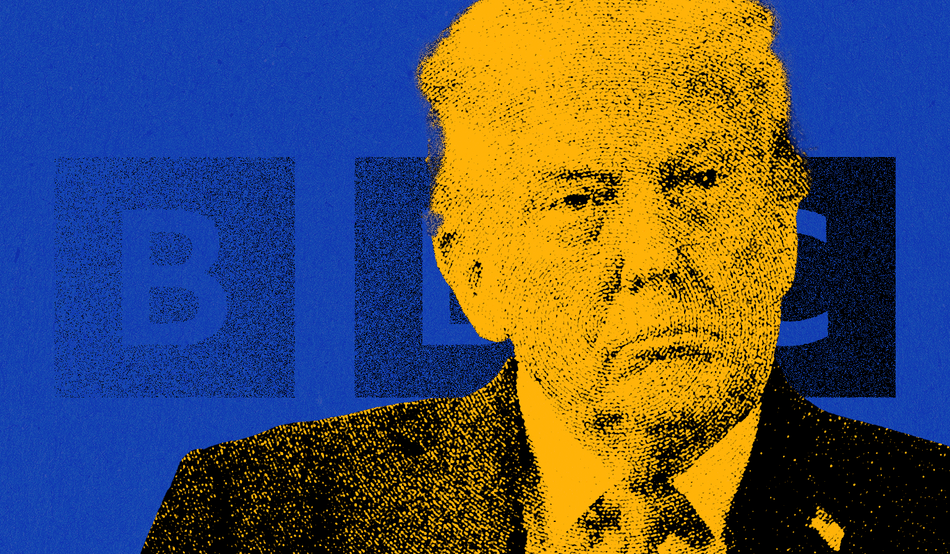

So, Donald Trump’s Big Beautiful BBC writ has finally arrived, and it does not disappoint. We are invited to believe that the US president is a man of almost saintly virtue whose unblemished reputation—and business prospects—have been irreparably tarnished by one lousy Panorama programme.

Trump asserts that the BBC had the “express intent of interfering with [the 2024 presidential election] and trying to undermine President Trump’s odds of winning re-election”. He wants “compensatory and punitive damages” of no less than $5bn and, depending on how you read his claim, as much as $10bn.

Some twerps on the right of British politics, so blinded by their hatred of our national broadcaster, have piped up in support. Rupert Lowe MP, a former Reform member, tweeted “Trump is suing the BBC. Good luck to him, I say.”

The writ refers to the outgoing director general Tim Davie as “disgraced” and quotes with some glee the opinion of the former BBC editorial adviser, corporate PR man Michael Prescott, that the programme was “neither balanced nor impartial—it seemed to be taking a distinctly anti-Trump stance”.

So, well done, whoever chose to leak Mr Prescott’s memo to the Daily Telegraph. In addition to toppling a respected DG and causing institutional meltdown at the BBC, you’ve also landed the corporation with the enormous expense of defending a specious defamation action.

I look forward to Mr Prescott being called as a witness on behalf of Trump—a habitual liar and incorrigible denigrator of truthful media as “fake news”. The squirming will be exquisite.

In Trump’s first year we have seen a tsunami of cowardice in which previously grand institutions—including the media, law and academia—have cravenly bent the knee, as though the 47th president were some kind of medieval monarch.

The BBC has no choice but to defend this preposterous claim. The corporation is not a subject in the quasi-feudal estate of Trump’s fantasies. Unlike the institutions which have crumbled, it is not reliant on favours from the ruler and his unlovely cronies.

And, in any case, the law is on its side.

Let me let you into a secret: journalists make mistakes. The Daily Telegraph makes mistakes: I will not embarrass it by listing some of the more egregious ones. The Guardian certainly made mistakes under my editorship. The Sunday Times, when Prescott was working there [he was political editor between 1991 and 2001], was singled out in 2000 for its ethical failings by Roy Greenslade, then a media commentator for the Guardian and subsequently a professor at City University.

“I’ve received more unsolicited complaints about the Sunday Times than any other paper,” he wrote in July that year, citing “many... instances of alleged inaccuracy, distortion and misrepresentation.”

He continued: “The Sunday Times appears to have lost its credibility among the nation’s opinion-formers... According to the host of complainants I have spoken to, the paper is reluctant to admit any wrongdoing.”

I should emphasise that Greenslade did not single out Prescott for any criticism, but the point stands: that even the most august news organisations are fallible. And that journalists making mistakes and not promptly correcting them is not necessarily a sign of malice or institutional bias.

By way of illustration, this week I attended a showing of Cover-Up, a film profiling one of the most distinguished reporters of our age, Seymour Hersh. It’s set for release on Netflix on 26th December, and is well worth a watch.

Hersh, now 88, broke some of the most impactful stories of his generation, from My Lai to Abu Ghraib, via Watergate and Vietnam. Over nearly six decades he exposed brutality, deception, torture, illegal surveillance and much else. His work makes an inspiring case for public interest journalism.

But he has also made some howlers along the way. He fell for forged documents over JF Kennedy, and his reliance on unnamed sources led to—how can one put it kindly?—vigorously contested responses around Syria, the death of Osama bin Laden and who bore responsibility for the sabotage of the Nord Sea pipeline. “If I ever made the claim to be perfect, I now withdraw it,” he says on the film.

The BBC’s error in the Panorama film which has so upset Trump is footling stuff by comparison. Much of the film—contrary to the impression given by Mr Prescott—gives voice to Trump’s most passionate supporters. The disputed 20-second segment of a 55-minute programme would have caused little comment if the director had inserted a white flash to indicate that two separate sentences in Trump’s speech on 6th January 2021 had been joined together in the edit suite.

A rather more distinguished journalist than Mr Prescott, the former New York Times executive editor Bill Keller, commented of the mistake: “It was an unnecessary own goal. By focusing on an ethical misdemeanour, the debate overlooks the indisputable reality that Trump inspired, energised and then celebrated a violent attempt to thwart an election.”

But this is where the BBC—assuming it holds its nerve—should find American law is on its side. In 1964, around the time Hersh began uncovering the Pentagon’s dirty laundry, the US Supreme Court came out with a unanimous ringing First Amendment judgment which enshrined two important principles.

It held that, absent any evidence of “actual malice”, journalists should have an extraordinary degree of protection in attacking or criticising public officials—and there is no more important public official in the world than the US president.

Second, it held that making honest mistakes shouldn’t count as undermining the shield that journalists needed if they were to do their job of holding prominent people in public life to account. It found “that erroneous statement is inevitable in free debate, and that it must be protected if the freedoms of expression are to have the 'breathing space' that they need ... to survive”.

Justice Brennan channelled the British political philosopher John Stuart Mill in pronouncing: "Even a false statement may be deemed to make a valuable contribution to public debate, since it brings about 'the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.’”

On the award of libel damages the court was equally firm, speaking of how the fear of the expense involved would chill journalism: “The pall of fear and timidity imposed upon those who would give voice to public criticism is an atmosphere in which the First Amendment freedoms cannot survive."

At least one of the judges, Justice Black, advocated even greater protection, arguing for an “unconditional right to say what one pleases about public affairs”. He wanted “absolute immunity” for anyone criticising public officials. A supposed free speech absolutist such as Elon Musk would surely approve.

The Trump administration talks a good game on free speech, extolling America as one of the last remaining countries in the world where free expression is the bedrock of democracy. It has recently pronounced that Europe faces “civilisational erasure” as it curbs political liberties and freedom of expression.

How pleasingly ironic it would be for the British Broadcasting Corporation to remind Americans what the First Amendment is all about. The BBC may be about to lose a director general, but it still has a spine. I hope.