Let’s accept that someone at the BBC made a clumsy error in editing some clips of Donald Trump addressing the crowd on January 6th 2021. And let’s acknowledge that the BBC has known for some time that there have been problems with aspects of its Arabic service. Worst-kept secret in the world: all media organisations occasionally screw up.

That’s true of all Fleet Street newspapers, as well as leading broadcasters. Journalism, as the wise old Washington sage David Broder once wrote, is “a partial, hasty, incomplete, inevitably somewhat flawed and inaccurate rendering of some of the things we have heard about in the past 24 hours—distorted, despite our best efforts to eliminate gross bias—by the very process of compression that makes it possible for you to lift it from the doorstep and read it in about an hour.”

The veteran Pulitzer prize-winning columnist was writing about newspapers, but the same is true of every digital outlet and television company. The important thing, as Broder went on to add, is that we label the product accurately—and correct and update any errors.

The Daily Telegraph is no more immune to making mistakes than any other news outlet. The difference is that, when their own editorial, ownership and ethical failings come to light, it doesn’t register nine on the Richter scale of public and political outrage. That’s reserved for the BBC.

Fair enough, you might say. We all contribute to the BBC’s journalism through the licence fee, and it enjoys a somewhat protected status within the UK’s media environment. All true. But the venom spat at the BBC on a near-daily basis by its ideological and commercial enemies is out of all proportion to its occasional lapses.

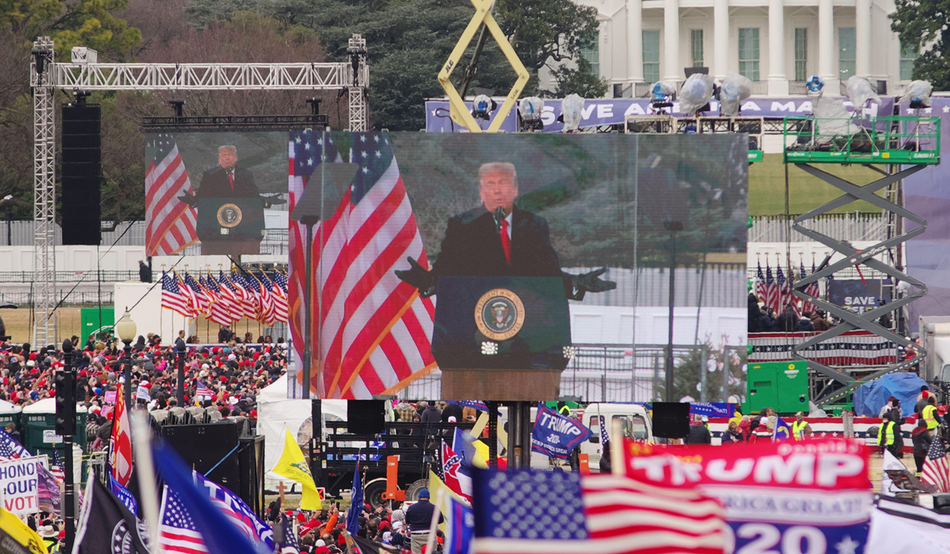

The latest squall has arisen over a “dossier” apparently compiled by one Michael Prescott, a former journalist working for Rupert Murdoch, who had something of a ringside seat at the BBC for three years. He has questioned the editing of a Panorama programme on Donald Trump—which elides separate quotes to make it look like Trump said he would march on the Capitol and “fight like hell” alongside his supporters.

Prescott also has concerns about what he regards as an anti-Israeli bias within the corporation, as well as its coverage of certain trans issues.

Well, all those claims will doubtless be picked over in the coming weeks, with MPs demanding BBC bosses explain themselves. Two of Prescott’s complaints seem particularly questionable. The first is that the Panorama editing was “completely misleading.” Prescott argues that the fact that Trump did not explicitly exhort supporters to fight at the Capitol was one of the reasons he wasn’t prosecuted.

But the Congressional committee which examined the day’s events in detail recommended criminal charges on the basis that the former president did indeed incite the attack on Congress—a verdict backed by the only federal district judge to consider the case. The Senate voted 57-43 to impeach him, with seven republicans backing the motion. So, while the way the film was edited was wrong, it’s not clear that it was “misleading” in the way Prescott argues.

Secondly, Prescott seems to have believed that an “equally aggressive” look at Kamala Harris should have been commissioned. He found it “shocking and alarming” the aberrant behaviour of Trump should be singled out for especial scrutiny. But that suggests a bizarre notion of editorial equivalence. The deputy head of news, Jonathan Munro, was surely right to have dismissed Prescott’s idea of “due impartiality.”

Similarly, with criticisms of the BBC and Israel, there have been plausible and detailed critiques which suggest that the BBC is, contrary to Prescott’s own belief, actually biased in favour of Israel. But such analyses tend to sink without trace. Is this, in itself, a form of bias?

But let’s take a step back and look at the decidedly odd governance arrangements at the BBC, which is still, despite all of the above, one of the greatest news organisations in the world and quite easily the most trusted news providers in the UK.

Prescott is reported to have sent his dossier to BBC Board members. They are a motley bunch, with five of them (including the chair, Samir Shah) appointed by the government of the day. The 13-strong board include several business leaders, lawyers and people with experience in investment banking and private equity. I counted three (not including the director general, Tim Davie) with any substantial record in journalism.

But the key committee looking after editorial standards is an even odder body since it comprises three insiders (Shah, Davie and head of news Deborah Turness) as well as two outsiders, Sir Robbie Gibb and a former BBC COO, Caroline Thomson.

It’s odd, because it’s an uncomfortable mix of the people supposedly enforcing standards and those who are accused of allowing standards to slip. This is the body which, according to Prescott, didn’t take his concerns seriously enough. Prescott was, along with one Caroline Daniel, an editorial advisor to the committee.

Here’s where it all becomes a little murky. Robbie Gibb will be familiar to some as a rather abrasive “proper Thatcherite conservative” (his own description) who led the mystery consortium to buy the Jewish Chronicle on behalf of a secret backer whose identity has never been revealed. His stewardship of that paper saw it mired in a number of its own ethical and editorial failings. Pots and kettles.

Whatever you might say of Gibb, he does not pretend to be impartial on issues related to British politics or Israel. But he was appointed by Boris Johnson and confirmed by Rishi Sunak, so the BBC is stuck with him as a supposedly objective arbiter on such matters.

Prescott is reported by the Financial Times to be a friend of Sir Robbie. There was some controversy over Johnson’s choice of him to help select the chair of OfCom, which regulates the BBC. That process—widely regarded as farcical—resulted in Lord [Michael] Grade, 82, eventually getting the job after Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre was deemed unappointable. It was claimed, and never denied, that Gibb had intervened to try and ensure that a long-standing Conservative back office functionary landed the role instead.

But there is a more serious oddity here. Eight years ago, Gibb decided he was done with journalism and embarked on a life of public relations—first in Downing Street for Theresa May, and then with a “Global strategic Communications firm”, Kekst CNC.

Prescott’s career took a similar path. Twenty-four years ago, he bailed out of journalism—again preferring to join the ranks of PR professionals. For eight and a half years, he worked for Weber Shandwick. There followed nearly 16 years spinning on behalf of BT. For the last nine years he has worked for Hanover Communications, a PR company with links to the Conservative party.

And Ms Daniel? By remarkable coincidence she, too, decided that journalism was no longer for her. Nine years ago, she quit her job at the FT and joined Brunswick, where she provides “strategic communications advice.” That leaves Caroline Thomson, who had a solid track record in journalism up to 2000 before looking after the corporation’s operations and, subsequently, a portfolio life with various public sector bodies.

If I were a BBC journalist, under such intensive scrutiny and fire, I’m not sure I would be terribly comforted by these governance arrangements, beginning with a Director General with no substantive journalistic record and a Board with negligible experience of what it is to be a journalist in the 21st century.

On top of that, I’d wonder why such close editorial scrutiny should have been entrusted to three key people who themselves rejected journalism in order to enjoy lucrative careers in corporate and political communications. Who, bluntly, would you trust more to be impartial on the Middle East—Robbie Gibb, Michael Prescott or Lyse Doucet? Why should the PR professionals who turned their own backs on journalism sit in judgment on the latter?

By all means, let’s have a debate about Prescott’s “dossier”, preferably unfiltered by the Daily Telegraph. But let’s keep a sense of proportion about it all. And let’s find a governance structure for the BBC that equips it to handle complex editorial decisions robustly and expertly. The BBC is in a mess—but not necessarily the mess you think.