Here’s a lesser-known fact: over the past five years, every recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature has been recognised first by the Booker Prize or the International Booker Prize (IBP). Since the beginning of this century, a total of 12 writers who won or were shortlisted for either of the two Booker prizes have gone on to win the Nobel. Just last week, the Hungarian master-fabulist László Krasznahorkai became the latest Booker alumnus to be named Nobel laureate.

I have been the administrator of the IBP for two decades, and have probably sat in on 150 judging meetings over that period. When I read that Livres Hebdo, France’s answer to the Bookseller, called the Booker the “antechamber” of the Nobel, I was delighted—if not a bit surprised. And then I remembered a conversation a year ago with an editor at another industry mag, Publishers’ Weekly, who called me and said: “You’re the guys who do the Swedish Academy’s work for them!”

On the face of it, the Bookers and the Nobel could hardly be more different. The Nobel is awarded for a body of work; the two Booker prizes for single books. The original annual Booker award is for a novel written in English and published in the UK or Ireland in the previous year, while the International Booker is for a book translated into English (though it started out as a biannual award for a body of work). The Nobel judges, all members of the Swedish Academy, sit in on the judging panel year in and year out, whereas the Bookers appoint a completely new panel every year. Both Booker prizes publish a longlist of 12 or 13 books (the Booker dozen), followed by a shortlist of six. Precisely how the Nobel candidates are whittled down is anyone’s guess; bookmakers’ odds are often the only clue. There is no Nobel longlist or shortlist.

Beyond the differences between the Nobel and the Booker, though, are also notable similarities. These aren’t only about the reading—which is considerable—but also about the subsequent discussions that take place, as well as the judges’ engagement in the whole process.

Literary prizes tend to divide in two. The most common (and the worst paid) are those that operate a triage system for the submitted books, with each book being read by two judges who make a recommendation as to whether it goes any further. Limited emotional engagement, I have found, goes hand in hand with limited judges’ engagement.

Judges of the Nobel and the Booker on the other hand spend most of the year reading. Every judge reads every book. The Swedish academicians’ books are wrapped in brown paper so no-one on the subway, or in the Swedish archipelago through the summer, will know what they are reading. Booker judges often say afterwards that the discussions were even more interesting than the reading.

As a society, we like to think we discuss issues openly and with tolerance. But nothing puts that idea to the test like returning month after month to the same room with the same people to discuss the thorny issues that a book might give rise to, such as on race, history, politics or sex-based rights. There is no protection here for the worst judges, those guilty of being cloth-eared or close-minded. Even so, individual books affect people differently, and unanimous agreement from the outset is virtually non-existent. The best judges are those who can listen carefully to their fellows and are prepared to let another judge open their eyes—or even change their mind altogether.

Imagine the discussion about Krasznahorkai, whose two best known books, The Melancholy of Resistance (1989) and Seiobo There Below (2008), are famous for their very long and very brilliant sentences. How can he be funny if his writing is so bleak? Does he believe in God? When will the full stop ever come?

Some members of the Swedish and Norwegian Nobel committees (the Norwegian committee awards the peace prize) clearly think they are doing God’s work. If you have any doubt, listen to the chair responding to a reporter’s question about Donald Trump’s campaign to win the peace prize himself: “This committee sits in a room filled with the portraits of all the Nobel laureates. And this room is filled with both courage and integrity. We base our decision only on the work and the will of Alfred Nobel.” I’d wager that any Nobel committee would tell you the same thing.

In 2007, the Irish novelist and playwright Colm Tóibín said that Krasznahorkai was the single biggest discovery he’d made over two years reading as a judge for the Man Booker International Prize, as it was then called. But choosing a winner for the Nobel Prize in Literature has come to be about more than a quest for literary merit. It’s about vision, humour and courage, and about finding the giants who stand on the shoulders of the giants who went before them, the better for us to look up to them. Although the Nobel (and the Booker) have occasionally made mistakes, they aim mostly for the best of humanity.

For anyone who hasn’t the stomach for Krasznahorkai’s sinuous sentences, proof that the Hungarian author is adept not just at writing the truth but at speaking truth to power, as any Nobel laureate should, came in a tweet in response to a glowing message from the Hungarian prime minister, Viktor Orbán, who called him the “pride of Hungary”: “I thank [him] for his congratulations,“ he wrote. “But I will always oppose his political actions and ideas. I remain a free writer.” Whether it’s on social media or the page, Krasznahorkai is a classic Nobel laureate of our time.

What the Booker tells us about the Nobel

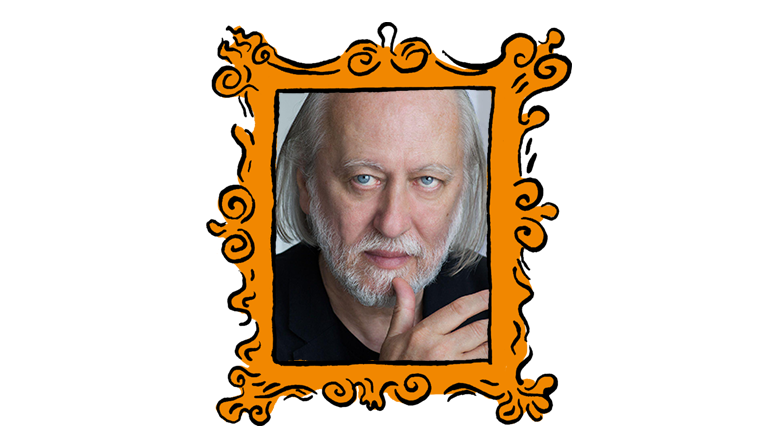

Some think László Krasznahorkai is a different kind of writer from previous laureates. But he does share one thing in common with many of them: he, too, is a Booker winner

October 16, 2025

Image: Sipa US / Alamy Live News