previously they had only ever driven through. Walking in the hills behind my old family farm, I still come across ruined farmhouses and barns. Most of the hippies are long gone, but railway enthusiasts have started to rebuild the narrow-gauge line from Corris and are slowly extending it further down the Dulas valley. It may succeed in attracting much-needed tourism to the area.

The case of Wanda Chantler shows how, many decades later, Hitler’s baleful influence still cast a shadow in the most unexpected places. From the first moment I met her, it was clear that she was a very disturbed individual, and that her mind had been warped by her experiences in Nazi Germany, whatever these were, leading her to form an attachment to her Welsh refuge that was so deep that she could not bear anyone else possessing it. She was certainly not a Nazi, and there was no sign that she shared the Nazis’ ideology, but she seemed to carry with her into her new life a general feeling of admiration for one of the most murderous dictators in history. More than a quarter of a century after the Third Reich had suffered total defeat, its evil was still creeping into the corners of places far removed from its impact, leading to the deaths of entirely innocent human beings.