Britain will be leaving the European Union in March next year, yet we still don’t have certainty on what happens next. Recent documents issued by the government remind us of the risk that we leave without any deal, with tariffs and numerous other barriers imposed on day one. On the other hand, those campaigning for a “people’s vote” believe momentum is gathering behind their cause.

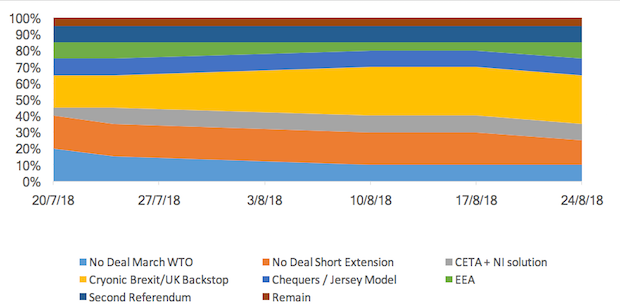

There are thus numerous dimensions to the question of what happens next. Do we definitely leave, is there another referendum, will there be a withdrawal agreement, and what does the long term economic relationship look like? Each of these questions can affect the others: one could imagine a referendum containing options on the long term economic relationship. It can be clearer to simplify all of the major choices onto one chart.

Now technically, as more than one of these things could happen, it can’t really be a probability chart adding up to 100 per cent. But if for the sake of illustration we ignore this, what do we learn from such an exercise?

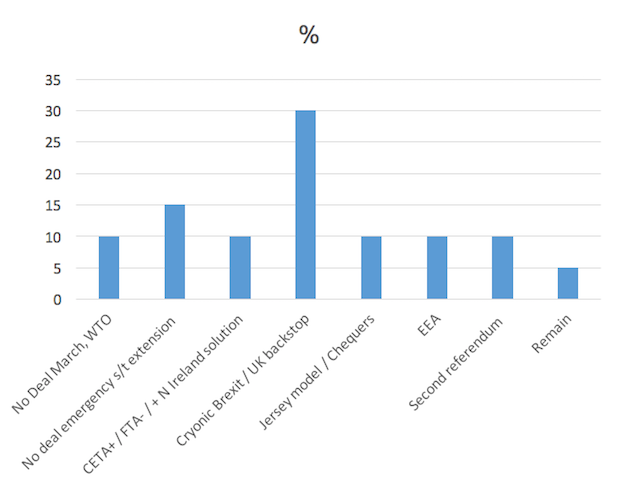

My view is that the single most likely outcome is the “Cryonic Brexit.” In this scenario of potentially endless transition, we leave with a Withdrawal Agreement which operates for as long as the UK and EU take to decide precisely how we can avoid a border on the island or Ireland or in the Irish Sea. We remain for all economic purposes in the European Union, though without much influence. Companies don’t have to make any adjustments but also lack certainty about the future.

This may be the single most likely outcome, but it isn’t a particularly high probability. The EU is at the moment resistant to such an outcome, just as the UK is resistant to a Northern Ireland-only backstop, in which the province remains in effect part of the EU indefinitely, while the rest of the UK is free to complete trade deals around the world. It is currently hard to imagine such an outcome passing through parliament, and on this single issue it may be that the EU shows flexibility in extending a UK-wide backstop. This would involve the whole of the UK remaining tightly bound to the EU until a way forward was found, but might prove more acceptable than what some have tagged rather dramatically the “annexation” scenario.

It is the prospect of the UK and EU negotiators failing to agree on this that leads to a relatively high probability of no-deal. There are a few different varieties of no-deal. One is the reversion to World Trade Organisation terms in March, another is an extension to put in place some very short term agreements in vital sectors such as aviation, and the third is the “no-deal deal,” where there are more arrangements on technical checks, customs and tariffs. This latter form is actually closer to a Free Trade Agreement, and the EU would probably only agree to it with a Northern Ireland backstop, thus it comes within that category.

Some have suggested that a form of no-deal is more than 50 per cent likely, but given moderate conservative MPs such as Nick Boles have explicitly rejected this outcome, both sides want a deal, and the increasing focus on what WTO terms may mean to UK trade, it is surely not quite that high. Though we are consistently warned that it could happen by accident, as without a deal the UK simply ceases to be a member of the EU in March 2019.

The PM’s Chequers plan, along with an EU FTA, or joining the European Economic Area, represent potential future economic relations, which will only be discussed in detail after a Withdrawal Agreement is in place. None as yet have much traction. The Free Trade Agreement, sometimes also called CETA+ after the EU’s Canada Free Trade Deal, would require special arrangements for Northern Ireland to prevent a border. The Chequers plan is unacceptable to the EU as it splits the “four freedoms” (goods, services, people, capital) and isn’t even the full single market in goods, though is close enough for us here to bracket it with the so-called Jersey option which sees the UK remain a member of the single market for goods only. Meanwhile the “Norway option” of joining the European Economic Area/full single market is still prevented by the PM’s red lines, not least on freedom of movement.

Though there will be those hoping to remain, the vast majority of MPs believe the referendum result demands we leave. Yet as we know in politics things can change quickly, and the Labour Party has yet to fully rule out another vote. We also have to take account of the ongoing talks between the EU and UK, with regular formal and informal press briefings providing clues as to progress or not. The general consensus? That the talks are going to the wire.

The trend over the recent weeks in my own view has been away from a no-deal outcome, and towards the cryonic “frozen” Brexit. We must of course have an answer in the coming months. Businesses and individuals affected will be hoping that clarity comes sooner rather than later.