You don’t get to lead a democracy, let alone get re-elected by a landslide, without a mandate to save your country. What distinguishes the Indian prime minister Narendra Modi is that he is a cult salvationist—yet, after seven years leading the world’s biggest democracy, he has little to show beyond the accumulation of votes.

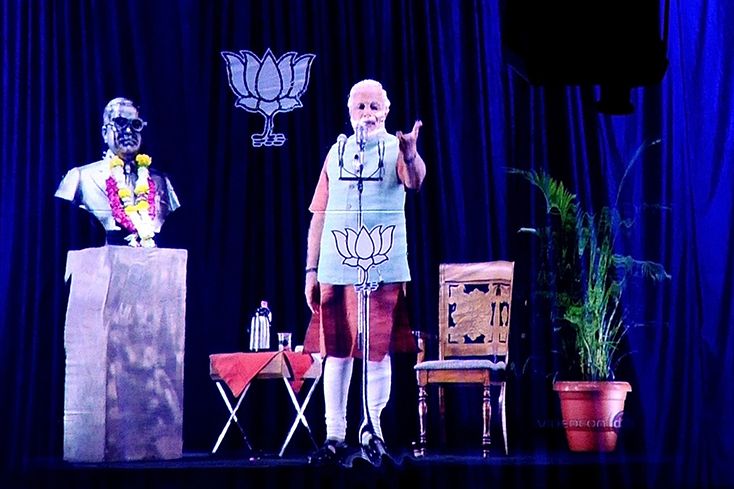

As an outsider distilling the avalanche of controversy, hagiography and verbiage, I am struck most by Modi’s congenital ambivalence. This is a thoroughly 21st-century party leader beamed as a 3D hologram into thousands of election meetings and rallies, fiercely partisan and constantly accusing his opponents of disloyalty to India. Yet he is also a man who decamps to a cave mid-campaign (cameras in tow) to contemplate the meaning of life and impart spiritual wisdom. While earning rapt adoration, of course.

This ethereal hologram—brutal modern politician as prophet and guru—has won two successive election landslides across a vast, extraordinarily diverse country of 1.3bn people. But who is the real Modi? In trying to find out, I kept coming back to three key questions. Which country does he see himself as leading: India or Hindu India? Is he saving Indian democracy or is he subverting it? And is he, as he insists, a true economic moderniser—or a fanatical religious nationalist for whom modernisation is a tool to assert supremacy, with reforms proposed, chopped and changed for sectarian advantage?

I have come to the view that these questions can’t be resolved, unless he lurches to extremity thereafter, because chronic ambiguity is Narendra Modi. A fervent Hindu militant in his teens, he now operates within a quasi-western political framework he half accepts and half rejects but has not sought—or at least has not yet been able—to fundamentally change.

Ambiguity is in India’s DNA. Since its refoundation as an independent state in 1947, its prime ministers have been a mix of “strong men”—plus one strong woman—and weak caretakers. They have ruled a just-about democracy characterised by multi-party elections and formal constitutional liberalism but equally by extreme instability and endemic political violence—including regular assassinations—all flowing from two bitter centuries of British imperialism.

Modi’s western admirers call him the Thatcher of India, and claim he is reversing 70 years of state regulation. This is risible given his paltry and contradictory economic record, starting in 2016 with the chaos of a botched demonetisation: removing 86 per cent of cash from the economy overnight, for no good reason. He also claims to be founding a “second republic,” replacing the one forged by the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty. Yet while Modi has defeated the latest gilded Gandhi—Rahul—twice, and may have ended the family’s political ambitions, I am struck by his resemblance to Rahul’s grandmother Indira. Prime minister for most of the two decades (1966-1984) between Modi’s formative 16th and 34th years, Indira was similarly contradictory on both democracy and reform. She lurched in crisis to an “emergency” dictatorship in 1975-1977, then drew back and ultimately sustained her father Jawaharlal Nehru’s democratic edifice.

“At just 17, Modi effectively dissolved his arranged marriage, unconsummated. He has been celibate ever since”

In his mid-twenties, Modi was an underground runner in the resistance to her “emergency.” Ironically, his rule since 2014 has itself been called an “undeclared emergency.” This is inaccurate: he hasn’t resorted to the draconian repression and mass imprisonment of opponents of Indira’s 21-month dictatorship. But the constitution has been pushed to the limit and manipulated, as under Indira and her son Rajiv, from the blocking of social media to the arrest of journalists and even a comedian, through to localised violence with a nod and a wink from Modi’s minions, and the suborning of the Supreme Court, the state media and the Electoral Commission.

Then there are Modi’s peremptory “modernisations,” accompanied by alternating aggression and retreat: the latest is an increasingly botched “big bang” deregulation of agriculture, India’s largest industry. Again this is eerily reminiscent of Indira, whose pièce de résistance was a mass forced sterilisation campaign spearheaded by her other son, Sanjay, carried out in the name of modernisation.

Modi’s India, like Indira’s, is in many ways a continuation of the republic founded by Nehru 74 years ago. It has all the tensions and contradictions embodied in Nehru himself, a Harrow- and Cambridge-educated barrister turned freedom fighter and authoritarian ruler. This republic is in parts socialist, elitist, democratic, secular and Hindu, nurturing a dynamic and sophisticated middle class, yet perpetuating massive inequality and divisions.

But in defining himself against what came before, Modi offers two populist twists—abandoning the inclusive language of secularism to rally the religious majority against India’s huge minorities, and rallying anyone feeling downtrodden against the old elite, and most especially the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty. Breaking from hereditary rule sounds like progress, but whether it turns out to be will depend on how Modi organises his eventual succession, and whether he hands over to one of the more extreme Hindu nationalists in his political “family,” like his right-hand rottweiler Amit Shah, home affairs minister.

On the spectrum of contemporary populists, Modi is more proletarian, professional and indeed popular than Erdoan of Turkey and Bolsonaro of Brazil, and leagues more so than Trump. He is a vigorous 70-year-old whose tenure has no end in sight. Rahul Gandhi resigned the leadership of the opposition Congress Party 20 months ago with many of its members, nationally and in state assemblies, having in effect defected to Modi’s party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Modi’s brand of populism is described by Arvind Rajagopal of New York University as a simulacrum: “a media artefact regarded as more true than any amount of information and, in fact, capable of correcting that information. Modi is the leader who will drag the country out of its trouble and propel it to greatness: accepting this basic premise amounts to political realism today.” Or as Neelanjan Sircar of Ashoka University puts it: “The murkier the data, the easier it is for him to control the narrative.”

But three artefacts of the Modi phenomenon are truly solid. First, his journey from poverty to power. His rise from the bottom half of Indian society is unique in a country historically ruled by moguls, princes and—for the first half-century of independence—largely through one family.

In India’s labyrinthine caste gradations, Modi is an OBC (“Other Backward Caste”): a sort of lower middle class. His dad was a chaiwala (tea vendor) with a stall on the station platform in small-town Vadnagar, sustaining a family of eight in a three-room house without windows or running water but able to get his children a decent education. In Indian terms, Modi’s background is similar to Joe Biden’s, another son of a struggling lower middle-class small-town salesman (of cars). At school both had a love of debating, argumentation and, say contemporaries, a propelling stubbornness.

Secondly, Modi’s mission is power, not money or dynasty. Although he courts and is courted by the Hindu mega-rich who fund his party at home and abroad, especially in Britain and the US, he does not enrich himself or his relatives. “I am single: who will I be corrupt for?” is one of his lines. An arranged marriage was effectively dissolved by him, unconsummated, when the ascetic teenager abruptly departed Vadnagar, aged 17, on the first of several nomadic nationwide quests. He has been celibate ever since. As monk-leader, implacable yet worldly-wise, he reminds me of both Archbishop Makarios, priest-founder of independent Cyprus, and Lee Kuan Yew, authoritarian guru-founder of Singapore. “Dynasty or democracy,” one of his 2014 slogans, successfully branded Rahul Gandhi a “prince” (shahzada). Another saying of his was “I am proud I sold tea, I never sold the nation,” which struck home.

Thirdly, Modi has an electoral Midas touch. No one else in history has won a total of nearly half a billion votes in fairly free multi-party elections—and he isn’t done yet. His BJP is the world’s largest political party, claiming 100m members: twice the size of the Chinese Communist Party. Two huge national victories since 2014 followed three equally sweeping elections as chief minister of his native Gujarat, a state bigger than England on India’s northwest coast. In 2014, he nearly trebled the BJP’s tally in the directly elected Lok Sabha (lower house) of the Indian parliament, giving the party, which everyone had assumed was fated to remain a perpetually minority party, its first ever overall majority. It was also the first single-party government of any party in India since the 1980s. The BJP has now become Modi’s party in the way that New Labour was Blair’s and Germany’s CDU became Merkel’s—only much more so.

But it is important to understand that Modi is not a De Gaulle or even a Macron who summoned his own political force into being: his rise came through a movement which had deep historic and cultural roots, even if he has transformed its appeal. Like so many of the world’s election winners, Modi has been a professional politician since his twenties. He started as an apprentice in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a religious nationalist movement which believes in the essential Hinduness of India—an ideology known as “Hindutva”—and went on to join the BJP, founded as the movement’s modern political wing in 1980. He started in the army of RSS volunteers before becoming an organiser, after which he was drafted to become chief minister of Gujarat amid a leadership crisis in the local BJP.

Modi knows India, socially and geographically, better than perhaps any other Indian alive, and from the bottom up. He has mastered modern democratic arts and his ubiquitous social media presence includes a Modi app, flashing up every speech, event and opinion to millions with a professionalism that leaves Trump in the gutter. “India saved itself with a timely lockdown, travel restrictions, shows recent study. Read more here!” runs the latest notification on my phone, the fourth of today.

“Speaking in Hindi, Modi is the finest speaker I have ever heard; his oratory is mesmerising,” one opponent who does not wish to be named tells me. To my surprise, given his dictatorial reputation, he is a considerable parliamentarian, capable of graceful tributes to opponents, albeit only when they are retiring or have been defeated. “We stand for those who trusted us and also those whose trust we have to win over,” he declared after his 2019 landslide. His bitterest political critics typically pay tribute to his skill and crave his attention even as they attack him.

Each day features another socially distanced mass Modi event, typically in a different state. Whether launching a toy festival in Delhi or a railway scheme in West Bengal, the white-bearded sage declaims an impassioned homily combining a political message with spiritual guidance and lifestyle advice. Addressing newly graduating doctors, after thanking them for their efforts in the pandemic, he urges them to “keep a sense of humour, do yoga, meditation, running, cycling and some fitness regime that helps your own wellbeing,” and invokes Hindu saint Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa’s mantra that “serving people is the same as serving God.” “In your long careers, grow professionally and at the same time, never forget your own growth. Rise above self-interest. Doing so will make you fearless,” he preaches.

“Modernisation not westernisation” is another Modi slogan—he has a slogan for everything—yet his political packaging, including that hologram, is done with the help of slick BJP professionals trained in Britain and the US. He plays the west, using the right language and commandeering the wealthy and influential Hindu diaspora like an army. Britain’s populist Home Secretary Priti Patel, a fellow Gujarati, jokes with her friend “Narendra” in Gujarati. He calls virtually every western leader “my friend,” and they reciprocate. Whatever their concerns about sectarianism, western leaders desperately want the Indian leader onside. After his inauguration, Biden called Modi before Xi Jinping: escalating crises in Myanmar, Afghanistan, Hong Kong, Taiwan and the South China Sea give the prime minister leverage, which he shrewdly exploits.

But is Modi within or beyond the pale? In his personal language generally within—although under his rule an anti-Muslim and anti-secular culture war has been stoked, amplified by Amit Shah and BJP activists. Yogi Adityanath, a Hindu priest cloaked in saffron robes and the BJP chief minister of the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, infamously proclaimed: “If Muslims kill one Hindu man, then we will kill 100 Muslim men.” Modi himself doesn’t go there: modernisation and Hindu ancestor worship are his public rhetoric, and he rarely attacks opponents for much more than being divisive and unpatriotic, which is pretty much what British Tories have been doing for two centuries. And yet, in front of parliament in February, Modi called the farmers encamped in Delhi protesting the new laws “people who cannot live without protests,” and—more chillingly—“parasites.”

The BJP culture war is increasingly vicious, seeking to erase India’s Mughal past and repress Muslims in the present by renaming towns and cities, rewriting and “saffronising” Indian history, and asserting cultural, religious and legal ascendancy, including through beef and alcohol bans. In the Hindutva mind, “their” India has been invaded twice, by the Muslims and then by the British, and both invasions need to be repelled. A defining event was the BJP-inspired 1992 attack on the Mughal-era Babri mosque in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh. Demonstrators razed it to the ground and attempted to erect a Hindu temple to Rama, an event which radicalised the whole Hindutva movement. This is the backdrop to Modi’s discriminatory social and cultural policies—in 2019, the Supreme Court ordered the site of the demolished mosque be handed over to Hindus to build a new temple—as well as his symbolic gestures, like his scheme to rebuild Lutyens’ colonial complex in New Delhi.

The big question, though, is whether Modi is not only sectarian, but also an outright inciter of violence and underminer of the constitution. Here four charges are laid. First, that in early 2002, shortly after becoming chief minister of Gujarat, he stoked a Hindu-on-Muslim pogrom in reaction to the murderous attack by a largely Muslim mob on a train passing through Godhra, in Gujarat, conveying Hindu pilgrims from Ayodhya.

Second, there is the 2019 imposition of direct rule from Delhi onto the country’s one Muslim-majority state, Jammu and Kashmir, which neighbours Pakistan. Third, a new citizenship law, also introduced in 2019 shortly after his re-election, giving Hindu but not Muslim immigrants a fast track to Indian citizenship. And fourth, the current farm reforms, which have anti-Sikh overtones because they particularly affect Punjab, “the breadbasket of India.”

Poring over accounts of these four cases, my verdict—surprise, surprise—is that Modi’s responsibility for bloodshed and excesses is ambiguous. It is what happened in his penumbra, rather than by his explicit or overt direction, which is so murky. During the 2002 Gujarat riots, more than a thousand were killed, mostly Muslims, with 200,000 people displaced and 230 historic Islamic sites vandalised or destroyed. No national official inquiry indicted Modi, even though his opponents were running the government in Delhi, and there was no repetition in the next 12 years of his chief ministership. But it was on his watch, and some of his associates were implicated and prosecuted.

In Jammu and Kashmir, communal strife long predates Modi. Nehru unilaterally asserted sovereignty over most of the briefly independent state in the 1950s, before partitioning it jointly with Pakistan. The 2019 imposition of direct rule, a BJP manifesto pledge, followed decades of endemic instability and paramilitary outrages on both sides, akin to Northern Ireland during the Troubles. Nor has democracy been entirely suspended there. Multi-party elections in the region continue, including ones announced for a new Jammu and Kashmir legislative assembly.

Of the four charges, the anti-Muslim citizenship reform is the most partisan, and entirely of his own making. It is targeted mainly at Bangladeshi immigrants, but lies within the ambit of democratic decision-making. It is a less sweeping alteration to immigration than Trump’s anti-Mexican measures and far less than the UK government’s abolition of free movement of people to and from the European Union, even if the religious sectarianism is obviously a

distinct aspect.

“In the Gujarat riots, over a thousand were killed, with 200,000 displaced and 230 historic Islamic sites vandalised”

Modi’s farm reforms are ambiguous for a different reason. There is no disputing their legitimacy in principle. Independent observers and modernising politicians, including Modi’s Congress Party predecessor Manmohan Singh, the Oxbridge-educated Sikh economist who made his name as a deregulating finance minister in the 1990s, have long urged and periodically attempted the liberalisation of India’s command-and-control economy, including its agriculture. Reforming an ossified regime of “minimum support prices” and state “agricultural produce marketing committees,” or introducing private agri-purchasing companies, is not wrong or inherently partisan.

There are accusations that BJP-supporting middlemen will reap fortunes and screw over the farmers, and the handling of the farmers’ protests in Delhi has been terrible. However, as journalist Shekhar Gupta puts it, the first-order issue isn’t the legitimacy of the reforms—“at various points in time, most major political parties and leaders have wanted these changes”—but rather the executive incompetence that means they have been so mishandled, watered down and delayed that they will probably make little impact. “The Modi government has lost the battle for these farm laws,” he writes. “These laws are… dead in the water.”

The chaos is par for the course for Modi’s “modernisation.” The disastrous 2016 demonetisation, a populist but unjustified attack on “black markets,” was followed by a new goods and services tax (GST), forcing small businesses to digitise their payment systems, despite chronically poor preparation and support. Four years later, medium-sized and small businesses, the backbone of the Indian economy, are still struggling. India’s unemployment rate was 3.4 per cent when the GST was introduced in July 2017. It is currently over 8 per cent; even before Covid-19, growth had stalled.

As for Thatcherite-style privatisation, it might be controversial if it had actually happened but, wary of opposition and loss of patronage, Modi’s biggest privatisations are announced and re-announced but don’t take place. The next ones are supposedly of Air India, hardly a good post-Covid prospect, and of as yet unnamed public-sector banks. It is the same story—namely the lack of any consistent story—with international trade. The seminal moment was in November 2019, when at the last minute Modi pulled out of a trade deal with the 15 Asian members of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, leaving China supreme in the organisation. Ditto with industrial policy, which oscillates between liberalisation and protection. The latest incoherence is two trillion rupees ($27bn) in “production-linked incentives” to assorted domestic and foreign firms for a period of five years.

Asian economic commentary is no longer about the (always disputed) “Gujarat miracle” that Modi was going to transplant from one state to the whole country. Gone is the talk of a delayed continuation of Manmohan Singh’s modestly deregulatory 1991 budget with its grand paraphrase of Victor Hugo: “No power on earth can stop an idea whose time has come… the emergence of India as a major economic power in the world happens to be one such idea.” The discussion now is about post-Covid China again accelerating away from India economically, when the per capita income of this colossal neighbour is already several times higher. And about the consolidation of “crony capitalism” as business backers of Modi’s—like India’s wealthiest man Mukesh Ambani and fellow billionaire Gautam Adani—get richer while nothing changes for ordinary Indians. Even the campaign to “sanitise India,” ending open defecation in rural areas, has stalled.

The god Rama is the ultimate Hindu embodiment of the supreme values of love, compassion and justice. Modi claims to stand for a new “Rama Rajya,” invoking Mahatma Gandhi. But the Mahatma, before he was assassinated by an RSS militant, wrote: “By Rama Rajya I do not mean a Hindu state. What I mean is the rule of God,” where the weakest would secure justice. He was unambiguous about that: not a hologram.