He had never been that keen on Theresa May, but hoped she would at least prove the “grown-up in the room” after the referendum; even as a Remain voter, he says, he could have accepted a sensibly negotiated Brexit. But then came the 2016 party conference in Birmingham, at which May dismissed people who consider themselves “citizens of the world” as “citizens of nowhere,” shallow-rooted types with little interest in what was best for their own country.

“I just thought you don’t actually want people like me in the party around anymore, do you?” says Will, who is in his mid-30s and joined the party under David Cameron. “It made me realise how tribal I had become without realising it. These scales fall from your eyes, and you realise how much bullshit you have swallowed over the years.” After months of soul-searching, he has resolved that at the next general election he will both vote and campaign for the Liberal Democrats. What is unusual about Will is that he isn’t just any voter; he’s a former Conservative parliamentary aide, whose girlfriend is still active in the party.

“I’ve always supported the Tories because I’m a fairly un-ideological, moderate person who just wants reasonable, pro-business policies,” he explains. “But this is a massively ideological project and I think it’s profoundly unconservative, or not my kind of conservatism anyway.”

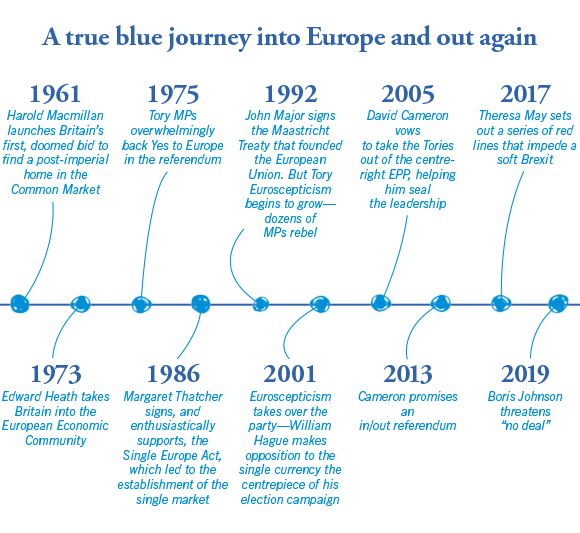

Will is part of a longstanding tradition of pragmatic Tory thinking that abhors the idea of radical beliefs trumping practicalities. It’s a tradition that in recent times has often been defined against doctrinaire Europhobia, but it long predates that—stretching from Disraeli’s early One Nation Conservatism via Baldwin and a post-war revival under Harold Macmillan, to the so-called “wets” uneasy with the socially divisive aspect of the Thatcher years and ultimately to David Cameron, the leader who always insisted there was no such thing as “Cameronism”; no specific ideology, just an understanding of what works.

What worries Will isn’t just the economic consequences of a no-deal departure, but what he sees as hard Brexiteers’ apparent willingness to sacrifice anything—the Union, the queen, the legal and constitutional proprieties trampled in pursuit of a parliamentary prorogation that the Supreme Court ruled unanimously to be unlawful—to get what they want. If moderate Conservatives believe in anything, it is upholding both law and social order: not for nothing was John Major one of the sponsors of that Supreme Court case. “It’s like a midlife crisis,” Will explains, “when you throw everything away in pursuit of something that’s not worth it.” Will, by the way, is not his real name, but his feelings of alienation are both real and increasingly widespread.

While much of the Conservative press, not to mention a Johnson-led Conservative government, frets over votes lost to the Brexit Party, something significant is happening beneath the radar to the 29 per cent of Conservatives who in 2016 voted to Remain. Boris Johnson still pays lip service to them—in this year’s deliberately upbeat, good-humoured party conference speech he boasted of leading a “one nation government” that would focus on schools and hospitals, just as soon as it got Brexit out of the way. But a few good jokes don’t obliterate what is for many moderate Tories an uncomfortable reality. They have spent months being alternately ignored and shouted down, watching as their champions within the party—from Ken Clarke to Amber Rudd, Nicholas Soames to Rory Stewart, who will be standing as an independent to become Mayor of London—were pushed out into the cold or, as in the case of Scottish leader Ruth Davidson, chose to step away.

The quiet exodus of moderate Tories has been masked in the polls by Johnson’s greater success in winning Tory Leavers back from Nigel Farage. But beneath the radar a sizeable minority—not just Remainers but some Leavers who wanted a soft, orderly Brexit and are spooked by talk of a “do or die” departure without a deal—are wrestling with their consciences. Their decisions will shape not only election battles across the country, or the future of a Conservative Party stripped of its soft edges, but also the nature of the parties they migrate towards instead.

“If it was the soft left, if they were the grown-ups in the room, I’d vote Labour. I’d vote for anything that was broadly sensible”

Tory Remainers first started jumping ship in significant numbers this spring, after it became clear Britain wouldn’t be leaving the EU by March after all. One in eight people who had voted Conservative in the 2017 general election swung to the Lib Dems in May’s European parliament elections according to polling by the former Tory donor Michael Ashcroft; and for the two thirds who said they had no intention of going back at the next general election, it was clearly more than a protest vote. In July, after Boris Johnson and Jo Swinson were respectively elected leaders of their parties, the number of Tories switching to the Lib Dems immediately doubled in YouGov’s Westminster voting intention tracker. But it’s the drama of the last few weeks that seems to have dislodged something bigger.

At the beginning of September, 51 per cent of Conservative Remainers were still planning to stick with the party in a general election, according to the pollsters Opinium. By the end of September, following the Supreme Court ruling and a brewing scandal over Boris Johnson’s alleged affair with an American model-turned-entrepreneur given £126,000 of public money while he was Mayor of London, that figure had fallen to 42 per cent. Another 33 per cent would vote Lib Dem and 19 per cent preferred “some other party” as yet undefined (the pool in which any kind of En Marche-style movement, such as the one the former leadership contender Rory Stewart has hinted he might one day seek to lead, would probably be fishing).

The referendum and its aftermath have, of course, blown many things around, but nothing further or faster than Conservative MPs. Only three years ago, 185 of its MPs—a clear majority—were declared for Remain; this autumn 286 of them—over 90 per cent—fell into line, even if often reluctantly, with Johnson’s demand to keep the hardest of hard Brexits on the table. And in the move from “what works” to “do or die,” the broad Tory church may have narrowed beyond the point where much of the congregation is comfortable.

The new breed of alienated Tory tends more towards younger urban graduates than retired colonels from Dorset, and many will have been drawn to David Cameron in his husky-hugging years, when he asked his party to “stop banging on about Europe.” Broadly socially liberal but economically cautious, they worry about NHS waiting times but also knife crime and poor behaviour in schools. They probably wouldn’t have been drawn to the oppositionalist, sandal-wearing Liberal Party of the old days, but will very much have been comfortable in coalition with Nick Clegg. They regarded austerity as an unfortunate but necessary business, and—after the shock of the referendum result—they had assumed May would sort out some kind of compromise. Because, above all, these are people who expect a Conservative government to put prosperity first, manage competently and let them get quietly on with their lives in peace. They were shocked by reports of Johnson crying “fuck business!” in response to warnings that businesses didn’t want hard Brexit, and would have preferred Stewart or Jeremy Hunt for leader this summer.

Many thoroughly approved of the sacrifice made by Stewart and the other 21 Tory MPs who lost the whip this summer for defying Johnson over a no-deal Brexit. “I have for years been screaming at the TV “do what’s right not what’s easy” and I felt they were being hugely self-sacrificing,” says Gabriel Rozenberg, a Conservative councillor in the north London borough of Barnet who defected to the Lib Dems shortly after that rebellion. “I thought ‘if I was an MP, I would be one of them.’”

For many such moderate Tories, the final straw seems to have been the election of Johnson on a no-deal Brexit ticket, seen as a sign of something new and dangerously radical taking total control of the party’s mainstream. The Conservatives have embraced divisive and sometimes extreme policies in the past. The real twist this time is a grassroots clamour for doctrinal purity, with all but true believers in Brexit cast out, which the leadership is doing nothing to challenge.

What makes the next election wildly unpredictable is that many fear a similarly doctrinaire zeal has overcome the official opposition. Despite his background working for a Tory MP, Will could easily have voted Labour, he says, if it wasn’t led by Jeremy Corbyn: “Even if it was soft left, if they were the grownups in the room I’d vote for them. But this is what’s happening because of Corbyn; this crisis is only a crisis because there isn’t an opposition that could take over. I’d vote for anything that was broadly sensible.”

That word hints at a new divide opening up in British politics between what the University of Warwick researchers Mirko Draca and Carlo Schwarz call anarchists—people frustrated with the pace of political change, drawn to radical ideas about smashing everything up and starting over—and centrists who value managerial competence and stability. Remarkably, the anarchists are more common on the British right than left, according to Draca and Schwarz, but still outnumbered nationally by centrists.

What remains to be seen is whether there are enough of the latter in the right places to swing an election. Will lives in Islington South and Finsbury, a Labour seat the Tories were never going to win anyway (although it has in the past been marginal to the Lib Dems, and squeezing the Tory vote could help them). But his parents, both lifelong Conservative voters vowing not to vote Conservative this time, live in rural Gloucestershire; a county which in the Cameron years was pretty solidly Tory, but is no longer so predictable.

This summer, Max Wilkinson was out knocking on doors in the spa town of Cheltenham when he suddenly realised he had been down this street before. Years earlier, as a keen young Lib Dem activist, he’d canvassed in this ward—an enclave of rather smart stucco-fronted Georgian terraces near the park—and found one lonely supporter in a street of Conservative households. Not this time.

“People were denying they’d ever voted Conservative,” says Wilkinson, now the Lib Dem parliamentary candidate for Cheltenham, over a pot of tea in a town centre café. “People in that street just don’t like Boris Johnson. I’ve canvassed people who have voted Tory in every election in their life who don’t like Boris. They think he’s a bit of a joke, they don’t see substance.”

What they want, he thinks, is a safe pair of hands and no nasty surprises, which is why the threat of a no-deal Brexit alarms them. (In August Alex Chalk, the local MP who is defending a slim majority of less than 3,000, was filmed on the doorstep of his constituency office trying to reason with a crowd of protestors angry about prorogation.) “People here vote Conservative because they think they’re the sensible people. Well, we’re the new sensible,” says Wilkinson, a former sports reporter. “Respect for the rule of law, respect for the great establishments of the state, a feeling of chaos—those are the triggers for a lot of people who are swinging from the Conservatives to us.”

But it may help, too, that towns like this are less staid than they may seem. Cheltenham may be synonymous with boarding schools, horse racing and spies from GCHQ but the promise of good state schools and the Cotswolds on their doorstep has lured in young families leaving London; you can commute to Bristol, and it has its own mushrooming creative and tech sector, although it also has pockets of deprivation around the edges. Tories here, says Wilkinson, are “probably at home with things like equal marriage and gender equality and concern for the environment.” And that’s not just true of Remain-voting Cheltenham, or the more bohemian and also Remain-leaning Stroud nearby, where former Conservative MP Neil Carmichael recently defected to the Lib Dems. Because in seats of many different sorts there are plenty of voters who have always thought of themselves as “sensible” first and Conservatives only second.

“What they want is a safe pair of hands and no nasty surprises, which is why the threat of a no-deal Brexit alarms them”

Leaving London, a law unto itself electorally, aside for a minute, the new battleground lies roughly south of an imaginary line from Bristol in the west to the Wash in the east. Resurgent Lib Dems are pushing back in their former West Country strongholds, even though most of these places—Yeovil, Devon North, St Ives—plumped for Leave in 2016. At the same time, they are advancing on a clutch of comfortable, Remain-voting Home Counties towns; the Essex grammar school town of Colchester, St Albans in Hertfordshire, Wokingham in Berkshire and swathes of Surrey commuterland. When Guildford’s Tory MP Anne Milton rebelled over Brexit, warning Johnson that the seat would fall if he didn’t change tack, he is said to have retorted that in that case “Guildford will have to go.”

A more serious yellow surge could leave seats like Esher and Walton, home to hardline foreign secretary Dominic Raab, vulnerable too. What makes this election harder to predict than the usual scrap between Labour and the Conservatives, says one veteran election strategist, is that in a more fractured four-way contest small changes make a big difference; if the Lib Dems break through the 20 per cent barrier, even a percentage point here or there could deliver some shocks. And just a handful of seats changing hands could be crucial given the fraught and closely-balanced arithmetic in parliament.

The wild cards, meanwhile, are the unusually high number of seats where sitting Tories have lost the whip. There is no consensus among the 21 rebels and the handful of other MPs who have individually peeled away; some are retiring from parliament but remaining loyal to the party, like Nicholas Soames, while others may yet follow former justice ministers Sam Gyimah and Phillip Lee to the Lib Dems. Some hope to return to the Tory fold before the election, but there is feverish speculation about others running as independents, although the implosion earlier this year of the breakaway centrist party Change UK means most Tories now assume any broader shake-up of the party structures will not emerge until after a general election.

When so much is up in the air at once, there are no guarantees. For all the unpopularity of Corbyn and the stark division within Labour, one serving Tory minister predicts Johnson will struggle for an overall majority even if he does deliver Brexit: “We’ll lose most of the 21 rebels’ seats, all the Lib Dem marginals—I think we lose 30 to 40 seats. Up north the Brexit Party will take a chunk out of Labour, not us, and we might scrape through in five to 10 seats. I think we’ll have a hung parliament.” The 13 seats the Conservatives won in Scotland, partly due to the centrist appeal of Davidson, will also be at risk—Johnson and “no deal” are particularly unpopular in a nation that voted to Remain.

But if some of those lost seats will be traceable directly back to Johnson’s divisive leadership, this story didn’t start with him. We may be seeing only in retrospect quite how fragile and unfinished David Cameron’s modernisation of the Conservative Party was; how quickly, and how thoroughly, the last Tory since Major to win a majority could come undone.

What makes Cameron’s recently published memoirs, For the Record, unexpectedly revealing is that they’re based on taped conversations with the journalist and Tory peer Danny Finkelstein throughout his time in office. As Finkelstein has said, this pins him down more closely to what he thought at the time, rather than what he thinks with the benefit of hindsight.

And the striking thing is how little inkling he had of his coming downfall. Cameron may have thought of himself as a One Nation leader, but there is no sign that he understood the pain austerity was causing in parts of the country, nor the damage it could do to Tory reputations: he writes of Ed Miliband’s “lazy attack that deficit reduction hurt ordinary people.”

This nonchalant leader also asserts (but never actually establishes) that the referendum he called was inevitable, and betrays a complacency in the renegotiation that went before it; having won concessions in the past, he seemingly couldn’t grasp that European patience with Britain’s constant demands for special treatment might wear thin. But the more fundamental problem was his failure from the start of his premiership—in the words of defecting councillor Gabriel Rozenberg—to do what “Conservatives are supposed to do: come up with a narrative to defend the status quo.” Cameron seems to have wrongly assumed most Tories felt as he did about the EU—periodically irritated, but not enough to walk away from the economic benefits. Having never bothered making a positive case for Europe before the referendum campaign, Cameron shouldn’t perhaps have been so surprised when Conservative voters concluded there wasn’t one.

Indeed, what really leaps off the pages of For the Record is his misreading of his own party. As early as 2011, Cameron notes his surprise on discovering “a large part of the new intake—modern, compassionate Conservatives—who were more stridently Eurosceptic than I had expected.” Even as the referendum campaign begins, he is taken aback to find “MPs, friends, local party members and councillors who I had never heard express the view that we should leave the EU waxing lyrical.” His attempts to talk round pro-leave Cabinet ministers prove “far harder than I had anticipated. The latent Leaver gene in the Tory Party was more dominant than I had foreseen.” Theresa May’s advice to George Osborne when she fired him was to get to know his own party. She could just as well have said the same to Cameron.

What he did see, however, was that part of his party was never truly reconciled to his leadership. As his chief of staff Kate Fall once warned him, he writes, “They don’t love you. They will tolerate you as long as you can win.”

Adam Sykes, a moderate former constituency association chair from Wirral South in Merseyside, observed the same thing from the grassroots. “Everyone didn’t become a ‘modern’ Conservative the day Cameron became leader,” says Sykes, who himself joined the party in 2005 inspired by talk of root-and-branch modernisation. “Some people didn’t even want his [Cameron’s] picture up in the constituency offices. I had to keep Margaret Thatcher up as well as a compromise.” As a Remainer, he was taken aback by the referendum result, but stuck around long enough to stand unsuccessfully for parliament in 2017. This spring, however, he quit as a councillor, and now runs Movement46, an umbrella organisation for Tories alienated from their own party but undecided on where to go next. (The name refers to 1846, when the Tory prime minister Robert Peel broke with the landed interests in his own party to repeal the Corn Laws in a bid to ease famine in Ireland; his party was mostly out of power for a generation, but his followers ultimately helped found the Liberal party.)

“Even if Boris goes, they’ll vote in Jacob Rees-Mogg or Steve Baker or whoever”

Sykes has lost hope of changing the party from the inside, believing moderate Tories are now horribly outnumbered in an unrepresentative grassroots party. “People have busy lives, so people who join political parties have got to really want to do something, they’ve got to be passionate. And that’s not necessarily the same as people who vote for the party. I just don’t think we have got enough moderates.” He describes a phenomenon that some longstanding Labour members may recognise; an increasingly ideological, angry membership driving gentler souls away, consolidating power in the hands of hardliners. Groups like Movement46, along with private social media networks like the One Nation Conservatives Grassroots WhatsApp group, can provide those fleeing with temporary shelter. But none yet show signs of being nascent political parties and there is little, if any, agreement on a permanent home.

On a sunny September weekend, shortly after 21 Tory MPs lost the whip, a group of somewhat beleaguered one nation Conservatives gathered in Spitalfields, east London, for a history lesson from one of their number.

His own hunch, Ken Clarke told the conference organised by the moderate Tory Reform Group, was that the Conservatives would ultimately stop short of a second great Peelite schism: “The Conservative Party has always had a nervous breakdown when you mentioned the word ‘Europe’ throughout my career, but as soon as you stop mentioning the word ‘Europe’ it’s quite a cohesive party.” But the party was, he said, “under great strain. We won’t really know until after the election.”

The problem Clarke described that afternoon is that, with an electoral system that punishes splintering, British parties have always had to contain multitudes, bringing together factions that in other European countries would be split between several smaller parties. The advantage is that British governments usually come ready-assembled, rather than having to be bolted together via coalitions, because party leaders do the hard work of reconciling differences beforehand. Thus Labour somehow managed to accommodate both George Galloway and Tony Blair, the Tories both Clarke and Bill Cash. But what if that’s no longer possible?

From the top to the bottom of the party, moderate Tories are now dividing between those determined to stay and fight, and others who are beginning to whisper about PR, as they wonder if it’s time for some new breakaway movement. Former Tory minister Nicholas Boles, who was deselected by his local party after a long-running clash of wills over issues including Brexit and now sits as an independent, has come out for change, tweeting recently that a “shake up” of the political system “is long overdue.”

On the other side are Tory activists digging in for the long haul, as well as the Nicky Morgans and Matt Hancocks, still serving in a cabinet that seemingly contradicts everything they once stood for. (Morgan was reduced to tweeting that she knew the PM was “sympathetic about the threats” MPs faced after Johnson had dismissed anxieties about them as “humbug” in the Commons.)

Neither road is easy; resistance can lead to de-selection or whip withdrawal, collaboration to bitter recriminations from moderate friends and family. “Some of my colleagues have taken the view that to be in government means we are legitimising no deal, that we’ve been hoodwinked,” says one pro-Remain minister who hangs on thanks partly to a belief that Johnson really wants a deal, and partly to a stubborn conviction that if the zealots want the moderates out, then the last thing they should do is leave. “I decided that Boris deserved the benefit of the doubt. But at what point do I let the facts change my mind?”

And the same dilemma reaches all the way down to the grassroots, where some lonely pragmatists have already reached the point of no return, unable to face the thought of campaigning in a general election for a party they don’t think deserves to win. “The membership that voted substantially to Leave are in charge of this party now and I profoundly disagree with the membership,” says departed councillor Rozenberg. “Even if Boris goes, they’ll vote in Jacob Rees-Mogg or Steve Baker or whoever.” For our former parliamentary aide Will, as well, there’s no way back, and even the thought that voting Lib Dem to stop a hard Brexit might let Corbyn in doesn’t deter him: “They’re both radical ideological disasters.”

Others do still just about see a way back home. Patrick Moore, a 44-year-old from Shipley in Yorkshire, was put off the Lib Dems when they started calling baldly for Article 50 to be revoked. He was happy enough with May’s deal, and a part of him had even hoped Boris Johnson might be the one to persuade parliament into accepting it. He “would happily vote Tory again,” if and when the more hard-line ministers are “replaced” by people like Stewart.

And others again will be wrestling with their consciences all the way to the ballot box. Back in Spitalfields, Clarke had one final piece of advice for an obviously conflicted young woman. “Keep your cool, sound reasonable, and don’t abandon your principles,” he told her. Right now, that’s perhaps easier said than done.

Join the newly-independent MP and London mayoral hopeful, Rory Stewart, and the Observer’s former Political Editor, Gaby Hinsliff, on 25th Nov to discuss whether moderation is now finished as a force within the Conservative party.