The dumbest controversy of 2025—and it is a hotly contested category—came after some remarks the film director James Gunn made about his new Superman movie. “Superman is the story of America,” he told the Sunday Times in July. “An immigrant that came from other places and populated the country…”

If you can look past Gunn’s slightly awkward spoken grammar, you’ll spot at once the word that triggered what was to follow. The I-one. Immigrant. At a time when man-babies rule the internet, and popular culture is treated as a competitive sport, having it suggested that this all-American hero isn’t actually all-American was, of course, enough to burst blood vessels. “Woke nonsense!” read one of the more temperate comments on X. “Great job leftists for making sure nobody sees this movie,” read another. “You truly are the… worst people on the earth.”

In fairness, Gunn has baited Donald Trump and his supporters in the past. And he was speaking, this time, during a summer of raids by the president’s weaponised Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency. So perhaps there is additional context for the heated response.

But, on the facts alone, the director’s comments are unimpeachable. Superman’s story, much like America’s, is unavoidably a story of immigration. Anyone who has heard of Krypton, the doomed home planet from which he was delivered as a baby, ought to know this. But if you read the most recent chronicle of the character, a huge and handsome book that earns its title of Superman: The Definitive History, the truth will hit you around the chops with all the force of a blow from the Man of Steel himself.

The Definitive History’s early pages detail the creation of Superman by two sons of Jewish immigrant families: Jerome “Jerry” Siegel, whose parents originally moved from Lithuania to New York in 1900, and Joseph “Joe” Shuster, whose own parents came from the Netherlands to Toronto. After some relocations around North America, the pair met at school in Ohio and discovered that they had much in common—not least, as Edward Gross and Robert Greenberger’s sprightly text puts it, “the fact that they were picked on by other students”.

The character they made together—after an abortive Nietzschean villain called “the Superman” in a 1933 short story written by Siegel and illustrated by Shuster—drew on their lives, experiences and fantasies. The new Superman, the proper one, would be an American who hailed from outside America and would stand against bullies on behalf of the oppressed. In his alternate persona, as the journalist Clark Kent, he would even “be meek and mild, as I was, and wear glasses, the way I do,” Siegel once admitted in an interview.

Before 18th April 1938, the world had never seen this composite being we now call the superhero

It is hard to overstate the impact of Superman’s arrival in the very first issue of DC’s Action Comics, published on 18th April 1938. The world had seen serialised heroes before then—some of whom, such as Doc Savage and John Carter of Mars, had influenced this new one—but it had never yet seen this composite being we now call the superhero. There he is on the cover, smashing a car against a rock, as criminals scatter, terrified, into the foreground. A whole new form of culture—possibly the most significant of the 20th and 21st centuries—was born in that cataclysmic moment.

Reading Action Comics #1 now, it is surprising how much of what we know about Superman is contained in its pages—or perhaps it is not, since all of the great pop-cultural icons, from Sherlock Holmes to Spider-Man, seem to appear fully formed. Superman arrives on Earth from a distant planet “destroyed by old age”. He can “hurdle a twenty-storey building… raise tremendous weights… run faster than an express train”. His costume is a blue body suit with red trunks, a red cape and a shield-like symbol across the chest. Under cover of his secret identity, he goes on a woefully unsuccessful date with Lois Lane.

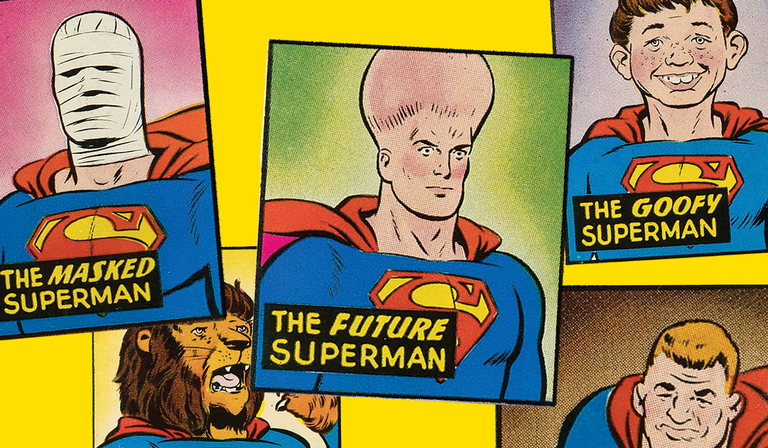

Of course, some of the details were to change: famously, Superman’s ability to leap great distances would become an ability to fly even greater ones. And, over the course of his near 90-year publishing history, new elements have been added, all tracked diligently by The Definitive History: from the name of Krypton itself (introduced in Superman #1) to his homey upbringing in rural Smallville (Superboy #2), from the nefarious Lex Luthor (Action Comics #23) to Krypto the Superdog (Adventure Comics #210).

But more important than these elements of Superman are the ethics of him. There is an ideal that he strives for—once summed up as “Truth, Justice and the American Way”, though in Gunn’s film it is turned into “the Human Way”—and that makes him political by default. Perhaps my favourite page in The Definitive History shows his two comic-book encounters with John F Kennedy, both printed after the president’s assassination. In one, JFK learns of Superman’s secret identity, though this doesn’t faze the superhero at all: “If I can’t trust the President of the United States,” he beams, “who can I trust?” You suspect an equivalent panel would not be drawn today. Trump would head straight to Truth Social to blurt about that “terrible person” and purveyor of “fake news”, Clark Kent.

This does not mean that Superman is entirely rigid. The best stories involving the character often cherry-pick from his past and choose to emphasise one quality or another—his double life as a reporter, say, or his immigrant background.

My favourite of the comic-book stories in recent years, Grant Morrison and Rags Morales’s run on Action Comics from 2011 to 2013, foregrounds the blue-collar avenger who was so prominent in Siegel and Shuster’s earliest tales. Its first issue begins with Superman rocketing into a meeting of Metropolis bigwigs who are about to uncork a bottle of champagne to celebrate a deal. “Rats with money,” he intones on landing, “and rats with guns. I’m your worst nightmare.” That issue’s cover gets its own resplendent full page in The Definitive History: it shows this younger activist Superman being shot at by the officers of the MPD; he’s wearing his cape over a T-shirt and jeans.

The character can, in fact, be taken even further. Consider Superman: Red Son—a 2003 story written by Mark Millar and illustrated by Dave Johnson and Kilian Plunkett—which crash-lands the character not in Kansas but in Soviet Ukraine, from where he grows up to be a muscular defender of “Stalin, socialism, and the international expansion of the Warsaw Pact”. Sacrilege? Not at all. Red Son is truer to its hero than most US-set tales, since it probes the questions of nature versus nurture that cling to this space-god raised (more usually) by Ma and Pa Kent. Besides, the contrast demonstrates that “Truth, Justice and the American Way” might not be all that bad, after all.

But there are limits. Turning to the pages of The Definitive History devoted to the impressive but chilly artwork for Zack Snyder’s 2013 movie Man of Steel, I felt a pang of cultural trauma. While a no-killing policy is not as intrinsic to Superman as it is to Batman, having him snap the baddie’s neck after a city-levelling punch-up—as that film did—was a bit much.

What if Superman were black? Or in the Marvel universe? Or a preening psychopath?

Many wonderful analogues, other supermen and women, have been created to explore the character beyond his natural boundaries. What if Superman were black? That’s Calvin Ellis, the US president on Earth-23 (don’t ask). What if he occupied the Marvel universe, rather than the DC one? Try Hyperion, Gladiator or the Sentry. What if he were a preening psychopath? Homelander in both the comic-book and television series The Boys. Perhaps this is the route Snyder should have taken—and spared us all in the process.

So where does this leave James Gunn’s Superman movie? From the distance of a few months, it’s clear that it gets the character—his mix of aw-shucks decency and extraterrestrial anguish—but the irony is that, for all the director’s emphasis on Supes in interviews, actor David Corenswet’s first appearance in the bodysuit was undermined by a dozen other heroes jostling for attention. Mister Terrific, Green Lantern, Hawkgirl, Metamorpho… there was a determination here to present not just the first superhero but also, seemingly, everyone he went on to inspire.

Though it is also worth noting—in view of the commenter who admonished Gunn for “making sure that nobody sees this movie”—that Superman (2025) is now the highest-grossing solo Superman film ever shown in the US, even when all the others’ box office takings are adjusted for inflation. You will, indeed, believe a man can fly. You’ll also believe a man can bellyflop on the internet.