Never underestimate the capacity of Boris Johnson to win from a tight corner, and all his corners are tight. In his 13 years at the top of politics, since he became mayor of London in 2008, he has despatched all his rivals in dramas whose common theme is the extraordinary self-belief, exhibitionism and sheer entitlement of the Prime Etonian.

Prime ministers Cameron and May, opposition leaders Corbyn, Swinson and Farage, Mayor Livingstone, a litany of chancellors, foreign secretaries, ministers, MPs and permanent secretaries—all lie side by side in the Westminster graveyard, joined recently by pre-eminent adviser Dominic Cummings. Keir Starmer, an initially promising Labour leader, is on the danger list. No duty or person instils obligation—not the Queen, brazenly manipulated en route to the 2019 election, not the brother Johnson drove out of the Commons before installing in the Lords, and not the wife he swapped for a younger one, like Catherine of Aragon for Anne Boleyn, while occupying the supreme office.

In terms of accumulated political power, post-vaccine Boris rivals post-Falklands Thatcher and pre-Iraq Blair. So it is time to take the Johnson phenomenon seriously and explain it. Here goes, from one who knows him fairly well. Boris isn’t a conventional political project, but a personal project for supremacy and celebrity. Most leaders at least claim to be servants of ideas and causes, whereas he grabs contrasting ideas and causes as if choosing vegetables for a ratatouille: “I haven’t got any political opinions,” he told a friend when seeking to become an MP. All that matters is that the colours are bright, and that the chef is glorified.

Even Brexit, perhaps his one enduring legacy, turned on naked self-advancement. My last one-to-one meeting with him, on 3rd February 2016, notionally to discuss Crossrail with London’s still-mayor, soon turned into an agonised discussion of political options. It was moments after he had left the House of Commons chamber, where he had offered a fence-sitting response to Cameron’s statement of his EU renegotiation terms and the setting of the referendum date for 23rd June. Pacing around his office, hand ruffling hair, he told me that he was “buggered” if he knew which side to take.

“Isn’t the right thing to say that it’s high time we started to lead in Europe, as your hero Churchill would have led?” I said. “Yes, well no,” he stammered. “That means Cameron leading, and that won’t work.” Wouldn’t work for himself, I think he meant, rather than for the country. He also trialled on me a populist riff on “shaking these grand corporate and diplomatic panjandrums out of their complacency”—a dress rehearsal for the “fuck business” of 2018 when the CBI pressed to stay in Margaret Thatcher’s EU single market.

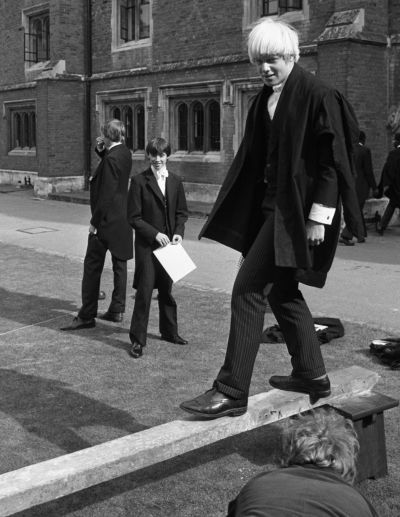

Trump is often cited as a populist parallel, but Boris pulled off his coup in a parliamentary system where it is virtually impossible to win from the outside. He triumphed because he is modern England’s supreme insider and seeming outsider at the same time. Electorally, he was the first politician to carry a UK-wide referendum against a prime minister, reaching downtrodden parts no other modern Conservative politician has reached. Bolsover, Bassetlaw and Blyth Valley are all Boris blue, as now is Hartlepool, a rare and remarkable government by-election gain this May, won by running as an insurgent in power. But socially and psychologically, he imbibed and exudes Etonian elitism to an extreme degree, emerging from the school in Thatcher’s decade of widening inequality, part of the vanguard of a new generation of Etonians asserting a right to rule and dominate. An extrovert by nature, he built himself a disarmingly popular, seemingly apolitical one-man band on these Etonian foundations, a sort of Bertie Wooster meets Henry VIII, bumbling and disarming yet cunning, ruthless and lethal.

Back in the late 1970s, when Boris started at the school, many thought there would never be another Etonian in No 10. Thatcher’s meritocratic Tories were thought to be too canny for that, learning from Alec Douglas-Home’s defeat in 1964 by Harold Wilson, a lower-middle-class Yorkshire grammar school boy.

Douglas-Home made a good joke in reply to Wilson’s jibe about being a 14th Earl—“I suppose when you think about it Mr Wilson is the 14th Mr Wilson”—but he still lost, and was rapidly replaced by a Tory middle-class grammar school boy, Ted Heath, who in turn was succeeded by the most famous bourgeois grammar school girl in history. The coup de grâce, so it seemed, was the Tory leadership election after Thatcher’s defenestration in 1990. John Major, a Brixton grammar school boy who hadn’t even gone to university, aced it over both Michael Heseltine (Shrewsbury and Oxford) and Douglas Hurd (Eton and Cambridge). His three successors as Conservative leader—William Hague, Iain Duncan Smith and Michael Howard—all attended state schools of different types.

When the Tories elected David Cameron as leader in 2005—overtaking the favourite, another grammar school boy, David Davis—I thought Eton might be his undoing. He half-suspected so too, hence the scramble to buy the copyright of the famous Bullingdon club photos of him with privileged friends in Etonian-style evening dress, and the intimations that the little Camerons would be sent to state schools. (His son was quietly put down for an Eton feeder prep school shortly before his father left Downing Street.) Gordon Brown’s government, two years later, is the only government in British history not to have contained a single Etonian.

But then history slammed into reverse. In 2010 Cameron squeezed into No 10, courtesy of the Lib Dem leader Nick Clegg (Westminster School and Cambridge, portrayed in Peter Brookes’s cartoons in the Times as Cameron’s Eton fag). Then, after the Theresa May interim in which he loomed large, Boris. Floreat Etona (“May Eton Flourish”) turned out to be more a command than a motto. And if there were to be a vacancy at No 10 any time soon, Rishi Sunak (Winchester and Oxford) only looks downmarket to, well, an Etonian.

“Gordon Brown’s government is the only one in British history not to have contained a single Etonian”

So what happened? The story of Johnson and Cameron is also the story of the resurgence of Eton, not only as a school but as a caste of unrivalled wealth of prestige. Eton endowed both men not only with the will to power but the means to conquer it, even to compete for it between themselves as if No 10 were an Eton prize.

Poring over the data, I now realise that even in the supposedly meritocratic 1980s, Etonians never left the Tory high command. They just didn’t, for a while, become leader. Even as their demise was supposed, 61 Etonians served as ministers over the Thatcher and Major years, about the same number as under the string of Etonian prime ministers (Eden, Macmillan, Douglas-Home) in the 1950s and early 1960s. And under the cover of Major, who said his mission was to create a “classless society,” fully 10 per cent of Conservative MPs in the 1992 parliament were Old Etonians.

“Thatcher didn’t mind toffs as long as they did not attempt to patronise her,” says William Waldegrave, Etonian younger son of the 12th Earl Waldegrave and a minister for almost the entirety of the Thatcher-Major era. Waldegrave is now provost of Eton—a post unique to that school, a kind of full-time “chancellor” with a palatial residence in its medieval quad, where he gives dinners to students, tutors and distinguished guests, like the head of an Oxford college. His recent memoir frankly parades the fact that, like Boris, “ever since I could remember, one consciously constructed goal [to become prime minister] had been the magnetic pole around which everything I did was centred.”

In the Labour-dominated 1960s and 70s, Eton’s leadership saw the meritocratic threat clearly. So having been for centuries essentially a comprehensive for the aristocracy, Eton changed into an oligarchical grammar school. With the incomes of the super-rich racing ahead, especially after Thatcher’s tax cuts for the wealthy and “big bang” deregulation of the City, the sky was the limit for both fees and resources. By the 1980s most boys were getting top A-level grades, a quarter of the teachers had PhDs and the facilities were world class.

Just as Eton and the other top public schools were mutating into warped meritocracies, the grammar schools were abolished, so the competition largely left the field. It was strangely unrealised by Labour politicians of the era that the esprit de corps and academic prowess of the grammar schools had been vital to the left’s ability to take on the Tory public school elite on equal terms. The main political casualty of Labour’s comprehensivisation of education turned out to be the Labour Party itself, which thereafter lacked leaders with the confidence to match the gilded grammar school generation of Wilson, Healey and Jenkins, while the new breed of “meritocratic” Etonians and fellow public school boys—girls were still rare, and girl Etonians non-existent—remained deep blue.

Ironically, or maybe logically, Labour’s only successful leader after Wilson came from Fettes, a public school dubbed “the Eton of Scotland,” although far less rich and establishment. Tony Blair’s headmaster there was Eric Anderson, who went on to become the modernising headmaster of… yes, Eton. Unsuspectingly, Blair legitimised the rehabilitation of Tory public school leaders, and Eton promptly reverted to type in providing Cameron and Johnson as successors to its 18 prime ministers since the very first, Robert Walpole, in 1721. That total of 20 Etonian PMs is more than one in every three of the total of 55, compared to one Etonian every 30,000-odd years if prime ministers were randomly drawn from across all UK secondary schools.

And so “the age of earnestness began,” wrote Anderson in his history of the school. Actually, it wasn’t that earnest, more a case of some things changing so that most things could stay the same. Under this more exam-driven regime, a few sons of Etonians had to slum it in lesser public schools. But feeder prep schools like Boris’s Ashdown House in Sussex raised their game and for those who got in to Eton, which included most of the type who would have gone to the school previously, the social ethos scarcely changed. “One retiring bursar,” Anderson recalled, “compared his job with running a resort town with 25 small hotels and a university campus.” In one respect the resort became grander still: Princes William and Harry donned Etonian tailcoats in the 1990s, the first royal heirs to do so. Anderson, who died last year, summed up his mission for Eton—“on the road from Windsor to Westminster”—in a phrase that could have applied in any of the last five centuries: “the habitual vision of greatness.”

Like a Zoom backdrop, this resurgent Eton is inseparable from Boris. While not from pure aristocracy or plutocracy, he is a classic Eton type: a bright boy from a thrusting Tory family—father Stanley a minor public school (Sherborne) Tory MEP of exotic international pedigree, whose grandfather was the last sultan of Turkey’s interior minister; mother Charlotte the artist daughter of a president of the European Commission of Human Rights—entering Eton from a top prep school by way of one of the 70 King’s scholarships which date back to the school’s foundation by Henry VI in 1440. It was an ascent analogous to that of Hurd, Thatcher’s last foreign secretary, who like Boris became Eton’s captain of school (head boy) and was a notable booster for Johnson during his rise, comparing him flatteringly to Disraeli as a Tory romantic touched by genius.

Such patronage helps explain why Boris, like generations of Etonians before him, gravitated naturally to political leadership. It is wrong to consider him a journalist who went late into politics. He first tried to become a Tory MEP at the age of just 29, in the footsteps of his father and personally encouraged by Hurd. Then, alongside Cameron, he tried to enter the Commons in 1997, at 32. They both lost in the first Blair landslide but landed rock-solid Tory seats in the following 2001 election. Boris’s was Henley-on-Thames, 15 miles upriver from Eton; Cameron’s was a bit further into Oxfordshire—Hurd’s old seat of Witney. By now, after a decade at the Telegraph demonising Brussels while honing an Etonian clown act on television, Johnson was continuing in this vein as editor of the high Tory Spectator magazine. The point is, journalism and politics were the same activity, both geared to becoming a Tory celebrity and then leader.

It is moot how far Boris was created, and how far curated, by Eton. Either way, the outsized egotist, with a “vision of greatness” anchored in the Greeks and Romans, was fully formed by the time he left for a gap year working at the private Geelong Grammar School—“Australia’s Eton” which, as his most insightful biographer Sonia Purnell puts it in Just Boris: The Irresistible Rise of a Political Celebrity, was “another demonstration of the Johnsonian fondness for the wealthiest and best (no sign of building latrines for starving Africans).” From there it was Balliol College, where he was one of about 150 Etonians at Oxford in the mid-1980s.

“Boris’s sheer chutzpah is potent because of Eton—the institution is not just a school for boys, it is a freemasonry for life”

The school report written by Boris’s Eton housemaster is often cited, denigrating his “disgracefully cavalier attitude to his classical studies… Boris sometimes seems affronted when criticised for what amounts to a gross failure of responsibility (and surprised at the same time that he was not appointed captain of school for next half): I think he honestly believes that it is churlish of us not to regard him as an exception, one who should be free of the network of obligation which binds everyone else.” The same could be said of every phase and every job in his life, again in his father’s footsteps.

However, the striking thing is that Boris did become captain of school, at the second attempt. He has a knack of winning top positions at the second try, including the premiership, precisely because he believes it churlish not to regard him as an exception. The caricatures of him as lazy are themselves lazy. Certainly, he disdains detail that doesn’t impinge on his interests, yet he is assiduous at both his vocation and his pleasures. He divides his efforts between them about equally when on a roll, but on the rebound from failure his work ethic is ferocious and focused. (In both respects he reminds me of Roy Jenkins.) Far more significant than a report for parental eyes is what Eton said about him publicly. When asked by journalist Anthony Howard—a friend of Stanley’s—who was the most interesting student of his time, headmaster Anderson replied: “Without a doubt, Boris Johnson… Anyone who’s spent an hour with Boris never forgets it. All I have to say to you about him is positive.”

Another reason Boris is so good at winning second time around, as he is doing now in reinventing his premiership post-Cummings, is that his obligation to people and policies is so weak. This too started young. At Oxford, when he first ran to be president of the Oxford Union, he was outsmarted by a Liberal grammar school boy who ran an anti-toff campaign and won a mass of Liberal-SDP votes. The centrist parties were riding high in mid-1980s Oxford, and unlike Labour students they didn’t boycott the Union on social grounds. Boris’s response? To run a second time allied with the SDP student faction, claiming to be a supporter and speaking passionately in a debate the night before the vote on the motion: “This House has had enough of two-party politics.” “I never realised until then just how intensely focused and determined he was,” said his opponent. “Sure he’s engaging, but this guy is an absolute fucking killer.” Cummings should have checked his form.

Boris’s sheer chutzpah is as potent as it is because of Eton—the institution is not just a school for boys, it is a freemasonry for life. Cameron’s break into politics started with a mysterious call from Buckingham Palace to Conservative central office suggesting this was a “remarkable” young man to watch. In Johnson’s case, Hurd and Anderson’s leg-up was only the first instalment, and throughout his career the help was extended—and continues to extend—from the wider establishment, itself still mostly public school and Oxbridge. The importance of this top public school freemasonry struck me while watching Cummings’s six-hour, search-and-destroy mission against his former boss before a parliamentary committee in May. His dire imprecations reminded me of a similarly Baroque denunciation by Max Hastings in July 2019 in the Guardian, on the eve of Boris’s triumphal entry into No 10. Re-reading Hastings, I recalled with a start that the key figure identified by Purnell as launching Johnson’s career and fostering the whole incarnation of today’s “Boris” is… the same Max Hastings who was here describing his one-time protégé as “a cavorting charlatan” exhibiting “moral bankruptcy rooted in a contempt for truth,” caring “for nothing but his own fame and gratification.”

“I have known Johnson since the 1980s, when I edited the Daily Telegraph and he was our flamboyant Brussels correspondent,” wrote Hastings, launching his ineffectual thunderbolts. After reading this sentence twice, I referred back to Purnell’s book, and realised that Hastings (Charterhouse and Oxford) didn’t just know Johnson in the 1980s, he appointed him as his paper’s “flamboyant Brussels correspondent,” where Boris made his name and brand by flamboyantly inventing stories about EU plans to ban bent bananas, standardise condoms and achieve federal domination.

Moreover, Hastings didn’t just send Johnson to Brussels, he recruited him for the Telegraph days after he had been sacked by the Times for making up quotes. Although as a graduate Johnson had lasted only a week in management consultancy, he had soon—through family connections—landed a coveted traineeship at the Times before spectacularly blowing this chance. Then Hastings, who had met Johnson when speaking at the Oxford Union, rode to the rescue. “Without Hastings’ patronage,” Purnell writes, “it is quite possible that Boris would have been lost forever to journalism.”

If Johnson’s ethics, which Hastings now deplores, weren’t sufficiently apparent at the start, they were soon made crystal clear to him. We know this because Purnell documents that he was sent personally—and anonymously—the notorious tape of the phone conversation in which Boris and his Etonian friend Darius Guppy discuss hiring a heavy to “beat up” a journalist who had crossed Guppy’s path. “Ok, Darry, I said I’ll do it and I’ll do it. Don’t worry,” says today’s prime minister.

What happened next—before “Darry” went to jail for fraud, that is? “Hastings’s response was to fly Boris back to London for a serious discussion,” writes Purnell. “Anyone might have expected a dramatic showdown and even a resignation or a sacking at the end of it.” But by Hastings’s own account, the “interrogation” brought out “all Boris’s self-parodying skills as a waffler. Words stumbled forth: loyalty… never intended… old friend… took no action… misunderstanding. We dispatched him back to Brussels with a rebuke.” “And so Bumbling Boris won the day,” Purnell relates.

Again, there is no making sense of this great escape without understanding Etonian presumption. James Wood, a literary critic who was in Cameron’s year, writes of “the Etonian’s uncanny ability to soften entitlement with charm.” He recalls: “we were told to be wary of misusing our superiority, but we were not told we didn’t have it.” The sheer entitlement is what amazes.

A recent memoir by Musa Okwonga, Ugandan-British son of doctors and rare black Etonian, who is a novelist in the school’s alienated counter-cultural tradition (think George Orwell), sheds some light: “I ask myself whether this was my school’s ethos: to win at all costs; to be reckless, at best, and brutal, at worst. I look at its motto again—‘May Eton Flourish’—and I think, yes, many of our politicians have flourished, but to the vast detriment of others. Maybe we were raised to be the bad guys.” In a telling riposte from the citadel, Etonian Tory MP Bim Afolami, reviewing Okwonga, blithely dismisses its discussion of politics as “the weakest part of the book.” Eton’s genius lies, rather, in giving politicians like Afolami “a huge appetite for hard work and a fierce competitive streak,” plus a pure “belief in the importance of public service.”

Being Tory, and a resolute if genteel defender of elitism, is almost invariably part of this “belief in public service.” As Tony Blair’s schools minister I was once invited to discuss education at Eton’s political society. “Sir, the headmaster said you’re not one of those really red ones who wants to abolish us,” began the first questioner, to titters. “But you do realise that if you tried, we would be very angry, because we are really good for the country.”

For the recanting Hastings read also the destroyed Cameron, who gave Boris his break to run for mayor of London in 2008 then tolerated his leadership of the Leave campaign in 2016, and the ejected Cummings, mastermind of Leave and Boris’s takeover of No 10. Boris is “a pundit who stumbled into politics,” began a recent Cummings philippic against his own creation. If he believes that, then rarely has one public schoolboy so misjudged another. Johnson is a literal class act.

Now that Brexit is “done” and the pandemic muddled through, where does the Prime Etonian go next?

Unlike post-Falklands Thatcher and pre-Iraq Blair, post-vaccine Johnson apparently has little he wants to accomplish with his immense stock of power—beyond keeping the celebrity show on the road, and striking Churchillian poses. “The fatal thing is boredom. So I try to have as much on my plate as possible,” is the most insightful line by him I have found, in a 2002 Times “A life in the day” column.

The best line about him is by a critic quoted by Purnell: “like Lord Palmerston, Boris does not have friends, merely interests.” Interests need sedulous cultivation, more so in many ways than friends, and he is devoting the full resources of the honours system, public appointments, the planning system and a good deal of public policy to the task.

What of his plan for the country? Union Jacks with everything is the main discernible theme. In place of strategy, we have a handful of populist catchphrases—“Global Britain,” “levelling up,” “war on woke.” Typical of the paltry resulting policy is the much-vaunted Australia trade deal, which offsets Brexit trade losses in Europe with an increase in national income of perhaps 0.02 per cent. It’s part of a “tilt towards the Indo-Pacific,” which also includes the despatch of the Royal Navy’s new aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth to cruise around the Indian Ocean for no essential purpose. As for “flagship” legislation, parliament is engaged with trivialities like the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Bill for free speech tsars on university campuses, hiding the absence of substance by stoking a culture war vigorously supported by the new Fox News lookalike GB News.

To observers of his London mayoralty, the lack of interest in social policy is no surprise—witness his neglect of affordable housing, perhaps the most pressing issue in the crowded and extortionately expensive capital. However, in my experience, Boris does believe in one thing: grands projets with his name emblazoned. He doesn’t much mind what the projets are, but the grander the better. As mayor of London, as well as a double-decker bus and bike hire scheme named after himself, his biggest projects, in tandem with the Blair-Brown government, were the London Olympics and Crossrail, the £16bn east-west London commuter line. At the launch of the Crossrail construction at Canary Wharf he quoted Juvenal to me in Latin. I can only remember the English: “Give them bread and circuses and they will never revolt.”

One of the few politicians Boris consciously imitates is Michael Heseltine, maybe the best modern prime minister we never had. “Canary Wharf—Hezzagrad, as people call the great city that has arisen in Docklands—is thanks to his energy and drive,” he said admiringly in his maiden speech as an MP.

But there is a key difference with Hezza. “Bozza” isn’t unduly fussed if his projects don’t end up happening—“Boris Island” airport, a mooted bridge to France and the garden bridge across the Thames—so long as they get people talking. About to join the list is his huge bridge or tunnel across the Irish Sea, a wacky idea to maintain the Union with Northern Ireland, which the Treasury and transport officials are quietly killing off. But if there is a big infrastructure scheme that’s ready to go, he would generally rather make it happen than not. Tellingly, the one major issue on which he overruled Cummings last year was HS2, the £100bn high-speed line from London to Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds. There are now 250 construction sites on the route through the Chilterns.

“Post-vaccine Johnson apparently has little he wants to accomplish with his immense stock of power”

It is often said that Boris is a big spender and that battles with Rishi Sunak will loom large post-Brexit. I’m not so sure. While Boris likes certain grands projets, and bungs for whatever he judges electorally vital, beyond that he is a small state, low-tax Tory by Etonian pedigree—especially when it comes to the rich. In response to George Osborne’s “omnishambles” 2012 budget, he argued the chancellor should have cut the top rate of tax even more deeply. Social justice is one of his supreme unconcerns. His Telegraph column defending “sickeningly rich people” on the grounds that “if British history had not allowed outrageous financial rewards for a few top people, there would be no Chatsworth, no Longleat,” comes straight from the Etonian heart. So too does the one that began: “Cancel the guilt trip. Africa is a mess… but it is not a blot on our conscience. The problem is not that we were once in charge, but that we are not in charge any more.” The big cuts in overseas aid were prompted, not opposed, by No 10.

I suspect post-pandemic Boris will be largely politics by populist gesture, some costly but most costless. No previous government has spent so much on opinion surveying, as the prime ministerial WhatsApp messages released by Cummings attest. In the grim depths of the first lockdown, Boris asked his strategist whether something unspecified was “from tonight’s focus group and polls?” Cummings responded: “it was from a whole run of them.”

A minister tells me that the first thing Boris looks at each morning is the latest private polls. He allowed Sunak to veto the £15bn education catch-up plan this summer, despite having pledged support to his own education recovery commissioner Kevan Collins, because private polling showed a longer school day—a key part of the plan—to be unpopular, particularly with working-class parents in the “red wall.” “Why battle with Rishi for billions for stuff which might be good for the punters but which they don’t even want?” one No 10 pollster told me. Overseas aid is equally unpopular—and therefore dispensable by a prime minister who doesn’t give a fig.

However, much still depends on who “runs” Boris after Covid. When he was mayor of London, consiglieri emerged after initial turbulence: Simon Milton and Edward Lister, Tory ex-leaders of Westminster and Wandsworth councils, filled the role successively at City Hall. The Cummings mayhem in No 10 had method as well as madness: only by shock and awe was it possible to get Brexit “done,” his administration having taken over in July 2019 with no parliamentary majority and a large Remain group of Tory MPs, some inching towards supporting a second referendum. But with Brexit done, the chief strategist was also done.

So far, no post-Cummings consigliere has emerged. No 10 is a court of jostling factions, including rival ministers (Sunak vs Raab vs Gove), rival advisers (Treasury civil servant Dan Rosenfield vs civil service-haranguing adviser Simone Finn), and inexperienced Cabinet secretary Simon Case. The strongest emergent figure is Boris’s new 33-year-old wife Carrie Johnson, a former party press officer, whose father Matthew Symonds is a biographer and friend of American tech billionaire Larry Ellison (net worth reported as $92bn)and was director of Ellison’s charitable foundation before it was shut down last year. “The strongest feature of Carrie by far is her fierce intent to keep him in No 10,” says a friend. Apart from a tribal conservatism and a millennial passion for animal rights, she comes with no pre-determined agenda beyond Boris’s quest for fame and fortune.

Eventually, an opposition leader will get the measure of Boris, or a corner will be simply too tight. But he is still on the up, and he has the great institutions at his beck and call. He even got the Catholic church to marry him for the third time, thanks to a loophole by which the Vatican does not recognise his earlier non-Catholic marriages—a supremely ironic and characteristically Johnsonian manipulation of a venerable institution older than Eton College. As he put it in his maiden speech as an MP, in perhaps the only pure statement of his political philosophy: “there is a hidden wisdom in old ways of doing things.”