In 2024, Florida loosened its rules on teenagers working—clearing the way for youngsters to toil longer shifts, including at night, and allowing parents to waive a cap on term-time labour. In 2025, there was a serious push to go further, including by extending deregulation down the age range from 16 to some 14-year-olds. Draft laws progressed through legislative committees but ran out of procedural road. For now, then, the forward march of child labour has been halted in the US state. Will capitalism let things rest there? Or will the drive to accumulate and the need for cheap hands force the return of such, well, modest proposals?

Your answer will be shaped by your understanding of the economic system we live in, something Sven Beckert’s sweeping, 1,000-year history will do nothing to brighten. He conceives capitalism as a particular and unresting logic. It ducks, dives and twists with the times but can never relent in its animating mission: setting ever more people, land, machines and methods to work in pursuit of financial returns. There may be conditions where, say, child labour ceases to rank as a plausible avenue of profit; education might become overwhelmingly important for productivity, or realistic politics might simply preclude it. And such circumstances may have applied in the wealthy economies for the best part of 200 years. But for Beckert, at least as I read him, we can never rely on a capitalist society for moral restraint, should circumstances shift again.

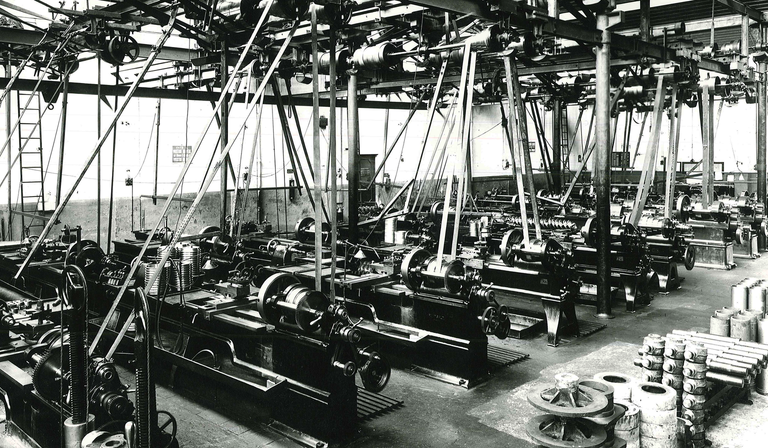

Despite its dark thesis, this is a book with a remarkable breadth of vision. Beckert dives down to describe, in close detail, the Fiat production line in 1920s Turin that was archetypal of industrial capitalism. He soars up to distil, in a few crisp pages, the interlocking crises of the world’s energy and monetary systems in the 1970s, which levered open the cracks through which capitalists escaped their postwar constraints. He charts the original advance of the culture of the bourgeoisie through the spread of opera houses, then tracks its evolving financial fortunes through dry statistical tables. He immerses us just as deeply in Chile and Senegal as Germany or the United States. And he takes us three-quarters of a millennium back before the first of those belching Lancastrian mills that the words “early capitalism” bring to mind, into the world of medieval Middle Eastern merchants, such as Ibn Awkal, whom Beckert regards as capitalism’s true pioneers.

As we reckon with the border-straddling corporations of disembodied, post-industrial capitalism, this forgotten—yet equally flighty—pre-industrial capitalism is plausibly worth a fresh look. And although Beckert’s dazzling array of material could easily lead to incoherence, it is, thankfully, marshalled in support of three clear purposes, relating to the geography, the chronology and the ideology of capitalism.

Geographically, Beckert’s contention is that capitalism was “born global”. Although he doesn’t quite spell it out, he seems to think of capitalists as people who not only hold wealth but hold it in forms that can in principle be redeployed towards new purposes or places. As those ancient Arab traders shipped indigo, brazilwood or spices between Aden, Cairo and Genoa, they not only accrued capital through arbitrage, but also slipped free of local restrictions on how their assets could be deployed.

Thus, even from the system’s modest beginnings on the margins of feudal societies, the coordinates of capitalism straddled the Earth. Indeed, in creating its early infrastructure, Europeans lagged behind. It was Sudanese and Japanese merchants who came up with bills of credit to allow trade to be carried on without risking precious metals on long voyages; Chinese traders who devised instruments to settle debts remotely; and early Islamic jurisprudence that facilitated contracting for pooled investments and limited liability partnerships. The east was frequently ahead in production, too. India’s cotton weavers could produce cloth of far higher quality than anything manufactured in Britain until well into the colonial era. All of this, Beckert nails.

His second big argument, concerning chronology, is that it was only after the discovery of the Americas and the creation of plantation economies that Europe became the engine of capitalism. An established authority on cotton and the role of slavery in US development, he foregrounds “the Atlantic complex” as “the beating heart” of the maturing system. Back in March 2024, I wrote in these pages about how slavery was more or less directly linked to every aspect of the British industrial revolution: technological, financial, commercial. Beckert widens that story to other European powers such as the Netherlands and France, providing new insight into exactly why the chains of the new world proved to be such a critical—and enduring—catalyst.

Capitalists had previously battled to lure rural cultivators, focused on their own subsistence, into producing for distant markets. But they were frequently thwarted by local nobles and the deep suspicions of peasants themselves. In newly discovered terrain, by contrast, aided by guns and pathogens, they could print their economic designs onto a blank sheet. With workers forcibly transported from disparate shores, there were no social traditions to stand in the way of these designs. Beckert neatly captures the monstrous cruelty of the plantations: “Sugar ate men.” What mattered for capitalism, though, was the sheer scale of the assets accumulated, and the exemplar of how merchants could remake the world.

Beckert neatly captures the monstrous cruelty of the plantations: ‘Sugar ate men’

Coercion became a shakier foundation stone of capitalist riches from the time of the 1791 slave rebellion in Saint-Domingue, the French colony that became modern-day Haiti, but neither abolition in the British Empire (1834) nor emancipation in the US (1863-65) came close to dislodging it. For one thing, chattel slaves continued to sweat on Brazilian plantations. More subtly, the newly “free labour” turned out to be anything but. With an 1848 House of Commons Select Committee lamenting that “no rates of wages” would induce Caribbeans in their “independent condition” to toil the hours planters needed, capitalists around the Atlantic desperately needed to innovate. Beckert’s eye-opening chapter on “reconstructing labour” documents the diversity of ways in which, with state support, they did so.

The new chains needed were often forged by travel debts and punishing repayment contracts. Consider John Gladstone, father of the great Liberal prime minister, a merchant who’d owned many slaves. He used his publicly funded compensation for their emancipation to transport indentured Indians to his plantations. French investors in notionally emancipated Réunion, a colony in the Indian Ocean, managed to criminalise workers who declined or “deserted” posts. For a time, they won the right to “liberate” locally enslaved East Africans by purchasing them and forcing them to sign long labour contracts. When that ploy faltered, they secured tens of thousands of Indians via a French treaty with Britain; one such worker is recorded as arriving to seek legal assistance “in an iron collar and chains… fastened by his employer”. Then Réunion’s capitalists turned to sourcing workers from Madagascar, who were subject to “beatings”, “brutality” and “physical abuse”, as documented in official reports written for Paris into the 1920s.

More widely, one of Beckert’s more arresting contentions is that for most human beings, through most of history, the idea of working full-time, not for their own provisions but for cash, was utterly alien: the proletariat almost always had to be forced into being. Sometimes this involved slavery or indentured labour, but just as often it was accomplished by undermining the traditional basis for subsistence production. By enclosing, for example, common lands in Georgian England, or indeed through more recent restrictions on access to the plains of Ethiopia or the forests of Indonesia.

Throughout, Beckert is painfully concerned to rescue all those press-ganged by capitalism from the condescension of posterity. On their behalf, he criticises Marx and Engels once each: Engels is chided for urging respectable labour leaders to keep clear of an unruly, ragged-trousered rabble; Marx for writing off the peasantry as a “a sack of potatoes” in political terms. This is admirable, although it does draw attention to other things that Beckert declines to dwell on. He fails, for example, to consider the displacement of peasants into the urban workforce under a Soviet regime that acted in Marx’s name—and with a brutality to match any capitalist scheme of “proletarianisation”.

A similar slantedness occasionally compromises the book in its third overarching purpose—thrusting the hidden ideology of capitalism into daylight. This is a noble task, but one that requires meticulous disentangling of problems that are down to capitalism per se from those caused by, say, social inequality (which, of course, goes much further back) or even human nature. And yet there is a curious sense in which the book feels under-theorised on the question of capitalism itself.

Beckert does give a definition, of sorts, early on—capitalism is “first and foremost” about “ceaseless accumulation”, and then a bit more particularly about wealth being “principally deployed to generate more wealth”. Reading this, I found myself thinking: didn’t King Midas accumulate ceaselessly? I also wondered whether Roman merchants hawking wares round the Empire worked to a capitalist logic and, if so, when they stopped and why, and how things played out when they did. This isn’t a churlish demand for a panoramic tome of 1,325 pages to cover more ground; it’s an appeal for clarity on what we talk about when we talk about capitalism. The border of what qualifies for that name really matters for assessing the balance sheet of its crimes and its accomplishments—and for interrogating the possibilities of moving beyond it.

A number of 20th-century regimes noisily proclaimed they had achieved precisely that, and created natural experiments—such as at the border of East and West Germany or North and South Korea. It feels remiss not to pause on the unhappy results. While the book pulsates with Marxian awe at the way capitalism has reordered the planet, it shrinks from interrogating how far its efficiency relies on the same engines that power its injustices: the profit motive and private property rights. I’m not an instinctive cheerleader for either, but I didn’t close the book feeling much better armed against those who credit capitalism with rescuing a billion-plus people from extreme poverty over the last generation.

There is, for example, scant engagement with the argument that it is India’s “turn to the market” since the 1990s that has improved its stagnant living standards. The stunning achievements of Sweden’s postwar social democracy are detailed, but the question of whether its unions overreached by pushing for wage-earner funds that went beyond what was compatible with private investment is not addressed. The Chinese miracle of the last generation is vaguely attributed to a more “flexible” blend of markets and strategic planning than is seen in today’s doctrinaire west. But there are, again, few real pointers on what exactly we should keep and what we should kill from capitalism.

John Cassidy’s dazzling tour of capitalism’s intellectual horizon since the 18th century may not have quite the same breadth, but its organisation engenders more balance. A series of pen portraits of the system’s critics—some revolutionary, some reformists—draws our eyes to different iniquities. Each of the 27 substantive chapters reads like an eloquent essay in the New Yorker, where Cassidy is a staff writer.

Some names are expected, but some—the real delights—I’d scarcely encountered before. William Thompson, an unlikely scion of Ireland’s protestant ascendency, turns out to have beaten Marx to the phrase “surplus value” by decades and pre-empted the redistributive conclusions that Alfred Marshall drew from the diminishing marginal benefits of wealth by even longer. One of Thompson’s own influences, Jean Charles Léonard de Sismondi, himself anticipated Keynes by a century in warning that immiserating slumps would result under “this dangerous theory of equilibrium… automatically established”. Thompson’s friend and collaborator Anna Wheeler was just as far ahead of the game in inveighing against sex discrimination.

The variety of the critiques included is astonishing. The thought of the Luddites qualifies for a sympathetic (and Beckertian) chapter. General Ludd’s hammer was a final resort, reached for only after parliament had closed its ears to petitions to share the fruits of newfangled machinery by regulating pay. With tech bros currently telling us that there can be no stemming the digital tide that is enriching them while engulfing livelihoods in fields from retail to news, it is a timely tale.

Thomas Carlyle’s rants against Mammon and the Cash Nexus—“one of the shabbiest Gospels ever preached on Earth”—give a view of capitalism’s flaws through conservative eyes. The roots of today’s “degrowthers” are traced to the austere Romanian mathematician Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, who approached economic expansion through the prism of thermodynamics, as a “unidirectional” drift towards “irrevocable” energy waste. Silvia Federici’s agitation for wages for housework is deployed to expose not only the structural sexism of the market economy, but also the absurdities of GDP worship: when a man marries his housekeeper and stops paying her for carrying on the same tasks as his wife, her efforts do not diminish, yet the measured economy shrinks.

But where does all this lead? Certainly, racing through 250 years of sceptical thinking about capitalism, covering everything from globalisation to cultural warping, underlines how Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves have cut themselves off from every critical tradition in political economy by narrowing their mission to an indiscriminate quest for “growth”. Beyond that, however, it is a stretch to draw general lessons from Cassidy’s otherwise engrossing variety show. It is telling that the only disappointing chapter is the conclusion, which is still cramming in extra points from Joseph Stiglitz’s latest potboiler just three paragraphs from the end.

Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves have cut themselves off from every critical tradition in political economy

One big takeaway from both these books concerns how power warps thought, and how the institutions of ideas in turn entrench monied power. Beckert exposes all the Enlightenment titans who, at the height of coercive Atlantic capitalism, “sought to bury the bloody origins of their ascendent civilisations”: Kant, Voltaire, Hume and the Royal African Company investor John Locke. Later, as a more inclusive capitalism matured, he documents how the “marginal revolution” in economics achieved the “erasure of history, society, class, and power” from the discipline.

For his part, Cassidy charts the distinctly chequered course of the academic careers that shone the most unsparing light on capitalist power. Take Joan Robinson, a mind so brilliant that Keynes relied on her to kick the tyres of his General Theory prior to publication. Her judgements were sometimes wild, but her thought ran deep and wide. Robinson explained why most firms (not just monopolies) had power over prices; how big employers could control wages; and traced the roots of investment and growth back to “institutional forces, expectations, and history”—in other words, to power struggles. Cassidy mostly wears his learning lightly, but the prose gets dense as he struggles to contain Robinson within 20 pages. Her original insights, however, were no passport to the academy: she had to start out in scholarly life without either a First or a proper job.

The Polish intellectual Michał Kalecki was another great power analyst. After arriving at most of the elements of Keynesian theory before the man it would be named after, he wanted to understand why so many capitalists seemed determined to resist its practical, prosperity-boosting public interventions in the Depression. Businessmen, he concluded, feared that the taming of unemployment as “a disciplinary measure” could see them lose “control of the workplace”. Only in a state that offered substitute discipline—“the function of fascism”—would 1930s capitalists swallow proactive economic management. Keynes himself tried to get Kalecki a job, but even he couldn’t swing it.

Last but not least, the Hungarian economic historian Karl Polanyi offered a more general account of “the mutual incompatibility of Democracy and Capitalism”. A brutal “market society” was originally imposed from the top in the pre-democratic age, before a pushback from the bottom smoothed the rough edges of capitalist life. But amid the rising conflicts and trade tariffs of the interwar world, capitalists feared that their old order would vanish entirely unless democracy were snuffed out instead. Even though Polanyi’s dark ideas were playing out in many places as he developed them, he just couldn’t land a scholarly perch in England, leading to all sorts of troubles, including temporary separation from his wife.

For decades after 1945, Polanyi’s take seemed hopelessly gloomy. But, in the world being forged by Donald Trump and Elon Musk, the reconciliation of capitalism and democracy is no longer a given. We could be one big shock from the two things breaking asunder. Should that happen, for all the magic capitalism may have worked on living standards over the past 200 years, I shudder to think what horrors the next chapter in its long story could have in store.

Reviewed here

Capitalism: A Global History by Sven Beckert (Allen Lane, £50)

Capitalism and Its Critics: A Battle of Ideas in the Modern World by John Cassidy (Allen Lane, £35)